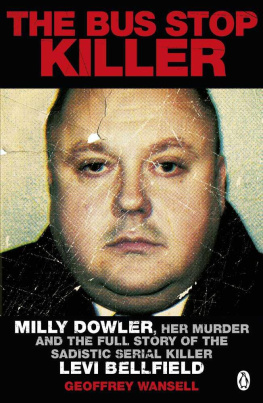

GEOFFREY WANSELL is a writer and producer, whose best-selling biographies include the Gloucester murderer Frederick West, the controversial tycoon and financier Sir James Goldsmith and the Hollywood legend Cary Grant. Still working as a journalist, for the Daily Mail, his columns and articles have appeared in almost every important British and American newspaper and magazine, and his work has been syndicated around the world. He was also the executive producer of the Twentieth Century Fox feature film When the Whales Came, starring Paul Scofield and Helen Mirren, which was shown in more than thirty countries around the world. Born in Scotland, he lives in London.

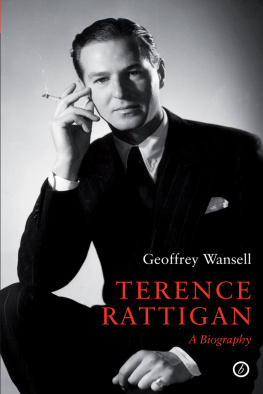

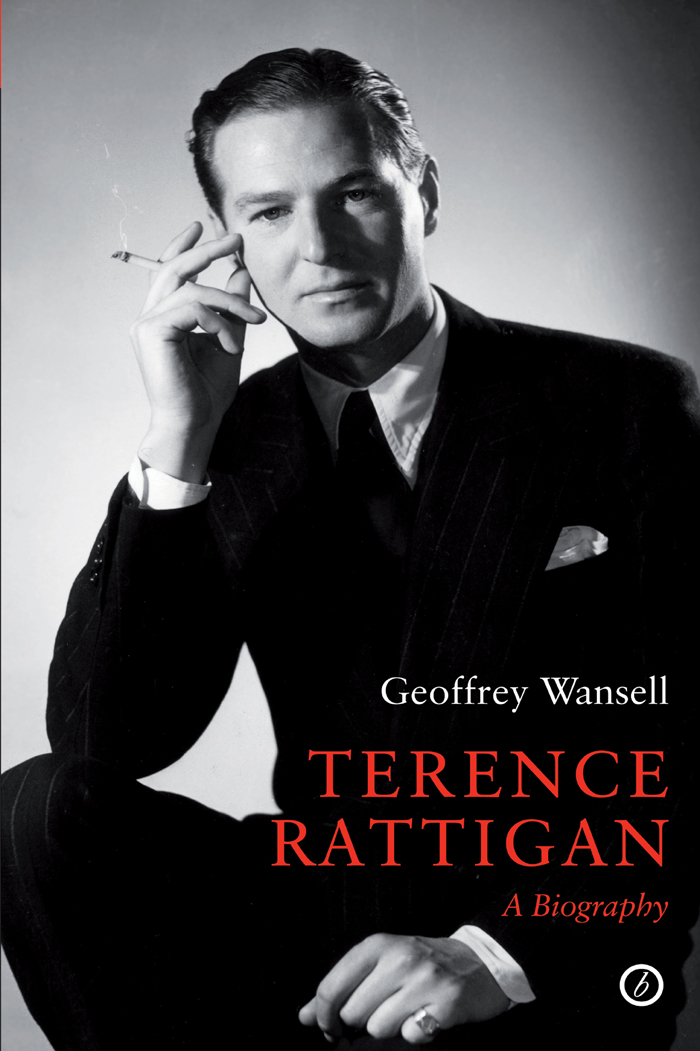

TERENCE RATTIGAN

by Geoffrey Wansell

OBERON BOOKS

LONDON

First published in 1995 by Fourth Estate Ltd

First published in paperback in 2009 by Oberon Books Ltd

Electronic edition published in 2012

Oberon Books Ltd

521 Caledonian Road, London N7 9RH

Tel: 020 7607 3637 / Fax: 020 7607 3629

e-mail:

website: www.oberonbooks.com

Copyright Geoffrey Wansell 1995, 2009

Geoffrey Wansell is hereby identified as author of this work in accordance with section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. The author has asserted his moral rights.

You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or binding or by any means (print, electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Every attempt has been made to trace the copyright holders of the photographs reprinted in this book. Acknowledgement is made in all cases where the source is available.

PB ISBN 978-1-84002-838-6

EPUB ISBN 978-1-84943-267-2

Cover photograph of Terence Rattigan by Gordon Anthony, 1946 (Getty Images)

Visit www.oberonbooks.com to read more about all our books and to buy them. You will also find features, author interviews and news of any author events, and you can sign up for e-newsletters so that you're always first to hear about our new releases.

Printed, bound and converted in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd., Croydon, CR0 4YY.

PREFACE

Why does anyone write a biography? Does the biographer see himself in his subject? Is there some hidden chord struck that leads the one to the other? I am not sure, but I do know that my father looked astonishingly like Terence Rattigan. They shared the same sleek short haircut, just as they both invariably wore a collar and tie. They were also born within a few years of each other, on either side of the Great War. Indeed both Rattigan and my father were Londoners, though my father was unmistakably a cockney from Islington, while Rattigan was just as unmistakably a toff from Kensington.

Terence Rattigan and my father shared a common heritage, and culture, even though they were forever separated, both by the divides of the English class system and by success. By the time my father had become a serious young theatregoer of eighteen, Rattigan, at twenty-five, was already established as the West End's brightest new playwright, the author of London's latest comedy sensation, French Without Tears. But the divide between them did nothing to lessen my father's admiration for his slightly older contemporary. Throughout his life, my father loved the plays of Terence Rattigan almost as much as he loved the theatre itself.

It was a love that he passed on to me. Almost my first memory as a child was of being taken to the pantomime Mother Goose at the Finsbury Park Empire, much as Rattigan's was of being taken to see Cinderella. By the time I was ten, I had been inside almost every London theatre, though more often in the upper circle than the stalls. But by then, the summer of 1955, the London theatre was on the brink of a cataclysmic change.

Look Back in Anger opened in London in May 1956, two months before my eleventh birthday, and inevitably I became a child of the Osborne generation, weaned at the Royal Court, on the Observer reviews of Kenneth Tynan, and on a diet of Arnold Wesker, Joan Littlewood and Harold Pinter. For his part, my father loathed the new angry young men. He remained unrepentantly a member of the Rattigan generation, fervent in his admiration for The Deep Blue Sea, The Browning Version and Separate Tables. And we argued incessantly as a result. I was convinced that the world of drawing-rooms and French windows, of elegant dresses and gentlemen in dinner jackets, was doomed. My father was equally convinced that thekitchen sink would eventually disappear down its own plughole; and that, in any case, it did not hold a candle to Rattigan.

For a long time it seemed that I was right. Terence Rattigan was consigned to the footnotes of British drama, while Osborne, Pinter and Tynan held the stage. Tragically, by the time I began to realise that perhaps I had been too hasty, too anxious to follow the theatrical fashion, it was too late. My father was dead. He died so suddenly in the summer of 1985 that I never had the opportunity to put it to him that perhaps we had both been right. Osborne and Pinter were good, but so too was Rattigan, and a great deal better than I had ever been prepared to accept.

More than any other, then, my father is the reason I chose to write a book about Terence Rattigan. But it was not simply the memories of our violent arguments that spurred me on. There was another reason. Because my father was a child of Rattigan's generation, so he too shared the publicly stiff upper lip, the steadfastly cautious public persona. Like Rattigan, my father chose to hide himself away in a pinstripe suit. For their generation of Englishmen, emotion was always kept strictly under control. To talk about emotions, even worse to reveal them, was not my father's way. That too he shared with Rattigan.

In particular, my father was sensitive about any discussion of sexuality. And when it came to homosexuality, my father, my mother, and indeed most other people I knew in postwar Britain, were adamantly of the same mind. To them homosexuality was a repellent, disgusting deviation, not to be tolerated at any price; a threat to society and to the young, which no right-thinking person could possibly tolerate or condone. It was truly the love that dared not speak its name. If that now seems hardly credible, indeed itself almost repellent, let me illustrate my point with another personal experience.

When I was a small boy still discovering Enid Blyton and Richmal Crompton in the local library, one of the librarians was particularly kind to me. He gradually became a friend of the family, dropping in on Saturdays after the library closed, or when it was half-day closing. My mother liked him, though my father did not meet him all that often. One Saturday, the librarian did not appear. He was missing on Wednesday as well, and the following Saturday. Finally, my mother struggled to tell me, through agonies of embarrassment, that he had been arrested in a public lavatory at Arnos Grove underground station for indecency. Though I had no idea at all what that meant, my parents decided that they, and I, should neversee him again. The librarian in question had never made the slightest step towards seduction, but even the possibility that he might have done so was too much for my parents. An exposed homosexual, particularly one who had been arrested for cottaging, was not a person to be invited into the house.