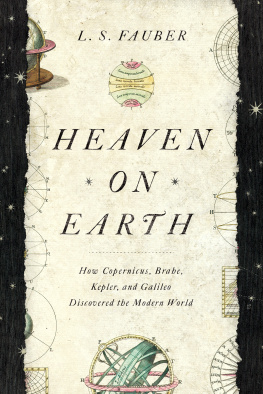

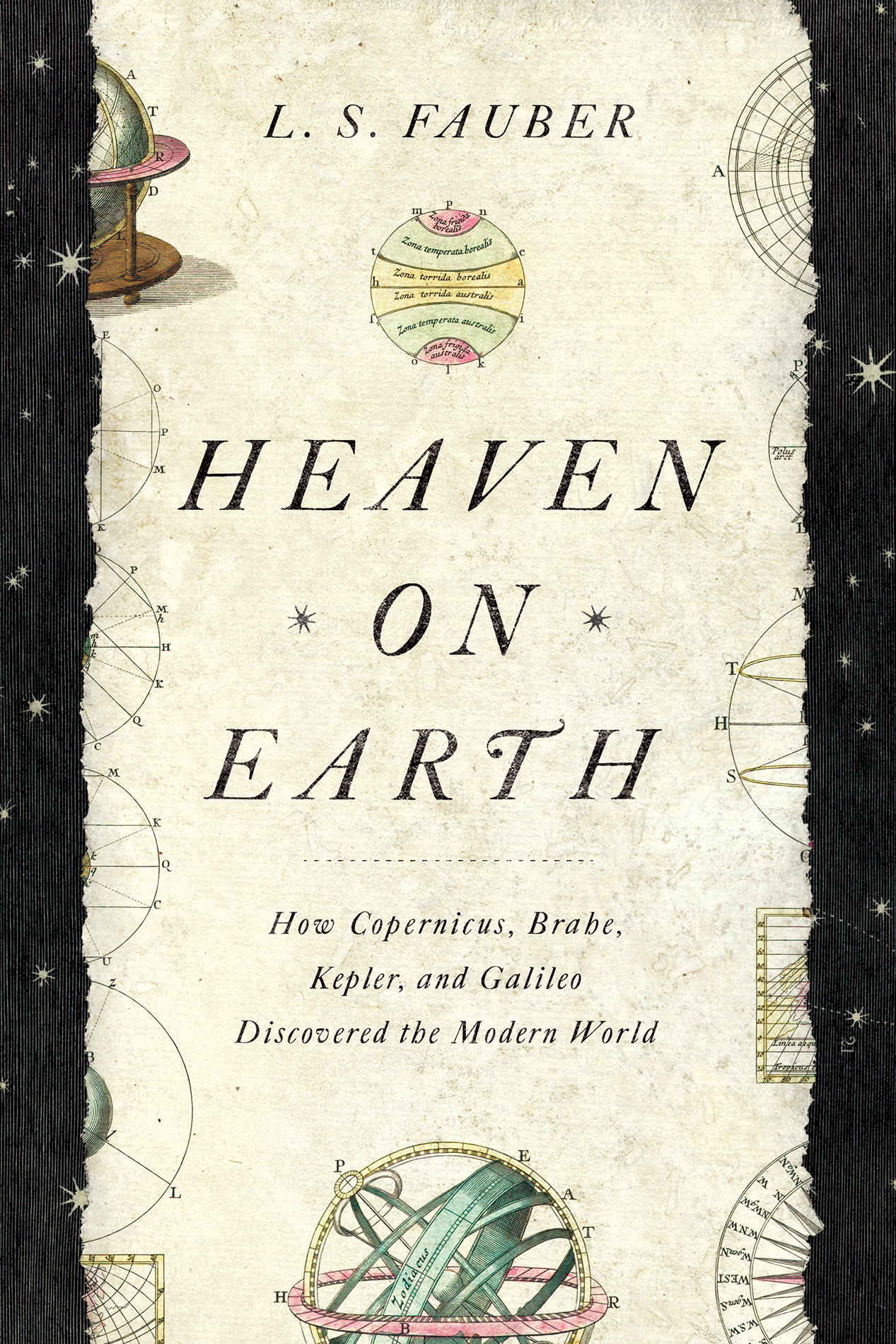

HEAVEN

ON

EARTH

HEAVEN

ON

EARTH

How Copernicus, Brahe, Kepler, and

Galileo Discovered the Modern World

L. S. FAUBER

PEGASUS BOOKS

NEW YORK LONDON

Accurate scholarship can

Unearth the whole offense

From Luther until now

That has driven a culture mad.

W. H. AUDEN,

Another Time (1939)

No mathematician is believed to be worth anything unless they have first been in trouble with the police.

JUVENAL,

Satire VI (ca. 100)

I n Europe, all throughout the sixteenth century, that dreadful era of civil strife and bloody rebellion, there lived four men who loved to watch the sky. Though they differed in nation, age, religion, and class, they were all united by a single discovery, a wondrous discovery, a truly unbelievable discovery that became the herald of every other social change within their violent, paranoid era. This discovery pushed the spirits of all four men together with such force that, even when separated by the chasms of time and space, they became, to one another, fathers, brothers, and sons. When they made contact, in books, letters, or person, it was with all the possible intimacy of long-lost relatives. They offered one another the same much-needed community they learned from their siblings, parents, children, and wives. Like most families, there was much love between them, but also much error. Like all families, their drama was too immense for a single life to contain.

In the following pages, I tell the story of this drama, from its genesis as a passing daydream in the head of a little Polish boy all the way up to the grand world stage, in the trial of the century, awaiting judgment before the greatest political power of its day. The characters of this drama are now so famous they may each be introduced with only one name: Copernicus, Tycho, Kepler, and Galileo discovered the modern Earth, a moving Earth, and in so doing, discovered the uneasy conditions of modern life itself. Theirs is not only a story of individual genius. To tell such a story would not be a lie, but a withholding of other, more essential truths. Theirs is an intergenerational epic, a family saga, of the most unusual sort.

A life, in which a boy stumbles into manhood

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

| Lucas Watzenrode | his uncle & Prince-Bishop |

| George Joachim Rheticus | his acolyte & friend |

| Tiedemann Giese | his dear friend & fellow canon |

| Andreas Osiander | Lutheran minster & |

| dilettante stargazer |

| Domenico Maria da Novara | his favorite teacher |

| Erasmus Reinhold | his second acolyte |

| Martin Luther | reformer of legend |

| The Teutonic Knights | a war-making crew |

| The Popes | whose passings keep the time |

| as the second hand of a clock |

MAJOR WORKS

Little Commentary First Account On The Revolutions

YEARS ENCOMPASSED

14911551

W hen Nicolaus Kopernigk was a gangling, unattractive teenager, with no lofty ambitions, he did not mean to trouble anybody. He liked math. He was quiet. He did not like to cut his hair.

In the fall of 1491, he was packing his bags, preparing for a sobering departure from his childhood home in Torun. Within his mind lay the seed of a troubling idea concerning his favorite subject, astronomy, and the possible movement of the Earth. Such a seed had not yet had any time to grow, but he was, at that moment, readying himself for college, one of the rare places in medieval Europe where an intellect could flourish. He did not look impressive. He looked rather silly, if his portraits are any guide, with a tiny mouth inherited from his mothers side of the family and big white rings around his eyes, which made the whole rest of his face seem dirty. So unremarkable was he that no one made any note of his leaving for a two days ride south through the Polish countryside to begin his adult years at the University of Krakow.

Time makes strangers of us more than distance ever could. The world Nicolaus journeyed through was an old one: small, wild, and weird. There were no narrow buildings. There were no giant cities. There were no factories coughing smoke into the air. There was no place named America, no light bulbs, no vaccines, no nationalism, no cheap steel, no secular state, no accurate clocks, no feminism, barely any guns, virtually no coffee, absolutely no democracy, and almost no books. A healthy town would, at least, have a new mechanized corn mill to serve its citizens, outside which urchins, lepers, and women of ill repute would loiter in the shade; here was the first hint of modernity rising.

Traveling near the fertile Vistula River, the boy saw enough sprung-up shanty villages to form a sorry picture of his old world. Most people were peasants, and most peasants were dirt poor. They had almost nothing, he observed: a single cow, a lonely pig, one she-goat, a sack of grain, all providing a meager diet of homemade cheese and black bread. From this pittance, food-rent, worth one day of work a week, went straight into the thankless bellies of the noble elite. Sometimes a farming man, usually one inspirited by a lusty new bride, got it into his head to run away in quest of a better life; such couples always returned dejected, within six months, punished by reassignment onto untilled, hardscrabble land. They had nothing better.

The poverty of their condition brought many to the point of rebellion, especially in countries more distant from Rome, seat of the Catholic Church, the organizing principle of medieval Europe. Excepting a handful of Jews demanded by authorities for their necessary sin of banking, every European was Catholic by default; every poor little town had built a poor little church of stone, standing room only, with no stained glass in the windows. There the common folk crowded in. For them, this church was not only a religious institution but the means by which they understood themselves as social beings. God was in the audience of their every public ceremony, from the sacrament of marriage to the coronation of kings to the baptism of children to the divine appointment of clergymen, who comforted them every Sunday with words from the wonderful Bible. The Church soothed the peasant spirit and led many through an honest, peaceful, happy life of religious devotion.

In the poor country, a parish was lucky to get a priest who could read and write, but ideally, a clergyman was the locus of wisdom in the Catholic community, entrusted with knowledge, which confused and complicated the mores of simple faith. Nicolaus was already skilled in Latin, and those close to him were expecting his college venture to result in a successful career with the Church. At the age of eighteen, he was already full of knowledge denied to common people.

Pythagoras, he knew, was the first ancient to propose that mathematics was the key to understanding nature. This idea had so excited the Greek mystic that he had even started a pagan cult about it. This cult told all its members to never eat beans, and supposedly drowned a man for proving that the square root of two was not a fraction, so people naturally started to assume that they were a bit crazy. But their doctrine that math could be used to understand nature turned out to be pretty sane. After them came Plato and Platos student Aristotle, whose surviving works span every genre and were read by every serious student of Latin and Greek. Aristotles philosophies had become so hopelessly interwoven with medieval biblical interpretation that only the sort of extensive study Nicolaus made could distinguish the two. Aristotle had divided the world into physics, the study of change, and metaphysics, the study of the unchanging, just as the Church served as the holy intermediary between the material world and their transcendent deity. Aristotle had even referred to metaphysics as theology. Physics concerned life here on Earth, he said, which was dirty and smelly and rotten, while metaphysics involved things above the Moon, which were perfect. While these things above the Moon may move, their movements were not subject to change; they moved in ways predetermined by a first mover. The Greeks called this first mover Logos, Reason, the Divine Word, but all good Catholics called it God.

Next page