Contents

Geoffrey Wansell

PURE EVIL

Inside the Minds and Crimes of Britains Worst Criminals

For my son Dan Wansell and myeditor Dan Bunyard

PENGUIN BOOKS

PURE EVIL

Geoffrey Wansell has observed criminals with whole-life sentences, often up close and very personal, for over twenty years. In this chilling yet fascinating book, he looks for answers, and in the process reveals shocking insights into the foulest crimes known to mankind.

Preface: DeathsShadow

This is a book about murder, and the menand women who commit the foulest crime known to mankind. But it is also a book aboutthe ultimate penalty those killers face under English law a whole lifesentence of imprisonment, which means they must spend the rest of their naturallives behind bars with only the remotest possibility of release.

It also asks a question doeslocking the worst of the worst offenders up forever and throwing away the keyrepresent the right response from society? Indeed, do we as a society trulyunderstand the consequences of a whole life sentence?

Are we comfortable, for example, insending a young man in his early twenties to jail for the next sixty, or evenseventy years of what remains of his life? Are we so determined on revenge for thevictims and punishment for the offender that we can sentence a young woman in herearly thirties to spend the rest of her life behind bars?

One lifer himself once memorably said,What keeps me going is knowing Ill be dead soon enough anyway ofnatural causes. The average male only lives until hes sixty to sixty-five.The way I see it, Im closer to death than birth.

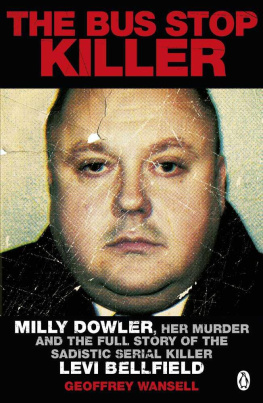

As an author who has written two booksabout individuals sentenced to spend the rest of their lives in a cell theGloucester serial killer Rosemary West and the bus stop killer Levi Bellfield I wanted to try and find an answer to that question, and others. Did Ithink, for example, that either of those killers should ever qualify forrelease?

That is an importantquestion as we no longer have the death penalty in this country. It disappeared in1965 fifty years ago last year and I have no quarrel with that. Thepossibility that any man or woman should have their life taken away by the statewhen there is even the remotest possibility that there could have been a miscarriageof justice has always seemed to me an unanswerable argument against the deathpenalty. No civilised society should ever allow for the possibility that it can sendan innocent man or woman to the gallows.

The most severe penalty that anymurderer in this country can now receive, therefore, is a whole life sentence, andthere are more than fifty people currently serving that sentence today, two of whomare women, the rest men. Indeed there are now more prisoners serving whole lifesentences than at any time in our history, and the number has more than doubled inthe past fifteen years.

How did that come about? In 1965, inplace of the death penalty came a mandatory life sentence for all murderconvictions, on the understanding that every convicted killer theoreticallyforfeited his liberty to the state forever. In practice, however, nearly all lifersin the twenty years after 1965 were released on licence at some point, when theywere deemed to no longer present a risk to society. The average lifesentence at that time was around ten years, which aroused increasing public concernas the years passed, in part encouraged by the controversy over the YorkshireRippers sentence in 1981.

That concern eventually provoked apolitical reaction, and in 1983 the then Conservative Home Secretary, the late LeonBrittan, began to set minimum terms that certain convicted killers were compelled toserve behind bars before they could be considered for release on licence. He alsogave any future Home Secretary the power to keep a killerimprisoned beyond the recommended term, as was the case for the Moors Murderer MyraHindley. In 1985 Brittan imposed a thirty year minimum upon her that meant sheshould remain in prison until at least 1995 thirty years after her originalarrest.

In 1989, however, the Conservative HomeSecretary David Waddington imposed a whole life tariff on Hindley, after sheconfessed to having been more involved in the murders than she had previouslyadmitted. Hindley was then persistently denied release by succeeding HomeSecretaries and was kept in prison far beyond the thirty-year term she had beenallocated. In fact Hindley remained a prisoner until her death on 15 November 2002at the age of sixty having spent thirty-seven years of her life behindbars.

In May 2002 the European Court of HumanRights ruled that the decisions about sentencing made by the Home Secretary were anabuse of power, and that the responsibility for deciding the length of sentenceshould be transferred from politicians to the judiciary. The then Labour HomeSecretary David Blunkett accepted the ruling, but insisted on providing a new set ofmandatory guidelines to judges about how long offenders who committed the mostheinous crimes should serve under his new Criminal Justice Act, passed in 2003.

In particular, Blunkettsguidelines suggested, where an offender was twenty-one or over at the time of theoffence and the Court took the view that the murder committed was so grave that itdemanded the most severe penalty he or she should spend the rest of theirlife in prison on a whole life order that was theappropriate starting point.

Those grave cases were defined asincluding: the murder of two or more persons where each murder involved a substantial degree of premeditation, the abduction of thevictim, or sexual or sadistic conduct; the murder of a child if it involved theabduction of the child or sexual or sadistic motivation; a murder done for thepurpose of advancing a political, religious or ideological cause; and the murder byan offender previously convicted of murder.

Over the past twelve years thoseguidelines have been subtly amended to allow judges increasing leeway to pass awhole life sentence if they feel the murder is particularly heinous, even if it doesnot exactly satisfy those definitions.

Gradually, however, this has led toambiguity about what exactly constitutes a sufficiently heinous crime to demand awhole life sentence. In the case of the brutal massacre of Fusilier Lee Rigby inWoolwich, London in May 2013, for example, one of his very public attackers wasgiven a whole life sentence while the other was not, even though both were convictedby the jury of the same murder.

Yet after a dozen years of leavingsentencing powers in the hands of the judiciary, there are still underlying moralquestions that remain unanswered. Do we take the draconian action of denying akiller freedom forever just to satisfy the demand for punishment and revenge on theoffender from the families of the victims? Or does the general public demand it?Intriguingly, England and Holland are the only countries in Europe that still have awhole life sentence for the most heinous murders the judiciary in Scotlanddecided on a fixed term when a life sentence was imposed in 2001, after which theoffender had at least to be considered for release.

I wanted to look at the killers and themurders they committed, as well as at the reactions of the victims families,the police who investigated the crimes and the judges who sentenced the offenders,to see if I could discern a pattern.