Until the Industrial Revolution, humanity accepted the cyclical nature of life. Natures tides of composition and decomposition turned the small into the big and the big back into the small. Common sense held that over time all beings would find their way to dust and that dust itself formed a barrier between the visible and the invisible that could not be negotiated by the living.

JOSEPH A. AMATO

Two women are walking down the road and pass a frog sitting in the grass. Hey, says the frog.

Wow. Its a talking frog, says one of the women. She picks the frog up and holds it in her hand.

The frog says, Listen, Im not really a frog. Actually, Im a critically acclaimed writer. A spell was cast on me and I was turned into a frog. But if you kiss me Ill turn back into a critically acclaimed writer.

Well, Ill be damned, says the woman, and puts the frog in her pocket.

Her friend asks, Arent you going to kiss it?

And she answers, Hell, no. Ill make a lot more money with a talking frog.

M rs. Clark and I always took lunch together. She set a place at the breakfast bar for me right alongside her place. Two paper towels spread out to put our food on. I would pull my lunch out of my soft cooler. It was different things on different days. Sometimes an egg-salad sandwich, but usually a hodgepodge of leftovers. Mrs. Clarks lunch was almost always leftovers, too. If it was summer, she ate a raw hot pepper from her garden. And if it was autumn, she set out a tub of refrigerator pickles and let me help myself. By the time lunch was being served, The Price Is Right was on TV and Id reached the back of the house. If I had been in the house alone, I would have finished up the bathrooms before I sat down to eat. In the housecleaning trade, bathrooms and kitchens and mopping are called wet-work and I preferred to have it all behind me before lunch. It was hard to face wet-work after eating. It was not so hard to face the last bit of dusting and vacuuming and replacing the rugs.

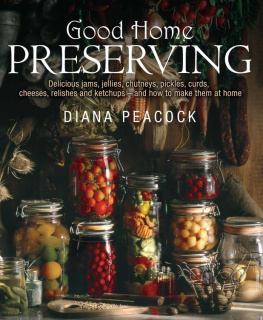

But I was never alone in Mrs. Clarks house. She didnt like for me to be there when she wasnt. I had even been asked to rearrange my schedule to accommodate a doctor or dentist appointment. She kept up a steady complaint about the price, too, telling me at every opportunity it was high enough that I should provide the garbage bags as well as the cleaners and vac bags. If I hadnt liked her so much, I would have dropped her in a minute. But I did like her. She was old and old-fashioned and I liked the way she lived. At eighty-three, she still gardened and canned and pickled and put up produce in the freezer in the garage.

I liked her house too. Everything was neat and organized and the house itself was a marvel. It was built by her late husband, and in one place, the gold-toned knotty pine paneling opened to reveal a desk with cubbyholes and shelves above it. The last papers of the late Mr. Clarks construction business were stuck to a nail hammered through a small board. It was as if they waited for him to return and get two-by-fours at the old price.

There was a picture of Mr. Clark in the living room, a black-and-white photograph of a handsome young man in a military uniform. From the same era was a picture of Mrs. Clark. She was drop-dead gorgeous, not in a glamorous, made-up kind of way but more in a healthy, capable kind of way. I bet she was a good girlfriend, and after the war, a good wife. She told me several times that when Clark (she always called him Clark) was deployed overseas, they worked out a code together. The first letter of every paragraph in his correspondence to her would spell out his location. That way she would always know where he was. And I did, shed say. The censors never caught it.

I loved to hear Mrs. Clark tell stories. Sometimes she trailed me around and talked about Clark while I dusted the living room or cleaned the kitchen. I knew a lot about Clark. I knew that whenever someone dropped by to visit, he would say, Come on in this house. And I knew he always gave bags of apples and oranges for Christmas. And I knew hed fallen off a roof once and was out of work for a month. Mrs. Clark could tell me which houses along her street her husband had built and who had built all the others.

He died at home, in the house that I cleaned. He was sick a long time and one day their daughter Patricia was in the bedroom with him and he passed away with Mrs. Clark just on the other side of the wall hed built. Mrs. Clark told me about Patricia coming into the living room and saying, Hes gone, Mama, and Mrs. Clark saying, And you didnt come get me. I could tell that it still upset her.

He might not have been able to go with you in the room, I told her. Im sure it was hard to leave you here.

Mrs. Clark looked away. Well, there wont ever be another like him, she said.

She had a guitar in her closet and one day I asked her about it. Did Clark play?

Its mine, she said.

She brought it out, slung the strap over her shoulder, tuned it, and picked a fast song. Then the guitar went back into the case and the case went back into the closet.

All the closets were lined with cedar and in the fall there would be box tops spread with newspaper and filled with green tomatoes picked just before first frost. I loved the seasons in Mrs. Clarks house. They had as much to do with the garden as they did with holidays, but holidays were clearly important. There were pictures to prove it. Her family took pictures of everything. Besides fifty years worth of Christmas trees and Thanksgiving dinners, there were pictures of mundane things, like Patricia and the tenant from the garage apartment shoveling snow off the driveway, and even one of the big hole in the backyard, where the water department dug up an old gas tank.

Mrs. Clark kept the pictures arranged in albums. They marched in a neat chronological parade along one of the built-in shelves in the living room.

At Christmas she got cards from everyone who had ever rented the apartment above the garage or the attic bedrooms that were now closed off. She taped the cards to the doorframe between the kitchen and the living room. This was when Mrs. Clark was most likely to take her picture albums out and point to a card and then the picture of the person who had sent the card.

That she had pictures of every tenant theyd ever had amazed me. It amazed me even more that Mrs. Clark knew their names, and still got cards from them. Sometimes she pointed to photos of the kids, or the couple she and Clark went out with every Friday night. Once she pointed to a picture of their maid, a smiling black woman named Real.

I asked Mrs. Clark about it several times when she first showed me Reals picture. Real? Her name was Real?

Yep. Real.

Thats a great name, I said, cataloguing it in my mind for a future character.

She was a great woman, Mrs. Clark said. She was with us seventeen years. Came in every day. Got sick and had to quit and we miss her.

I tried to imagine Real. She probably dusted many of the same things I was dusting and she probably got along with the Clark family pretty well. They were a happy bunch. They werent mean and they worked hard and they didnt expect miracles and there were certainly worse white people to work for. But I bet it was hard on her too. Real must have had her own children to tend to. Im sure there were meals to fix at home, floors that needed sweeping and mopping, dishes that needed washing, and sheets that needed changing. I could sympathize with Real regarding that, because for me this has always been one of the toughest things about working as a housecleaner. I scrubbed and dusted and mopped all day long and then came home to a dirty house. I imagine this irony was not lost on Real.