Table of Contents

Books by James Salter

The Hunters (1957)

The Arm of Flesh (1961)

A Sport and a Pastime (1967)

Light Years (1975)

Solo Faces (1979)

Dusk and Other Stories (1988)

Burning the Days (1997)

Cassada (2000) (rewritten version of The Arm of Flesh)

Gods of Tin (2004)

Last Night (2005)

There & Then (2005)

Life is Meals (2006)

Books by Robert Phelps

Heroes and Orators (1958)

Letters of James Agee to Father Flye (1962)

Twentieth-Century Culture: The Breaking Up (1965)

Earthly Paradise (1966)

The Literary Life (1968)

Professional Secrets (1970)

Belles Saisons: A Colette Scrapbook (1978)

Letters from Colette (1980)

The Collected Stories of Colette (1983)

Colette: Flowers and Fruit (1986)

Continual Lessons (1990)

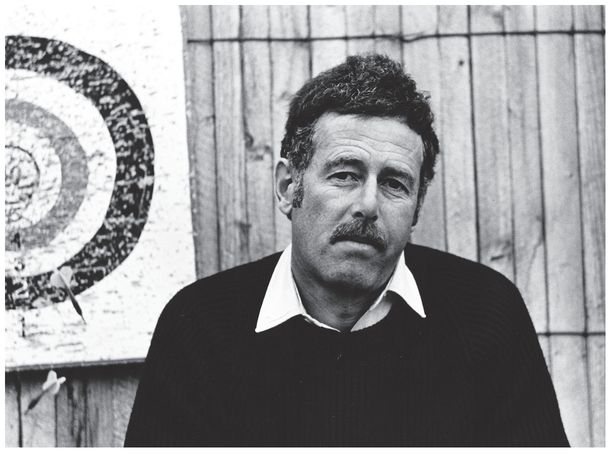

JAMES SALTER

ROBERT PHELPS

Foreword

By Michael Dirda

As one reads through the correspondence between Robert Phelps and James Salter, it gradually becomes clear that these are love letters. The talk is of the literary life, of magazine pieces, plays and movies, of revered makers like Colette and Stravinsky, of long walks in Greenwich Village and loneliness in Aspen, Colorado. But quite plainly the two writersboth married, both moving in glamorous circlescannot get enough of each other. Six months after they first meet, Salter writes from Colorado: Why dont you work here? I miss you and theres nobody to speak avec.

Nearly anyone who ever spent an afternoon or evening with Robert Phelps will attest to his wondrous charm. Composer Ned Rorem, writers Dan Wakefield and Stephen Koch, poet Richard Howardall these have memorialized Roberts perennial youthfulness, his generosity of heart and spirit, his genius for friendship. At a recent panel on New York in the 1950s, sponsored by the Associated Writing Programs, Phelps was named the very embodiment of that eras literary life.

He and I first met in May of 1968, when I was nineteen years old. I was on my way to a summer in France and en route stopped in New York, my very first visit to the city. Somehow I managed to figure out the subways and eventually emerged at Union Square, then strolled, wide-eyed, through bright sunshine to 6 East 12th Street. After Id rung the buzzer on the mailbox, Robert came bounding down the stairwell, two steps at a time. He was the father of my college roommate but might have been his brother: black tousled hair, white T-shirt, corduroy jeans, Clark Wallabees on his feet and a boyish grin on his face. We trudged up the steps to his book-lined eyrie on the fourth floor, and by the end of that afternoonof literary gossip, accompanied by two robust Tanqueray martinisI was drunk. I also knew that I wanted more than anything in life to be him.

We came from similar backgrounds. I grew up in Lorain, Ohio, eight miles from his hometown of Elyria; I was attending Oberlin College, where hed spent a year or so. Most of all, though, I too had long dreamed about being a writer in New York, of living by my pen and wits in an apartment full of booksreal, hardcover books. On that first day, Robert showed me a set of uncorrected page proofs of Randall Jarrells The Third Book of Criticism, which hed been assigned to review. Id never seen page proofs before. Little did I know that I was looking at my own future.

At that time Robert and his wife, the painter Rosemarie Beck, shared a large two-room apartment with kitchen and bathroom. But Robert actually worked in a little cubby off the brownstones stairwell on the second floor, a kind of janitors closet fitted out with a desk and a chair and a few shelves. Its window looked out on 12th Street, and sometimes passersby could glimpse the writer or his shadow typing away. Only later were Robert and Becki able to rent another floor in their building so that he was finally able to furnish a room of his own.

Naturally, Robert transformed this new space into what Auden once called a cave of making. The wooden floors were stained black, the walls completely lined with bookshelves. Curtains, usually kept drawn, blocked out both day and night. A pole lamp stood next to a rather high-tech chrome and leather easy chair, and extension lights were clamped to the corners of bookcases. On a coffee table in the middle of the room there always lay page proofs, literary magazines, publishers catalogues. Instead of a sofa, a daybed butted up against the back of a freestanding bookcase and was covered with pillows embroidered with scenes from classical mythology (Beckis handiwork). They were like small Poussins in needlepoint. Near the music cornerlots of Stravinsky, Poulenc, and Ravel LPsstood a long, low set of white shelves, on top of which rested more books, some heavy tumblers, and a big bottle of Tanqueray gin.

The books in Roberts library were read again and again, underlined and marked up, made very much his own. Since he preferred the muted tonal-ities of book cloth, few had kept their bright and garish dust jackets. But before discarding the djs, Robert would sometimes cut out the author photos and glue them into an oblong album labeled The Poets Face. Amplified with chronologies, lists and anecdotes, this eventually became his lovers homage to writers and writing, The Literary Life: A Scrapbook Almanac of the Anglo-American Literary Scene from 1900 to 1950 (coauthored with his friend Peter Deane).

So it was that in this comfortable living room-bedroom-study, Robert padded about, surrounded by his favorite authors, most of whose works he owned, in toto: W. H. Auden, Colette, Cyril Connolly, Glenway Wescott, Louise Bogan, Jean Cocteau, Marcel Jouhandeau, James Agee, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Rayner Heppenstall, Paul Lautaud, Brigid Brophy. Pick out one of their well-worn books from the shelves, and you might find inside an old postcard from the author; or a quotation copied onto the endpapers (Art is concerned with production Aristotle, appropriately in a bibliography of Henry James); or a review clipped from a newspaper; or even, in the case of T. S. Eliot, a commemorative postage stamp. In his copy of Robert Lowells Lord Wearys Castle, Phelps noted that in 1946 he had stolen the book from a department store in Cleveland. A first edition, too. When Robert Phelps loved a book, it became his book, as much as the authors.

Roberts work desk was simplicity itself: a sheet of painted plywood across two low metal filing cabinets. Near at hand, reference works: a Larousse French dictionary, the Concise Oxford English Dictionary, the little Annals of English Literature 1475-1950 (the principal publications of each year together with an alphabetical index of authors with their works). Robert craved facts, dates, and odd particularities and once expounded a theory about Shakespeares love life, based on a careful study of the birthdays and stage productions listed in Charles Williamss concise version of E. K. Chamberss biography. He speculated, with a Jesuitical logic that Stephen Dedalus would have envied, that the bards brother must have cuckolded him. As I recall, on that same afternoon, he mock-solemnly intoned that a critic really only needed to know three things about writers: their sexual tastes, the state of their health, and where or how they got their money.

![James Salter - A sport and a pastime : [a novel]](/uploads/posts/book/43559/thumbs/james-salter-a-sport-and-a-pastime-a-novel.jpg)