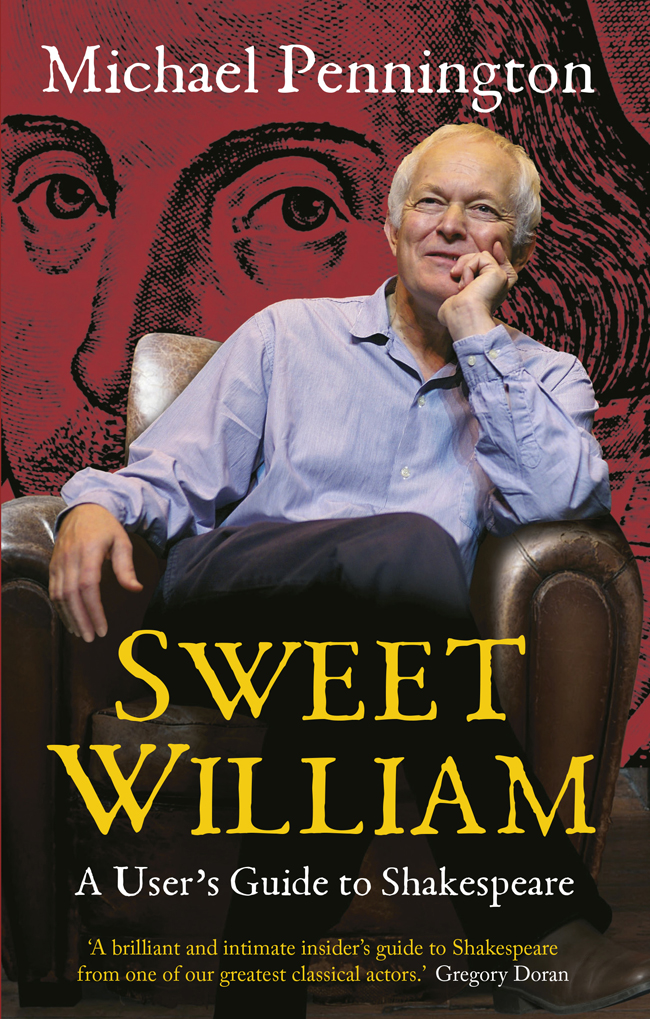

Michael Pennington

Sweet William

A Users Guide to Shakespeare

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Contents

For my parents

Preface

Whatever their angle of approach, Shakespeare books could hardly be unaware of each other. So I have learned from and had suspicions confirmed by Peter Ackroyd, Andrew Dickson and Charles Nicholl, and by Professors Jonathan Bate, Stephen Greenblatt, James Shapiro and Stanley Wells. My thanks as always to Nick Hern, editor par excellence, and to Nick de Somogyi, a fine and genial Shakespearian sleuth who can spot a textual inaccuracy at twenty paces. It is hard to imagine this book getting to this point without Prue Skene; Mark, Louis and Eve Pennington have refreshed views of mine on the plays that I thought forever entrenched, despite or because of being, in two cases, fifty years younger than I am. There are many others who have encouraged me, at work and play and over a great space of time; they are too numerous to mention without offence to the unmentioned. I was about to say that they know who they are, but in many cases they dont; actors and writers are heartened by all sorts of people they never even meet.

As for the chronology and dating of the plays, Ive always thought it was, beyond a certain point, something of a mugs game. So I havent supplied a conventional list of speculative dates. Given the circumstances of Shakespeares working life, the moment of a plays composition is likely to be immediately before its premiere; but the date of publication can be a very different and quite vexing matter. So while the birth of a handful can be happily identified by the date of their first recorded performances, that of others can only be established as being some time before a known event, such as publication, or after another, such as some topical reference in the play. In the face of only the vaguest consensus, I tend to fall back with a shrug: after all, unlike the scholars, I feel no special burden of proof here.

The search is in any case less interesting than you might think or than it would be with another author. Outside of his Sonnets, Shakespeares lived life seems to have left very little mark on his work; and as a writer he seems to have arrived fully formed, both inspired and fallible. Throughout his career the supreme and the rough and ready sit side by side: in among apprentice works like Henry VI and King John lie masterpieces such as A Midsummer Nights Dream and Romeo and Juliet. Tone of voice is no more reliable: the great tragedy of Hamlet is immediately followed by the comic glories of Twelfth Night. Nor is theme: the treatment of marital jealousy in The Comedy of Errors (1594) has something in common with The Winters Tale (1611). Throughout, Shakespeare maintains a resolutely private stance what Chekhov later identified as autobiographobia. He wrote a series of comedies directly after his sons death; on establishing himself in London he bought a house in Stratford, and on the point of returning to Stratford he bought one in London.

Still, the rough sequence of events seems to have been this. Shakespeare arrived in London in 1592 and wrote plays for just over twenty years: occasionally, at the beginning and end, with a little collaboration. His debut may have been with The Two Gentlemen of Verona or it could have been Titus Andronicus, or The Taming of the Shrew, or one of the Henry VI plays. Of the twenty-five or so he wrote in the first half of his career, roughly up until the death of Queen Elizabeth in 1603, a large proportion are history plays indeed with the exception of Henry VIII, all his ten Histories lie in this decade. This period also features some boxoffice favourites The Merchant of Venice, Much Ado About Nothing, As You Like It, Julius Caesar. In the second phase the pace slows down from approximately two to a little more than one a year if you can call Othello, King Lear, Macbeth and The Tempest any kind of slowing down. When plague struck, as it regularly did and closed the theatres, Shakespeare wrote poetry primarily The Rape of Lucrece, Venus and Adonis and the Sonnets which he finally collected together for publication in 1609.

In 1599 the Globe Theatre opened. In 1603 Elizabeth I died and James I succeeded a most significant date to keep in mind, in my view. In 1609 Shakespeares company began to use the indoor Blackfriars Theatre, though they continued to play at the Globe in the summer. The Globe burned down in 1613, and was rebuilt the following year. Shakespeare died in 1616. The first complete edition of his works was published in 1623. The new Globe was closed, as was the Blackfriars and all other London theatres, by the Puritans in 1642, and was probably destroyed in 1644. The Blackfriars was demolished in 1655.

The quotations in my text are not consistently taken from any particular Folio or Quarto, but are the versions I have myself become used to: editorial comparisons and textual variants are available elsewhere. The section at the end about phrases Shakespeare invented owes something, though not all that much, to Bernard Levin. I have T.S. Eliot to thank for the insight into Charmians dying line in Antony and Cleopatra, and Philip Franks for his recollection of Donald Sindens Benedick All mistakes and eccentricities are, of course, my own.

Michael Pennington

Introduction

I n 1827 the composer Hector Berlioz went to see an English company perform Hamlet in Paris. Hed never seen a Shakespeare play before in fact he spoke no English but that evening he fell in love with the play, with the author, and with Harriet Smithson, the actress playing Ophelia:

Shakespeare coming upon me unawares, struck me like a thunderbolt I saw, I understood, I felt that I was alive and that I must arise and walk.

I have little in common with Berlioz, but Shakespeare hit me like a hammer when I was eleven. I had the advantage of speaking English, but no more natural affinity with Shakespeares world than might any other Tottenham Hotspur supporter of that age. The play was Macbeth, at the Old Vic Theatre in London, and it certainly wasnt my idea to go; and my parents, who took me, were only supposing in the vaguest terms that it would be Good For the Boy to see a Shakespeare play at some point before adolescence carried him off into the unknown.

Little did they guess. The show started with a bloodcurdling scream that came slicing out of a darkness which then lifted to reveal a bloodsoaked soldier staggering towards us and collapsing; and a moment after that, from a tangle of dead trees and twisted branches behind him, the figures of the three weird sisters arose to ask when they would meet again in thunder, lightning or in rain. Two lines in, I was on the edge of my seat; and, the play being what it is, I stayed there all night. Macbeth was played by the fine Paul Rogers; as he contemplated the murder of King Duncan, he also saw what he was about to do to himself:

Besides, this Duncan

Hath borne his faculties so meek, hath been

So clear in his great office, that his virtues

Will plead like angels, trumpet-tongued, against

The deep damnation of his taking off;

And pity, like a naked new-born babe,

Striding the blast, or heavens cherubim, horsd

Upon the sightless couriers of the air,

Shall blow the horrid deed in every eye,

That tears shall drown the wind.

I couldnt quite work out this wonderful picture, but its power and fluency sounded like a great rumbling organ with all its stops open. A few minutes later Macbeth saw his imaginary airborne dagger and followed it slowly, slowly, slowly towards Duncans bedroom to do the deed: