All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Scribner Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

SCRIBNER and design are registered trademarks of The Gale Group, Inc., used under license by Simon & Schuster, Inc., the publisher of this work.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

To the memory of Paul Cowan (19401988) and J. Anthony Lukas

(19331997), two heroes I never got a chance to meet.

PREFACE

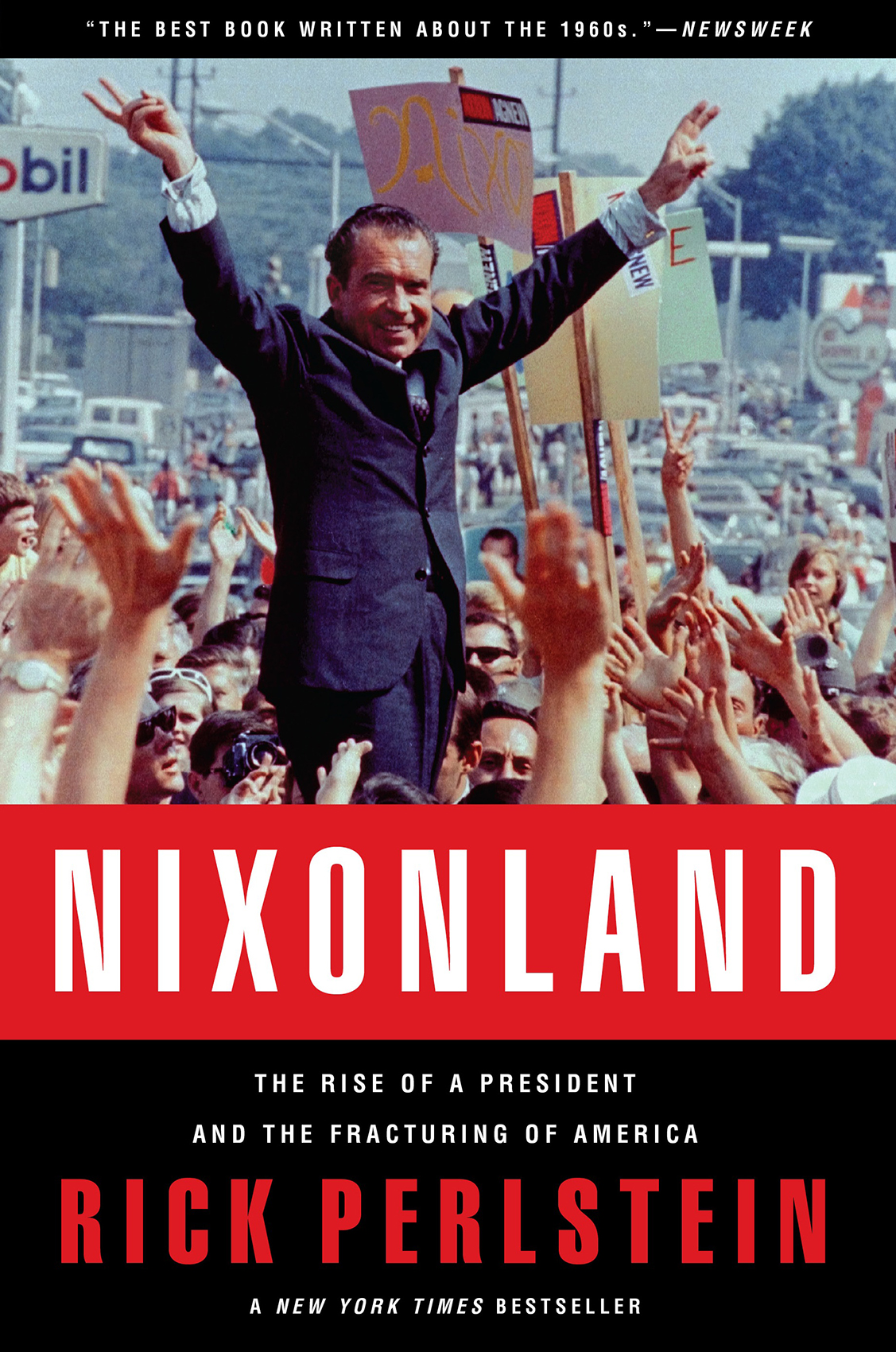

I N 1964, THE D EMOCRATIC PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATE L YNDON B. J OHNSON won practically the biggest landslide in American history, with 61.05 percent of the popular vote and 486 of 538 electoral college votes. In 1972, the Republican presidential candidate Richard M. Nixon won a strikingly similar landslide60.67 percent and 520 electoral college votes. In the eight years in between, the battle lines that define our culture and politics were forged in blood and fire. This is a book about how that happened, and why.

At the start of 1965, when those eight years began, blood and fire werent supposed to be a part of American culture and politics. According to the pundits, America was more united and at peace with itself than ever. Five years later, a pretty young Quaker girl from Philadelphia, a winner of a Decency Award from the Kiwanis Club, was cross-examined in the trial of seven Americans charged with conspiring to start a riot at the 1968 Democratic National Convention.

You practice shooting an M1 yourself, dont you? the prosecutor asked her.

Yes, I do, she responded.

You also practice karate, dont you?

Yes, I do.

That is for the revolution, isnt it?

After Chicago I changed from being a pacifist to the realization that we had to defend ourselves. A nonviolent revolution was impossible. I desperately wish it was possible.

And, several months after that, an ordinary Chicago ad salesman would be telling Time magazine, Im getting to feel like Id actually enjoy going out and shooting some of these people. Im just so goddamned mad. Theyre trying to destroy everything Ive worked forfor myself, my wife, and my children.

This American story is told in four sections, corresponding to four elections: in 1966, 1968, 1970, and 1972. Politicians, always reading the cultural winds, make their lifes work convincing 50 percent plus one of their constituency that they understand their fears and hopes, can honor and redeem them, can make them safe and lead them toward their dreams. Studying the process by which a notably successful politician achieves that task, again and again, across changing cultural conditions, is a deep way into an understanding of those fears and dreamsand especially, how those fears and dreams change.

The crucial figure in common to all these elections was Richard Nixonthe brilliant and tormented man struggling to forge a public language that promised mastery of the strange new angers, anxieties, and resentments wracking the nation in the 1960s. His story is the engine of this narrative. Nixons characterhis own overwhelming angers, anxieties, and resentments in the face of the 1960s chaossparks the combustion. But there was nothing natural or inevitable about how he did itnothing inevitable in the idea that a president could come to power by using the angers, anxieties, and resentments produced by the cultural chaos of the 1960s. Indeed, he was slow to the realization. He reached it, through the 1966 election, studying others: notably, Ronald Reagan, who won the governorship of California by providing a political outlet for the outrages that, until he came along to articulate them, hadnt seemed like voting issues at all. If it hadnt been for the shocking defeats of a passel of LBJ liberals blindsided in 1966 by a conservative politics of law and order, things might have turned out differently: Nixon might have run on a platform not too different from that of the LBJ liberals instead of one that cast them as American villains.

Nixons win in 1968 was agonizingly close: he began his first term as a minority president. But the way he achieved that narrow victory seemed to point the way toward an entire new political alignment from the one that had been stable since FDR and the Depression. Next, Nixon bet his presidency, in the 1970 congressional elections, on the idea that an emerging Republican majorityrooted in the conservative South and Southwest, seething with rage over the destabilizing movements challenging the Vietnam War, white political power, and virtually every traditional cultural normcould give him a governing majority in Congress. But when Republican candidates suffered humiliating defeats in 1970, Nixon blamed the chicanery of his enemies: America s enemies, he had learned to think of them. He grew yet more determined to destroy them, because of what he was convinced was their determination to destroy him.

Millions of Americans recognized the balance of forces in the exact same waythat America was engulfed in a pitched battle between the forces of darkness and the forces of light. The only thing was: Americans disagreed radically over which side was which. By 1972, defining that order of battle as one between people who identified with what Richard Nixon stood for and people who despised what Richard Nixon stood for was as good a description as any other.

Richard Nixon, now, is long dead. But these sides have hardly changed. We now call them red or blue America, and whether one or the other wins the temporary allegiances of 50 percent plus one of the electorateor 40 percent of the electorate, or 60 percent of the electoratehas been the narrative of every election since. It promises to be thus for another generation. But the size of the constituencies that sort into one or the other of the coalitions will always be temporary.

The main character in Nixonland is not Richard Nixon. Its protagonist, in fact, has no namebut lives on every page. It is the voter who, in 1964, pulled the lever for the Democrat for president because to do anything else, at least that particular Tuesday in November, seemed to court civilizational chaos, and who, eight years later, pulled the lever for the Republican for exactly the same reason.