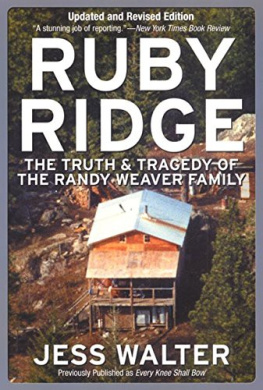

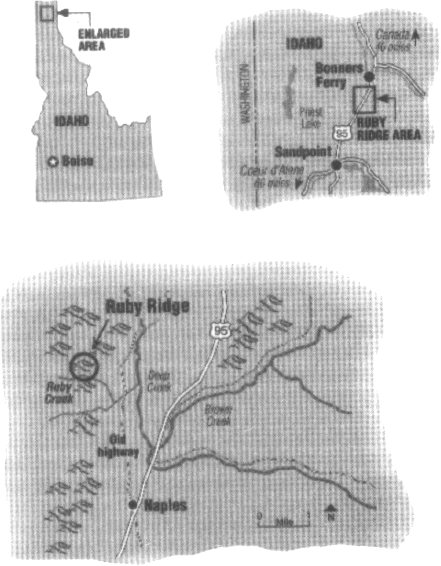

R UBY CREEK IS A STONE-BEDDED scratch along the base of a rocky knob called Ruby Ridge, in that part of North Idaho aimed like a rifle barrel at Canada, the part of Idaho known as the Panhandle. The ridge isnt much different from the mountains around it. No Trespassing signs are nailed to the trees, in whose gaps flicker the suggestion of cabins and trailers, connected by driveways that disappear into the woods like smoke. Beneath Ruby Ridge, one unsure lane leaves the old highway. A road at first, it crosses the dark creek and becomes a narrow swipe of dirt, switching back every few hundred feet along imposing root-veined banks. The path climbs easily for a couple of miles until it becomes nothing more than two tracks, which cut through a mile of woods so dense they choke off the midday sun. Take the right fork and the path breaks through the forest into a brief meadow and opens to a steep, wooded field that climbs impossibly and spills out finally on a rock-strewn knob with a predawn view of everything: a 120-degree, 40-mile window on Idaho, Montana, and Canada. On this point, 3,100 feet above sea level, the sky is close and cloudless. The sun bakes the forest floor and the crowns of ponderosa pines until nightfall, when the tired heat slips away and the deep chill of granite bedrock refills the forest. Cold gusts run like liquid off these wooded peaks, merging into wind-whipped rivers of air that can tip the plume from a cabin woodstove and defy common sense by dragging smoke downhill.

On this point nine years ago stood a simple cabin, a ramshackle construction of weathered plywood, sawmill waste, and two-by-fours, wedged into the hillside among an outcrop of boulders. Hinged windows were set into the cabin walls seemingly at random, like afterthoughts. A stovepipe chimney rose from the peak of a corrugated steel roof, which was rusted in places and dipped at the corners. There was no electricity up here. No phone. You could survey forever and not find a piece of ground flat enough for a home on this ridge, and so the cabin was built on stilts like the legs of a sitting doglonger in front to reach out over the shoulder of this cliff and level the house. There was a scattering of outbuildings, too, including a birthing sheda guest house built like a tiny barn, used by the religious mother of this family as a retreat when she was menstruating, when she believed she was unclean.

That woman has been dead for years. Her family has moved away and their cabin is gone. The yard has grown over and the point is empty. Standing alone on this craggy bluff in thick Idaho forest, it is difficult to imagine how important this place has become, to conjure the events that took place here: the frightened prophecies, gunfire, and death; the Green Berets, FBI snipers, and angry skinheads; the trial, lawsuits, and congressional hearings, the horrible legacies of Waco and Oklahoma City. When images do come, they are twisted and tragicas perplexing as your first view of smoke racing downhill.

R ANDY WEAVER WAS A THIN , hollow-eyed woodcutter who decided one summer to drive down from his cabin to a summer meeting of the Aryan Nationsan organization whose followers believe Jews are the children of Satan and that white America should have its own homeland.

The seventy-mile drive forever changed his life. Weaver and his family, in turn, unwittingly changed the way many Americans view their freedoms, their values, and their government. The Weavers road led to an Old West gunfight, three deaths, and the invasion of a remote county in North Idaho by an army of state and federal agents. It channeled Americas deepest insecurities and drew thousands of people into a whorl of fear and stubbornness, mistakes and misjudgments, lies and a cover-up that continues to shake the top levels of the FBI.

The same road cuts through Waco, Texas, where in 1993, seventy-nine peopleincluding twenty-two childrenwere killed in a gunfight and standoff between federal agents and the Branch Davidian religious sect.

Those two placesWaco and Ruby Ridgewere forever linked on April 19, 1995, when a bomb tore in half the federal building in Oklahoma City, killing 168 people, 19 of them children. Before he was put to death, a disillusioned Gulf War veteran named Timothy McVeigh said he planted the bomb to avenge the deaths at Waco and Ruby Ridge. In the 2001 book American Terrorist, McVeigh told authors Lou Michel and Dan Herbeck that he did it for the larger good.

How could a minor weapons case involving an itinerant woodcutter in the middle of nowhere spark a chain of events that would eventually lead to the worst domestic terrorist attack in American history?

During the 1993 trial of Randy Weaver and his friend Kevin Harris, the brilliantly bombastic lawyer Gerry Spence argued that America needs people like Randy and Vicki Weaver to show us the line where our freedoms begin and end. In the Weaver case, that line fades in and out and switches back dizzyingly, like the old logging road that leads away from the top of Ruby Ridge.

I N THE NINE YEARS since the standoff at Ruby Ridge and in the six years since this book first appeared, much has happened. Yet little has changed. Tens of millions of dollars have been spent on hearings and investigations that failed to resolve the most basic questions about the standoff. Almost $3.5 million was paid out in settlements that settled nothing.

Nine years later, the courts are still flip-flopping over whether a federal agent should be tried for his actions at Ruby Ridge. Investigators, lawyers, and federal officers are still debating who shot first. Top FBI officials are still denying that they approved the bureaus unprecedented and illegal orders to shoot civilians without provocation.

Nine years later, the sniper who killed Vicki Weaver still works for the FBI.

The case continues to hum on Internet Web sites and scream from right-wing newspapers. The words Ruby Ridge are fixed at the bottom of every news story about the ten-year crisis of confidence and competence in the FBI. And every time a person holes up in a ramshackle house, every time a suspect refuses to come out, every time a person accuses the government of going too far, someone is likely to say, We dont want this to become another Ruby Ridge.

The Weaver case gave a name to that sometimes dangerous space between people and their government. It brought paranoia into the mainstream. For how can you convince people that their government isnt out to get them when, on Ruby Ridge, the FBI gave itself permission to shoot its own citizens? How can you tell people to trust a government that covered up details of the case and assigned agents to investigate themselves?

There is little wonder that for many it has become a symbol for government tyranny.

But symbols are nothing more than half-truths and they fall short of explaining a place as hard and remote as Ruby Ridge. From this jagged point, the Weaver case is not proof of broad government oppression and tyranny, but of human fallibility and inhuman bureaucracy, of competitive law enforcement agencies and blind stubbornness. The Randy Weaver case is a stop sign, a warningnot of the dangers of right-wing conspiracies or of government conspiraciesbut of the danger of conspiracy thinking itself, by people and by governments.