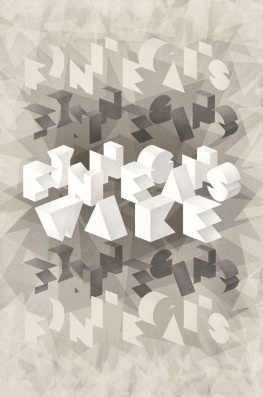

IMPOSSIBLE JOYCE

Impossible Joyce

Finnegans Wakes

PATRICK ONEILL

University of Toronto Press 2013

Toronto Buffalo London

www.utppublishing.com

Printed in Canada

ISBN 978-1-4426-4643-8 (cloth)

Printed on acid-free, 100% post-consumer recycled paper with vegetable-based inks.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

ONeill, Patrick, 1945, author

Impossible Joyce : Finnegans wakes /Patrick ONeill.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4426-4643-8 (bound)

1. Joyce, James, 18821941. Finnegans wake. 2. Joyce, James, 18821941 Translations History and criticism. I. Title.

PR6019.O9F596 2013 823.912 C2013-903700-4

This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Canadian Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences, through the Aid to Scholarly Publications Program, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario

Arts Council.

University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund for its publishing activities.

For Trudi,

who was there

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to many, but especially to Dirce Waltrick do Amarante in Brazil; Arnd Bohm, Evelyn Cobley, Beth Coward, Michael Kenneally, Hana Stanbury, Margaret Maliszewska, and Colin Wright in Canada; Friedhelm Rathjen and Ulrich Blumenbach in Germany; Anne Fogarty in Ireland; Rosa Maria Bollettieri Bosinelli and Gerald Parks in Italy; Geert Lernout in the Netherlands; Tadeusz Szczerbowski in Poland; Marissa Aixs and Teresa Caneda Cabrera in Spain; Ruth Frehner, Fritz Senn, and Ursula Zeller in Switzerland; Robert Weninger in the United Kingdom; Tim Martin and Jolanta Wawrzycka in the United States. Thanks also to colleagues during a fellowship at the Camargo Foundation in Cassis, France, especially Rudolf Binion and Stefano Mula; to Richard Ratzlaff and two anonymous readers at the University of Toronto Press; and to Maureen Epp for her eagle-eyed copy editing.

Particular thanks are due to the National Library of Ireland in Dublin, the British Library in London, and the Zurich James Joyce Foundation, as well as to Queens University at Kingston, Canada, and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Blanket acknowledgments are of course also due to many of the standard and indispensable works of Wake scholarship: Campbell and Robinson, Tindall, Glasheen, Mink, McHugh, the numerous contributors to A Wake Newslitter, and the many contributions over the years of Fritz Senn, Joycean grandmaster. Finally, and as always, my sincere thanks are due to my wife, Trudi, for her unflagging support and tolerance over the years.

Two works appeared too late to be considered: Krzysztof Bartnickis Finneganw Tren (Krakow: Ha!Art, 2012), a complete Polish version of FW, and Congrong Dais Fennigan de Shouling Ye (Shangai: Shangai Peoples Publishing House, 2012), a Chinese version of FW I. iviii, the first of three planned volumes of a complete Chinese rendition.

IMPOSSIBLE JOYCE

Introduction

In the buginning was the woid

(FW 378.29)

Finnegans Wake is a literary machine designed to generate as many meanings as possible for as many readers as possible. Impossible Joyce: Finnegans Wakes, the present exercise in the long and widening wake of the Wake, focuses on the extended capabilities of that machine in the course of a sustained examination of transtextual effects (a concept to which we shall return) generated by comparative readings, across a range of languages, of translated excerpts from a work that has repeatedly been declared entirely untranslatable.

Fritz Senn has commented that everything Joyce wrote has to do with translation, is transferential (1984, 39). The central question with regard to a translation of Finnegans Wake, that lexicographers paradise (Magalaner and Kain 1962, 240), is whether such a possibility can be envisaged in the first place, and scholarly discussions of the issue over the past several decades have been numerous. and the alleged impossibility of the task has not deterred a number of likewise competent translators from undertaking it usually to the extent of only a page or two, admittedly, but in a small number of heroic cases (Philippe Lavergne in French, Dieter Stndel in German, Erik Bindervoet and Robbert-Jan Henkes in Dutch, Donaldo Schler in Portuguese, Chong-keon Kim in Korean, Naoki Yanase in Japanese) encompassing the entire 628-page text. Various others have published extensive though less than complete translations (Luigi Schenoni in Italian, Vctor Pozanco in Spanish, Kyko Miyata in Japanese) of the work, and yet others have translated complete individual chapters, especially the eighth chapter, a first version of which appeared in print as early as 1928 under the title Anna Livia Plurabelle.

Joyce himself, according to his biographer Richard Ellmann, had no doubts at all about the translatability of the Wake: There is nothing that cannot be translated, said Joyce (Ellmann 1982, 632). Joyce, indeed, as is well known, instigated and participated himself in both French and Italian translations from Anna Livia Plurabelle, and kept an interested eye on the progress of a German version. In so doing, he led the way in suggesting that what would become Finnegans Wake would also, all appearances to the contrary, be indeed translatable, at least in some sense of that term. Following Joyces lead, Alberte Pagn has argued that to say the Wake is untranslatable is to say that it is illegible and since an already vast body of exegesis proves that it is legible, it follows that it is also translatable (2000, 147). More provocatively, Umberto Eco has even suggested that Finnegans Wake may in fact be the easiest of all texts to translate, in that it permits a maximum of creative liberty on the part of the translator (1996, xi; translation mine). Despite Joyce, however, despite Eco, and even despite a number of highly impressive complete renderings, Finnegans Wake is still generally and by no means unreasonably regarded as an essentially untranslatable text in any normal understanding of the concept of translation.

My primary interest here, however, is not in theoretical considerations of translatability or untranslatability but rather in the comparative exploration, across languages, of textual effects generated by actual (would-be) translations. It is now a commonplace that the activity of literary translation is done considerably less than justice by an exclusive critical focus on the degree to which the results are deemed to be unwaveringly faithful to an original text. Fidelity is of course a crucial factor in the process, but so is the realization that translation itself involves a process of rewriting, of continuing the original text, a process that also presupposes both creativity and originality. A great deal has been written and no doubt still remains be written about the theory of literary translation. The specific reasons why the

Next page