Pagebreaks of the print version

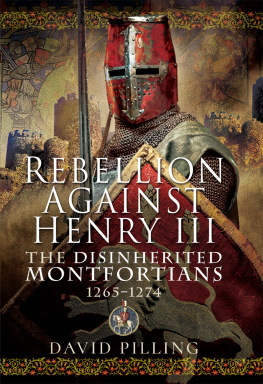

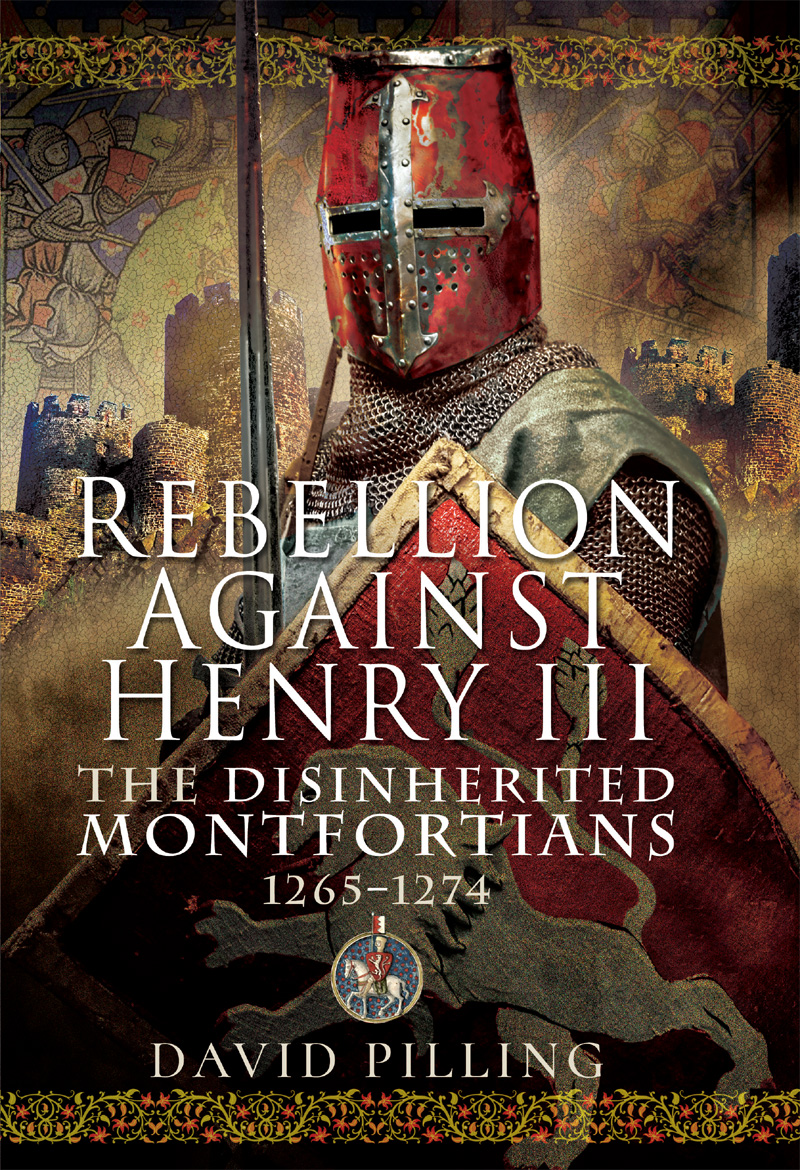

REBELLION AGAINST HENRY III

REBELLION AGAINST HENRY III

The Disinherited Montfortians, 12651274

DAVID PILLING

First published in Great Britain in 2020 by

PEN AND SWORD HISTORY

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire Philadelphia

Copyright David Pilling, 2020

ISBN 978 1 52676 320 4

ePUB ISBN 978 1 52676 321 1

Mobi ISBN 978 152676 322 8

The right of David Pilling to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

Introduction

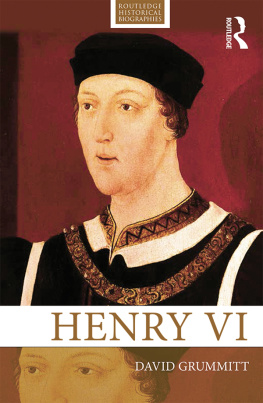

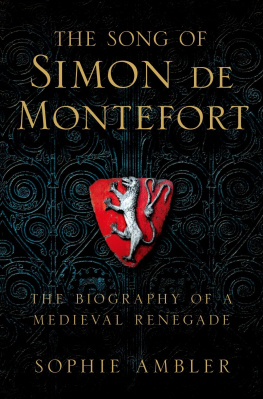

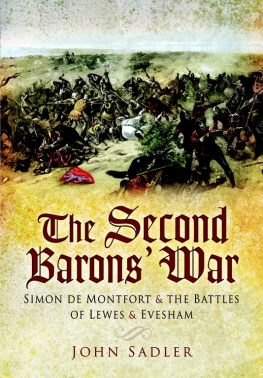

The Disinherited were political rebels in England who defied King Henry III (r. 121672) for two years after the Battle of Evesham in 1265. They were so-called because Henry deprived them of their lands as punishment for their support of Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, who had held the king prisoner since his victory at Lewes the previous year. The revolt is generally thought to have ended in 1267, but there was a second phase of disturbances from 126974, after Henrys son and heir, the Lord Edward, left England to go on crusade.

There has been no full-length study of the Disinherited since an unpublished thesis in 1959. They are sometimes regarded as an afterthought: William Henry Blaauw, who wrote a detailed account of the war up to Evesham, wearily remarked that it is unnecessary to detail all the scattered hostilities that plagued the kingdom afterwards. Yet the resistance of this large and distinct class of destitute sufferers, as he called them, amounted to a great deal more than a few scattered hostilities. The whole of England was engulfed in conflict, and the legacy of this bitter, protracted war would last for decades.

In political and military terms the war of the Disinherited holds much of interest. The land resettlement after Evesham witnessed confiscation on a massive scale, as royalists were rewarded with forfeit estates or simply took what they wanted. To oppose the kings superior forces, the Disinherited often resorted to guerilla-type warfare, establishing headquarters in wooded and fenland areas. There were few pitched battles, as the rebels concentrated on cutting royal supply lines, as well as burning and pillaging the land. This left many parts of England devastated: nowhere was there peace, nowhere security, as Walter Bower, a fifteenth-century Scottish chronicler, described the state of England at this time. In the end, despite suffering a number of defeats, the Disinherited reached a compromise with the king. The Dictum of Kenilworth, whereby rebels were permitted to buy back their lands, was an admission that the royalists could not hope to end the war by armed might alone.

Many of the Disinherited were unattractive characters, at least by modern standards; they were violent, prejudiced and avaricious, with little respect for human life. Yet these were the flaws of the age. The grit and resource of men who refused to accept the theft of their property, in the face of overwhelming odds, is worthy of remembrance.

Chapter 1

Reform and Rebellion

The background to the revolt was the civil war in England that began in 1259 and ended with the traumatic battle of Evesham, which marked the end of the first phase of the conflict. To understand the Disinherited and their motives, it is necessary to explain the background.

Broadly speaking, the wars in England were triggered by protests against the rule of Henry III. These included the kings alleged financial extravagance, the unpopularity of his Lusignan and Poitevin kinsmen, military reverses in Wales and baronial protests against Henrys doomed effort to place his second son, Edmund, on the throne of Sicily. In 1258 the barons attempted to limit the kings behaviour via the Provisions of Oxford, confirmed the following year by the Provisions of Westminster. The Provisions of Oxford were an effort to control the government via a council of barons, called the Council of Fifteen. These men were to give the king counsel in good faith for the government of the realm, and in all things pertaining to the king and the realm; and to amend and redress all things which they find in need of redress and amendment; to exercise power over the Justiciar and other people.

King Henry swore to accept the decisions of the Council of Fifteen, and ordered his subjects to obey whatever the council should decree. Otherwise nothing could be done in affairs of state, and in all things its word was final.

It did not take long for political tensions to slide into violence. The first serious outbreak occurred in northern England. In 1260 Sir John Deyville, a pugnacious northerner who would later play a leading role among the Disinherited, gathered a company of disgruntled barons and ravaged parts of Yorkshire. The Sheriff of York, Peter de Percy, No further details of this campaign survive, though it shows the basis of Earl Simons support in the north. John and his friends were a tough, close-knit bunch, and it seems Percys efforts to defeat them met with little success. The baronial rebels in the north would cause a great deal of trouble in future years.

There was also trouble in the Welsh March, the buffer zone between England and Wales. This was nothing new, since violence, raiding and private war were the order of the day on the chaotic borderlands. Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (r. 124682), lord of Gwynedd and would-be Prince of Wales, had been attacking crown territory in Wales since 1256; his ultimate goal was to unite the whole of Wales under his banner.

The situation in England deteriorated in the spring of 1263 when Simon returned from France, determined to enforce the baronial reform movement with himself as its leader. There was further chaos in the March where the death in 1262 of Richard de Clare, Earl of Gloucester, removed one of Simons chief rivals. His heir, Gilbert the Red (so-called after his shock of red hair and fiery temperament), refused to swear loyalty to the Lord Edward when ordered by Henry III. The new earl was a more radical character than his father, and may have taken a strong personal dislike to Edward.

Meanwhile, Llywelyn pressed hard on royal lands in Gwent, southeast Wales. In March an enormous Welsh host, all the pride of Wales, led by his steward Goronwy ap Ednyfed, marched to the banks of the River Usk. Here they were held for two days by an army of Marcher lords led by Sir John Grey, Roger Mortimer, Reginald FitzPeter and Peter de Montfort. On Saturday 3 March, at midday, the Marchers crossed a ford above the town of Abergavenny and stormed into the flank of