REIVER

By David Pilling

Now Liddesdale has ridden a raid,

But I wot they had better stayed at hame.

For Peter Winfield he is dead,

And Jock o'the Side is prisoner taken.

Jock o the Side

GLOSSARY

Bairn Border slang for child

Bastle fortified barn for cattle

Burgonet a kind of visored helmet

Caliver a type of light musket

Corbies ravens

Dag type of wheellock pistol

Handbaw a ball game played on the Border

Hobbler breed of Border pony

Laird lord/chieftain

Nolte/Kyne Border slang for cattle

Morion helmet with a ridged crest

Reiver Border slang for raider/robber

Slew-hound breed of Border hunting dog

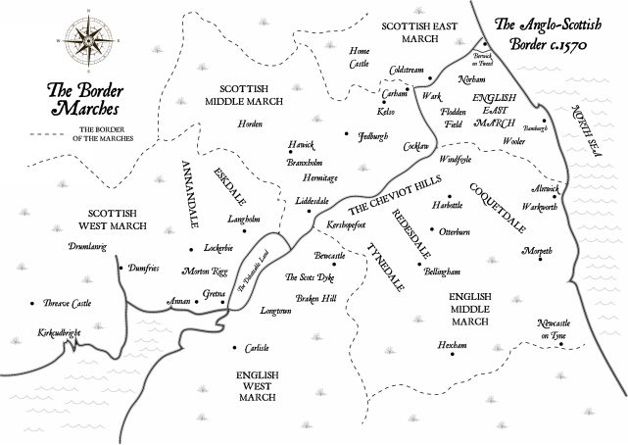

Hoof beats drummed over the tops. Twelve strong thieves of Liddesdale, mounted on good ponies and armed for war, left their dark valley at dead of night.

Across the broad waste they rode, in mist and rain, over the border into Redesdale. Two hours after midnight, their way lit by a swollen moon, they arrived within sight of their target.

The place was called Crowhame. A village of sorts, six timber cabins clustered at the head of rain-drenched hills. There was a farmhouse also, a strong place of stone, larger than the cabins. Beside the farmhouse loomed the silhouette of a fortified bastle. Its rugged shape clung to the slopes like a slumbering beast. The inbye fields, surrounded by ditches and watered by a burn, were a little way down on flatter ground.

From there could be heard the grunts and snuffles of kyne, nosing about for tufts of grass. A hay barn and a stable lay at the edge of the fields. Firelight glowed under a shelter between the timber buildings.

The riders slowly picked their way down into the fields. Wrapped up in their cloaks, the Liddesdale men were expert at moving in speed and silence.

Inside one of the cabins Richie Reade stirred in his sleep. His dreams were disturbed of late, full of dread premonitions: muddied fields strewn with dead soldiers; a burning Bible cut loose from its altar, hallowed pages scattered across the flagstones; a red bull, steam rising from its nostrils, bounding over a red river.

Ruth, his mate, turned over and draped a slender arm over his chest. She was fourteen, he two years older. They had been handfasted the previous autumn, before the blasts of winter came. If they sorted well together, the marriage would take place in the spring. If not, Ruth was free to break with him and look for a more suitable mate.

Richie's eyes snapped open. His dreams evaporated. Despite the cold of the night, his skin prickled with sweat. A fire burned low on the flat stone hearth the fire was always kept burning, night and day but it gave off little heat. Beside the hearth a black iron pot bubbled with lukewarm pottage.

He gently lifted Ruth's arm and sat upright. Dead silence reigned inside and out. His instincts screamed at him to listen beyond the silence, to heed his worst fears and act on them.

Richie slowly hooked a leg out of bed and reached for his jerkin and breeches, dumped in a pile on the earthen floor. Careful not to wake Ruth, he reached for his short cutting sword, propped against the wall, and belted it on.

The shaft of a longbow and a sheaf of grey-feathered arrows rested beside the door. Richie snatched up the bow, quickly strung it, snatched a fistful of arrows. He lifted the bar on the door and crept outside, barefoot, into freezing darkness.

He trod over wet grass. A cold wind sighed across the hills and knifed through the wool of his jerkin. Richie ignored the chill and damp and peered down at the white fields.

The Reades were no fools. A fire was kept burning all night beside the byres, with two men and a dog on watch. In recent weeks cross-border raids had become ever more frequent, though as yet their village had been spared.

Our turn will come. The bastards won't find us unprepared. We are no man's prey.

These words, spoken by Richie's uncle Archie, echoed in his mind. He grimaced when he remembered who was on watch: Patie's Adam and Walter Reade. Neither man could stand the other, and Patie's Adam was a hopeless drunk. Uncle Archie, headman of the village, could scarce have chosen a worse pair to sit through the long hours of winter darkness together. Unless Adam had drunk himself into a stupor, both men could be at each other's throats by now.

Richie crept a few paces down the hill. Inwardly he cursed himself. Jumping at shadows in the night? How his kinsmen would laugh. A Reade was supposed to be made of harder stuff. Yet it paid to be alert.

He froze. Below him, near the fire, the dog had started to bark. At least one of the sentries was on their guard. Then he heard Walter's rough voice raised in anger.

Quit your noise, you dull beast! Here here, what's that? Riders! Adam, wake up, man!

Then the clop of hoofs, the jingle of harness. A shot rang out. Walter shrieked in pain. The dog's barks rose to a frenzy. A yell, followed by muffled curses. Another shot, and the dog fell silent.

Slay that loon! Anton, run me a lance through his liver!

A stranger's voice, gruff and full of menace. Richie picked out an arrow and twisted his head.

Awake! he bawled at the top of his voice. Liddesdale is upon us! Arm yourselves! A rescue, a rescue!

The hoof beats drummed ever louder. A figure hove into view, scrambling on all fours up the slope. Adam's pale face, distorted with terror, glinted in the moonlight.

Richie! he cried. Help me, in Gods name!

A reiver on a black hobbler loomed behind him, breastplate gleaming, face invisible under a steel cap. The reiver hurled his lance. Adam flung his head back in a noiseless scream, mouth wide open, hands clawing at the lance-head burst through his chest.

Richie planted his arrows in the turf, chose one and notched it to the string. He was most at home with a bow in his hand. For the past three years running he had won the prize at the butts at Carlisle fair, where he was known as Richie Othe Bow.

He took aim at the reivers hulking shadow, drew the string back to his ear and loosed.

Even in near-pitch darkness, Richie was a good shot. The arrow hit the reiver square in the face and bowled him out of the saddle. He dropped without a sound and hit the grass. His hobbler, suddenly deprived of her mount, tossed her shaggy head and plunged away into the night.

Richies blood ran cold. It had nothing to do with the night chill. He knew these reivers were most likely Liddesdale men, riding surnames; Armstrongs and Elliots and Crosiers and their ilk. If any man killed one of them, by fair means or foul, he was made the subject of deadly feud. His victims kin would not rest until he lay dead at their feet.

There was no time to think of that now. More reivers came galloping through the murk, lit up in devilish silhouette by the fire. They cried out at the sight of their dead comrade and veered aside to avoid trampling his body.

Richie turned and scrambled back up the hill, hoof beats thudding in his ears. Above him lights flared in the doorway and upper windows of the farmhouse. The villagers had heard his warning. They spilled from their dwellings, men and women and bairns, all bristling with weapons: swords and lances and bows, one or two Jedburgh axes. A man cursed as he rammed the wadding down the long barrel of his caliver. The clumsy, new-fangled weapon was still unpopular along the Border, where men preferred to cling to the longbow.

Richie spotted his uncle among them. Long white hair streaming in the wind, Archie wore only his patched breeches and brandished a dag in his right hand. To the old mans left stood Ruth, barefoot in her white shift, clutching a spear.

Next page