ALSO BY MELISSA HOLBROOK PIERSON

The Perfect Vehicle:

What It Is About Motorcycles

Dark Horses and Black Beauties:

Animals, Women, a Passion

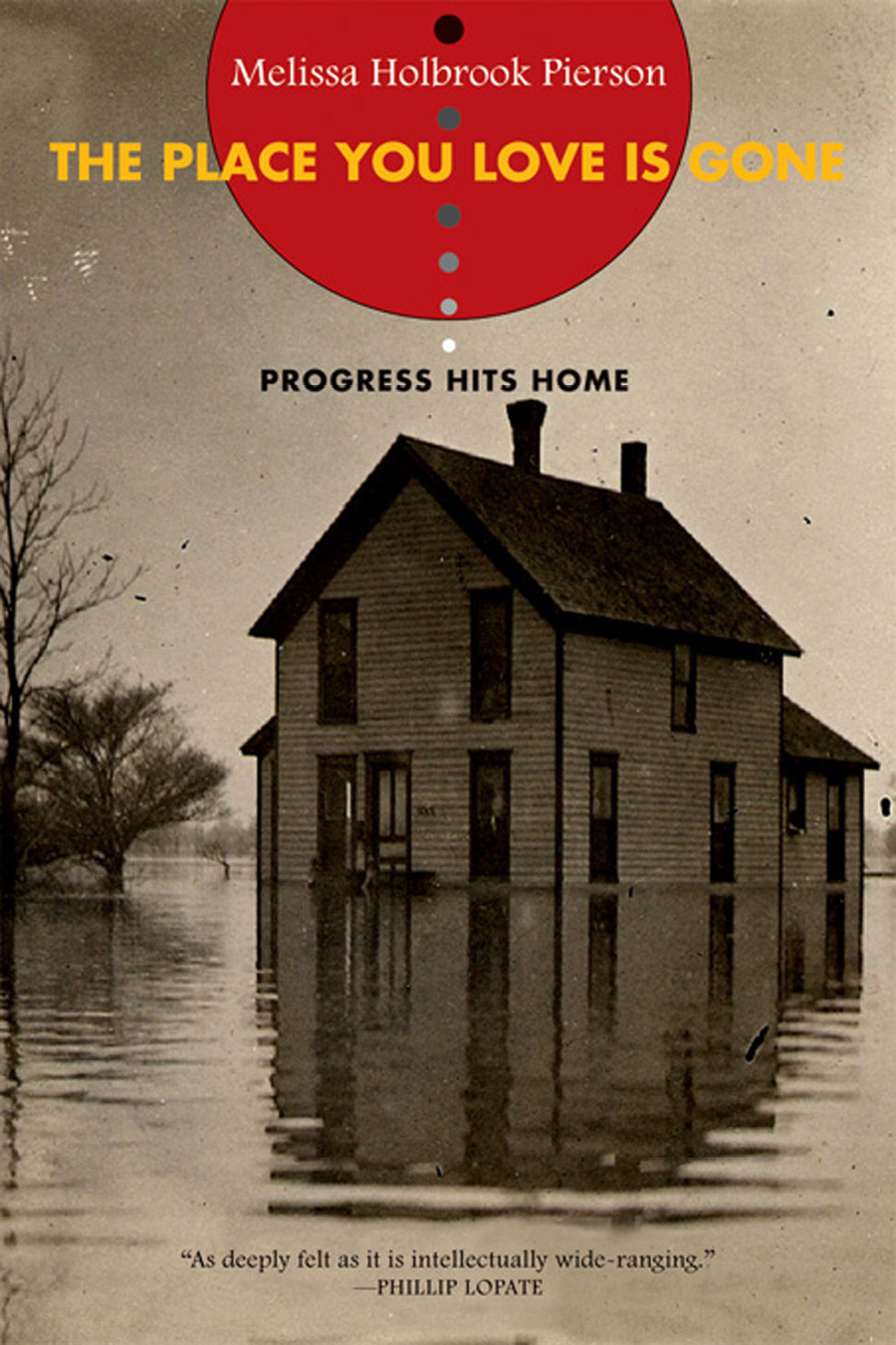

MELISSA HOLBROOK PIERSON

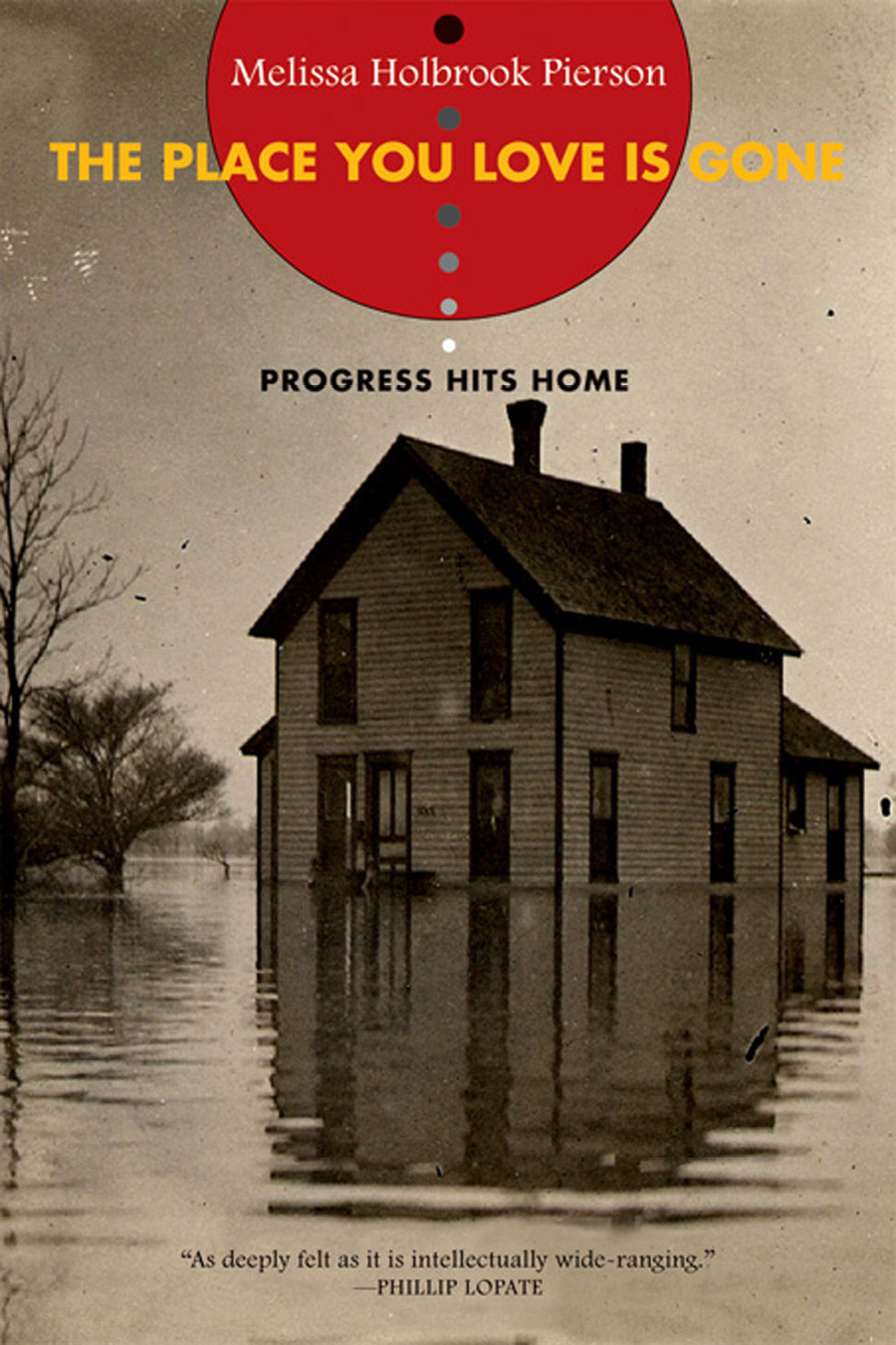

THE PLACE YOU LOVE IS

GONE

| PROGRESS HITS HOME |

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY  NEW YORK LONDON

NEW YORK LONDON

CONTENTS

To my father,

Charles Pierson,

19222003,

and the places he loved

HOME TOWN

I am a fragment, and this is a fragment of me.

E MERSON , Experience

Y OU ARE A GIGANTIC , unknowable, towering, tragicomic construction. You can also be traced back to a cell. But this cell needed to meet with bizarre chance so that it was this amoeba (and not that other amoeba) that washed up onshore and started changing shape. Had the weather been slightly different that day, or the sand a tad more wet, the trajectory of the pinball would have been altered by a fraction of a degree. Then it would have banked off the side at a different angle, hit the bumper below the other one, vibrated between bumpers fourteen times instead of twelve with the attendant bells and racking up of points, and finally flushed after one and not two successful applications of the flipper.

For me, that fraction of a degree, hard as it is to grasp, is what was ultimately responsible for the existence of Garners, a hamburger drive-in on West Market Street. And Garners is where, in 1954, after some onion rings served in a plastic boat, a certain pleasantly anxious question (Will you...) was posed and breathless answer received. Since that conversation took place between two people who are responsible for making me, as far as I am concerned Garners is where the world began.

Others think some things obvious, but I have long been prone to marveling. Odd fluke and inexplicable accident are all thats between you and the hard specificity (the deep red brick of these houses... the drive to Skyway in Fairlawn on a spring evening with the windows down) of all that you love. This is the only reason that Akron, Ohio, is the punch line of a joke to everyone else but to me nothing less than the contents of a secret vault stored deep in the moist center of my soul. Go ahead, then, and laugh, but only if you have never gone down to the Cuyahoga Valley all red-gold in fall, or visited your daddys office downtown on Main Street in order to feel like the most privileged eight-year-old on earth. Anyone is excused who has not spent moments that turned into weeks that turned into years metabolizing every particle of this hilly green place until it became part of the structure of your skin, bones, teeth. Because no one but the native born can know what it is like to have West Market Street mapped as a straight line through the heart. And it does not matter that West Market Street and its merchants, its old houses and new businesses, stoplights and street signs, are as unremarkable as those on the traversing artery of any medium-sized city in the country, or many other countries. Then again, that both does not matter and it matters a great deal. This is in fact the crux of it all. It has been scientifically corroborated, too. Heres a way-finding study published in 1932, Spatial Integrations in a Human Maze. Some subjects developed affection for landmarksincluding a rough boardsimply because they were familiar. I think for a moment about an unforgettable piece of wood. Aha! This must explain my fondness for Akron.

Somewhere the great theorists of child psychology have isolated the developmental mechanisms that lead to this passing strange love. They have outlined the innate human inclination toward geography, for here the baby traces the map of mothers face with his fingers, over rills and crevasses and seismic disturbances. He feels them with an intensity that does not even recognize their separateness from his own regional being. Somewhere they have written of the grave importance of babys crib, the bars of which are transformed into a wooden womb beyond the womb. A little later, the circus mobile comes into view and it, too, along with the shadows on the wall and the Little Boy Blue nightlight, are subsumed within the known limits of the world.

How many hours there are to study their mysteries! Colors, beads, light. You have no idea what they really are. Maybe that is why they become impaled on the memory as something incredible. They will be recalled years later with a sharp intake of breath when the little child who has been somehow left to rattle around intact inside the adult suddenly spies some of these inscrutable objects on a return trip home.

One of these eminent men gave it a name: the microsphere. In other words, the repository of things. One morning you woke to find that a large rabbit had left something on the dresser in your room. You cautiously approached. At first you could do nothing but stare at this totality of wonders; indeed, staring at it was more delicious than anything else you could possibly conceive of doing with it. A papier-mch egg gave up its glossy surface to bipedal hares with wheelbarrows and garden tools. Another eggO bliss untold!appeared to be frosted like a cake, but it contained a window on a miniature scene inside. The longer you looked, the more you took in of the quality of air and light surrounding the small sugar place you now inhabited, too.

The things you saw became your home. And they became your teachers. They made you an unwitting wizard, an accomplished if pint-sized engineer. Just by looking at them, you caused things to shift shape. After hours of staring at that oxidized-green copper ornament on the roofline of your grandparents Tudor-style house (your back slightly damp from lying in the shady grass), it revealed itself in certainty: it was a frozen-custard cone. Why would there be ice cream on the roof of a house? Well, to make you look at it in longing, of course.

All the evidence is buried too near the surface, hastily, just a few inches of dirt scratched over the top of the cache. A song is heard distantly on the wind. Little lunchbox, little lunchbox, little lunchbox o mine. Here, the tin barn with thermos silo. There, the pink ballerina. Another, simple and familiar, loved therefore: red plaid. They contain the memory of lunches pasta peculiar smell, of sandwiches curing during the hours between breakfast and noon; long-ago spilled soup and applesauce; the je ne sais quoi imparted by wax paper to the whole perfume. How you longed for the Wonder Bread of your mates; how you decried the Pepperidge Farm White of your box. Crusts, begone! Yet, yet... sometimes there were Fritos. Years later, the big Time-Life Picture Cook Book and its Kodachrome photos of dinner parties circa 1956, barbecues and picnics and Cooking for Children (you memorized every chocolate chip and candy apple, the braids on the blue-jeaned girl with her hands full of wet taffy), cause successive frissons to run down your spine with every turn of the page. You must have studied this book with an intensity never rivaled in college art history. You gazed so long into its ravishing pages that you popped out the other side, crouching in the corner of the prairie-style living room in which a dazzling cocktail party was being held, at the exact moment a little boy in sport coat and diminutive bow tie forever reached for a party frank speared through by a toothpick. Or is it simply that the quality of your sight then was that of a different species?

Next page

NEW YORK LONDON

NEW YORK LONDON