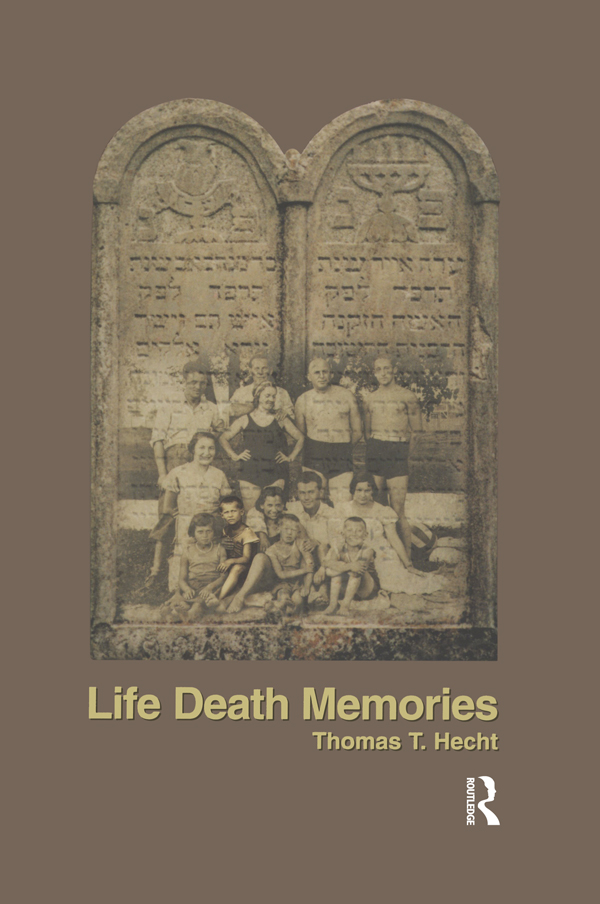

Life Death Memories

First published 2002 by Leopolis Press

Published 2019 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2002 by Thomas T. Hecht

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Card Number: 2001098087

1. Holocaust, Jewish (1939-1945), Poland

2. Memoir, Holocaust survivor

3.Poland, Busk, Ukraine, Jews, Ethnic relations

ISBN 13: 978-0-9679960-1-1 (pbk)

ISBN 13: 978-1-138-52724-9 (hbk)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this book but points out that some imperfections from the original may be apparent.

Irene Pipes

I have read and re-read Thomas T. Hechts story. To me, what is most charming about it is that he wrote it looking back into and recreating a childs perspective. Writing with love, nostalgia and sadness, he evokes so many remembered details. It took years for the survivors of the Holocaust to write their memoirs. Although there are now many of these, each one tells us new facts and presents a different point of view. Their authors bring to us different experiences, joined together in being all horrible, and show us how all suffered, whatever the family background, profession, level of income, or area of what was then Poland long ago.

Such is this story.

It is set in the town of Busk; and my connection with Busk is very dear to me, since both my paternal grand-parents, my father and all his brothers and sisters were born there. When I was four or five years old, my parents took me to visit my grandparents, who owned a large farm. My grandfather, a tall, bearded man, besides being a farmer was a very observant and learned Jew who was treated like a rabbi by his friends and neighbors. My grandmother, born Danziger, who wore a wig, was a small, quiet woman busy from morning to night with housework and feeding her large family. Our language in common was German, since they spoke Yiddish and German, and I spoke German and Polish. I remember going out on the farm and collecting a bouquet of many kinds of flowers and stalks of wheat, to take home with me. It went on top of an old, tall cabinet, awaiting the time for me to leave. To this day I remember how sorry I felt that I forgot to take it with us back to our home in Warsaw.

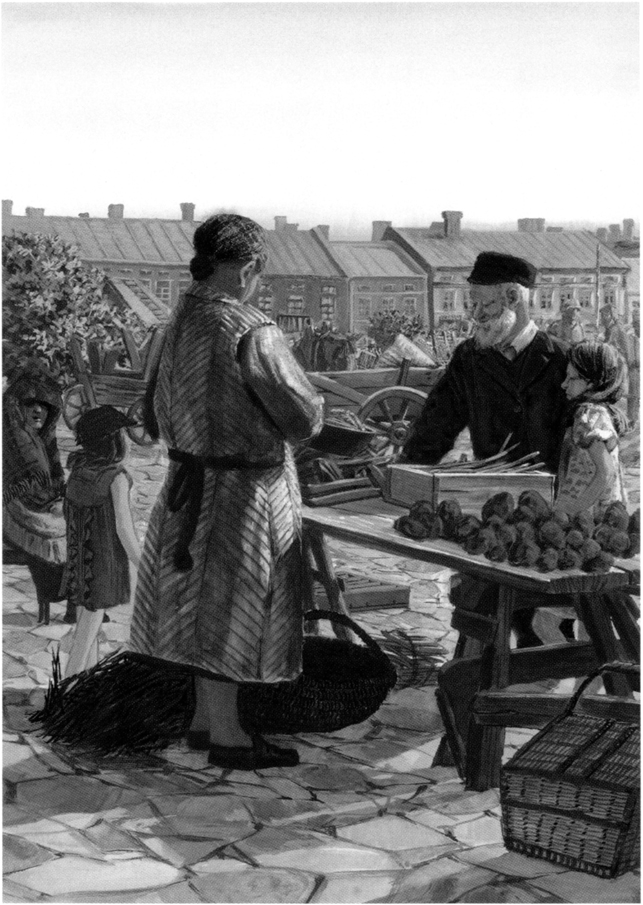

Some years ago, I interviewed one of my uncles about life in Busk; and all that Thomas Hecht describes about the village and its population of 10,000, one-third Jewish, very much agrees with what I heard from my uncle. He told me for example of the importance of Count Casimir Badeni, once the Prime Minister of Austria-Hungary, who built there a palace for himself and insisted that the railroad station be located six miles away in Krasne so that he would not be disturbed. He was friendly to the Jews and employed them on his estate.

On a trip to Poland in October 1986, I decided to visit Busk, for I was curious about my roots. This was still in the days of the Soviet Union, and travel in that region was not easy. I went by train from Krakow to Lww. The authorities could not understand why I wanted to go to Busk and presented every possible difficulty, such as that there was no car available; but after two days of argument and my agreeing to pay an exorbitant amount, I was told that a small, rickety bus, and a driver, were ready for me. I found out later that Busk was off limits to foreigners. I did ask for a driver who spoke Polish but did not get one. I was lucky anyway to have a nice, energetic young man who spoke only Ukrainian; but since the two languages are quite similar, we under stood one another. The main thing was that he under stood why I was there and what I wanted to find. The Busk of today is not the shtetl of old.

Here are some excerpts from the diary I kept of the trip:

The road to Busk is basically the road to Kiev and quite uninteresting. We passed a huge statue dedicated to 1939, the year Ukraine was liberated. At the city entrance to Busk a large statue of a woman representing good harvest greeted us. The town itself had nothing but the very basic shops and one restaurant. The houses are all of brick and cement, built since the war; the old ones were either destroyed by the Germans or taken apart by the present government to make room for new housing. We drove around and around looking for someone old enough who would remember the days before the war. We were directed to a Mrs. Dawidowska84 years oldyes, she remembered the Danziger family; they were rich; they owned the local inn; one had a barber shop and another, a farm. She suggested we find a Mr. Zielinski, a local gossip. Yes, he said, the Danzigers were all over. He climbed into our bus and took us to Sukowa Street, where the farm had been. None of the old houses was left, but at least I now know where my father was brought up.

He concluded with telling us that that the Germans rounded up 4,000 Jews from Busk and the surrounding area in the main square to be sent to death.

Irene Pipes is President of the American Association for Polish-Jewish Studies. She is married to the distiguished Russian Historian, Richard Pipes, the Frank B. Baird Jr. Professor of History, Emeritus, at Harvard University.

I may be on my way to my office, or to court, at some social event, or just at home, and my mind turns to that scene of my father and my brother during their last hours. My mind carries me back to Ulica Tarnowskiego, to the house where I was born and raised, at Tarnowskiego 9.

It is a street in Busk, formerly Poland, now Ukraine. I cannot help thinking of the street, and of when my dearest father and Lonek, my beloved brother Lonek, were passing our house on their way to the Jewish cemetery. Yes, the horse-drawn cart, and my father and Lonek inside. Was Lonek crying? And my father? Was he crying? Or were they already too frightened and exhausted to think of or to grasp the fact of death?

The cart-driver was a local man. He must have known my father. And the guards: what of their humanity? I ask myself: how, when and why did the cart-driver and the guards lose their humanity?

This event more than any other dwells indelibly in my mind and awareness. Almost to the last hours, and until it was too late, we did not believe what was happening. Yes, there were great hardships, very bad things were happening to us; and there were rumors of yet worse things happening in neighboring towns and villages. But we believed, I certainly believed, that we were special, that Busk was special, that we would come through alive.

But when not seeing the horse-drawn cart carrying my father and brother to their deaths, I can recall other images of life on my street and in my beloved little town.