About the Book

I needed to get to the stopping places, so I needed to get on the road. It was the road where I might at last find out where I belonged.

Damian Le Bas grew up surrounded by Gypsy history. His great-grandmother would tell him stories of her childhood in the ancient Romani language; the places her family stopped and worked, the ways they lived, the superstitions and lore of their people. But his own experience of life on the road was limited to Ford Transit journeys from West Sussex to Hampshire to sell flowers.

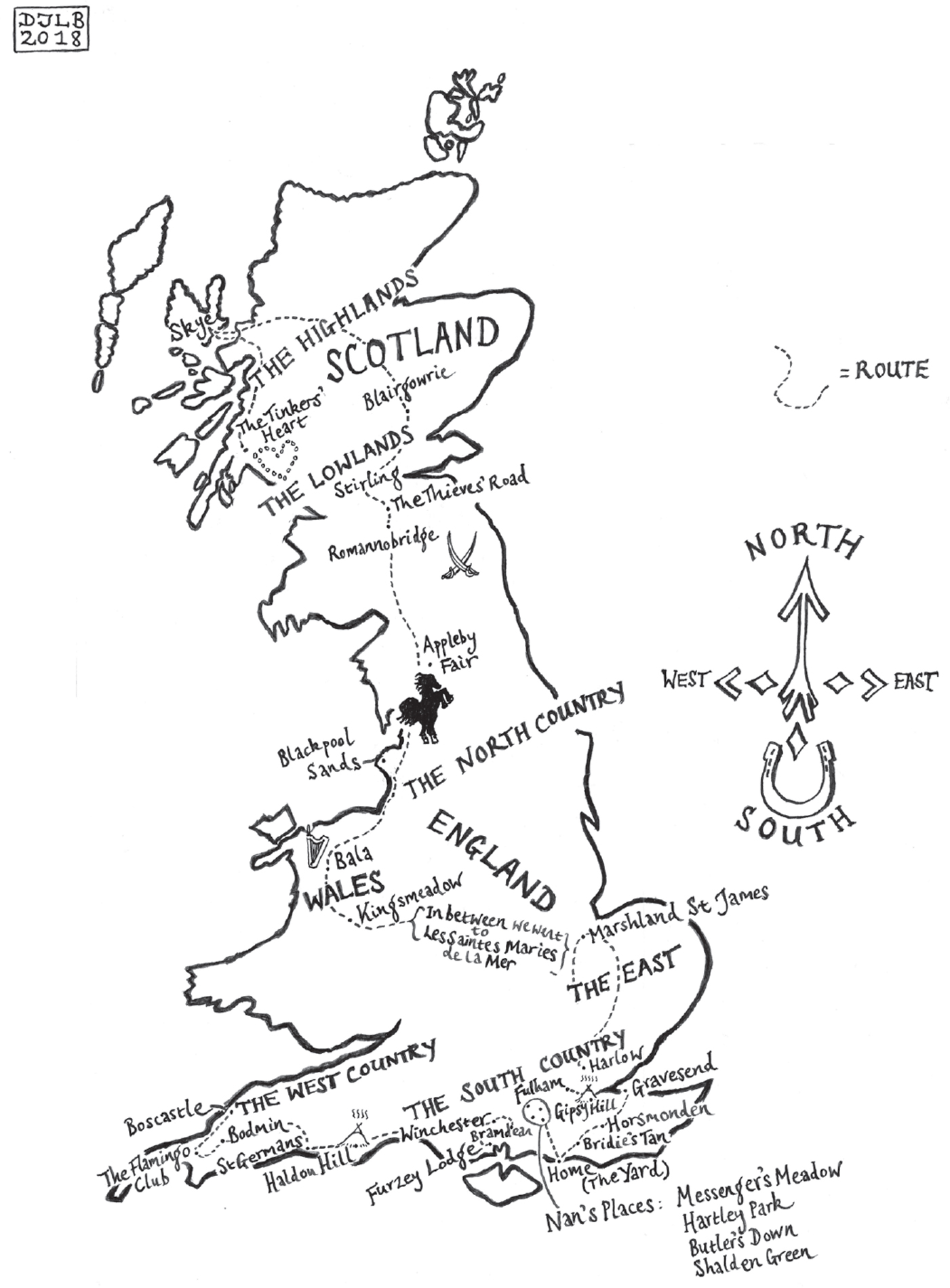

In a bid to understand his Gypsy heritage, the history of the Britains Romanies and the rhythms of their life today, Damian sets out on a journey to discover the atchin tans, or stopping places the old encampment sites known only to Travellers. Through winter frosts and summer dawns, from horse fairs to Gypsy churches, neon-lit lay-bys to fern-covered banks, Damian lives on the road, somewhere between the romanticised Gypsies of old, and their much-maligned descendants of today.

In this powerful and soulful debut, Damian le Bas brings the places, characters and stories of his to bold and vigorous life.

About the Author

Damian Le Bas was born in 1985 to a long line of Gypsies and Travellers. He was raised within a network of relations who taught him how to ride and drive ponies, tractors and trucks, sing melancholy cowboy ballads and speak the thousand-year-old Romani tongue. He was awarded scholarships to study at Christs Hospital and the University of Oxford. Between 2011 and 2015 he was the editor of Travellers Times, Britains only national magazine for Gypsies and Travellers. The Stopping Places is his first book.

Damian lives and works mostly in Kent, with his wife (the actor Candis Nergaard); and Sussex, where he grew up and where his nan who taught him the old Romany Travellers little-known routes and ways still lives.

In memory of my dad Damian John Le Bas 19632017

There is a road that runs from the salt coast of Sussex, back to the green hop gardens of rural Hampshire. It is an old road, a road of black and white; a road composed of many roads. Some of them have half-memorable names: the Valley, the Long Furlong, and Harting Down, a hill of many stags. Most have no name but a faceless coda of letter and number: the A27 westbound, the A286 out of Chichester, the B2141 from Mid Lavant to Harting. But in me all these disparate roads add up to just one: the road from the world I grew up in, to the world of wagons and tents that passed in the decades before I was born.

It was a road we took twice a week throughout my childhood, from the yard where we lived to a cobbled old market town called Petersfield. We had a pitch there a spot on the main square where four generations of my family would take turns to stand out in all seasons and sell bunches of flowers. We made the journey in a growling old white Ford Transit van, lined with rattling plywood and heavily laden with flowers. There were boxes of daffodils packed squeaky tight; tall green buckets of chrysanthemums, yellow and copper and pink; stargazer lilies that burst into purple and white streaked with orange. There were little black buckets of freesias, their buds like fruit humbug sweets sucked to a tiny, bright core. Spray carnations, the white ones frill-edged with light red, yellow ones tinged with peach. Ferns in dark greens jostled against the million tiny white stars of gypsophila.

In one corner of the van were stashed the less interesting tools of the trade: cellophane, secateurs, reams of tissue-thin wrapping paper in pale pastel shades, and boxes of tape and elastic bands to hold all our arrangements together. And I learned the jargon and abbreviations of the trade the long, plummy, tongue-twister names of flowers truncated to working-class forms: spray cars, daffs, sprig of gyp, pinks, chrysants and stocks. And occasionally wed use our own words when we didnt want customers listening: Kekker, theyre dui bar a go. Atch on, the mollishas dinlo. Kur the vonger in your putsel. Dordi chavi, mingries akai. I had no idea where these words came from, or why we understood them and almost nobody else did. But Id learned not to use them at school. If I did, a long silence would follow, turning my mood from light to dark, and I would feel lonelier once the silence had passed.

I had already been making this journey for years before I began to think about how it had started. Of course, we went to Petersfield to sell flowers, but why there? Why this twice-weekly trip, an hour each way, to a little town miles from where we lived? Why didnt we just sell flowers closer to home? We had smaller pitches in other towns, too, dotted around the vicinity: Lancing, Broadwater, Emsworth, Godalming, Selsey. A roll call of places that no one outside the region had heard of. But there was something special about Petersfield. I could tell that my elders all felt it; they looked forward to going there more; there was anticipation each evening before we set off.

On the way, my elders would point and nod at empty spaces by the sides of the road, flat areas on verges and slightly raised banks, vacant pull-ins and lay-bys, and make comments as if things were there, things that I couldnt see. The references were muttered and coded, their significance unclear to a childs ears, but they stood out against the rest of the conversation like a broken trail of breadcrumbs in the mud of the woods. That was where Uncle and they used to stop, look. I can still see me granny sat there. Cousins lay-by, look, Dee. I tried hard to tune in to the meaning, but never felt brave enough to ask what these phrases meant. They were glimmers of another world, but it felt as distant as the stars. I knew the places they were pointing out had something to do with the time they were on the road most of my family were settled now, living in houses or caravans and mobile homes on private bits of land. But in spite of my interest, I wouldnt ask questions. Twin dictums ruled over my childhood, austere morals that had survived the transition from nomadic to settled life, remnants of a less indulgent, almost bygone time. One was a saying Ive heard many people use: Children should be seen and not heard. Another was specific to my family and their relations, and was drummed into me as the only right way for a child to behave when in company: Keep your eyes and ears open, and your mouth shut. And while I was a young boy, when it came to this half-secret world, that was just what I did.

Alongside selling flowers, the family had roofing and car-breaking businesses. We had a big field and a yard, a word that seemed to mean a place where all things might, and did, happen. Terriers, geese and perturbed-looking cockerels roamed in between the legs of cantankerous horses. Stables were stacked full of the musty paraphernalia of horsemanship, flower-selling, roofing and car respraying. Bits of cars lay everywhere, named as if they were the parts or clothes of people or animals: bonnets, boots, seats, wings, belts. There were brass-handled horsewhips, jangling harnesses, buckets of molasses-sprayed chaff and milled sugar-beet, bales of sweet-smelling fresh hay. But all of this old rustic stuff was stacked and wedged in amongst the hard and greasy gear of the family economy: gas bottles, blowtorches, leaky old engines, spray paint, rolls of lead, felt, and seemingly infinite stacks of every conceivable type of roof tile. A heavy boxing bag swung with barely perceptible creaks, keeping time in the half-light of the dusty old garage.