E PILOGUE

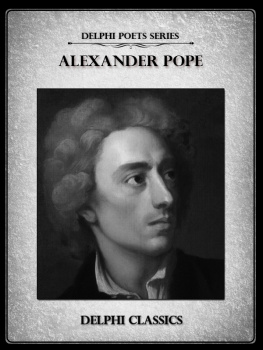

N O one contemplating the convincingly expressive bust that Roubilliac made of Pope in 1758 (now at Temple Newsam), can fail to be charmed by the tremulous modelling of the cheek, the delicate sensuousness of the mouth, framed though it is in lines of suffering. But, he will ask, is there not some hint, somewhere, of combativeness? It is not in the beautiful calm line of the forehead, nor in the thoughtful eyes; the long, shapely nose, seems even in marble to quiver with sensibility. Yet is there not something in the way it is set, about the slight curve at the bridge, that reveals, or at least arouses suspicions of aggressiveness?

Such a quality was perhaps a condition of Popes survival; for mere resignation to the disgrace of his physical being would not have been enough to make his life bearable. Unable to get up or go to bed by himself, strapped up by day in a stiff canvas bodice to keep his frame straight it wasted on one side wearing three pairs of stockings to make his calves look even decently reputable, so easily chilled that he wore a kind of fur doublet beneath a thick linen shirt, and constantly racked by headaches, it is amazing that he should have carried his four foot six of humped humanity with so much cheerfulness, good temper, and benevolence. The fiery bright and dauntless spirit had of necessity to oppose itself actively to fat ease and complacency, to intellectual sloth, or dullness of physical perception; for the sake of its very self, attack the men who harboured these negations.

Regarding him as a social being apart from his existence as an author (Heaven! was I born for nothing but to write?), you are drawn to dwell upon his virtues; first his obvious goodnesses, his help to the struggling to Savage, for example, and even to Dennis in his aged indigence; his innumerable kindnesses to little people, involving a great deal of trouble; his giving more than a tenth of his income to charity, his kindness to wearisome authors whose works he read and improved however much he might bemoan it in the Prologue to the Satires and then you think of something more difficult, his virtue as a companionable human being. Moreover the kind of portent that he was entailed another kind of virtue: he had worked indefatigably to make himself independent; he never had to sell or hire his pen, never write a word he did not want to write, and he was the first author to live by his profession without adulation or fawning or parasitism. He transformed the social position of the man of letters, not because he himself, of comparatively humble origin, came to mix on level terms with the great landed aristocracy, but because he established for the writer a definite place in society: yet he found time to be the warmest-hearted of human beings in daily life. An early essay in the Guardian (No. 61) Against Barbarity to Animals is one of the earliest of statements of humanitarianism (he was closely followed in this by James Thomson), and it was perhaps his own physical weakness, combined with immense nervous vitality, that gave him his deep sympathy with all living things. His fondness for dogs was notorious. His own Great Dane, Bounce, was one of the great pleasures and cares of his life an intelligent creature who wrote an admirable poem to Lady Suffolks lap-dog, Fop; and if kept in her kennel too long, she would when let out leap exuberantly upon Pope and roll him over. A surprising picture! And it was because of his weakness, perhaps, that he liked people who had in them abundance of life, of positive life, of natural goodness as with Bethel and Allen, of large-hearted vitality as in the far from virtuous Bathurst, of intellectual vitality as in his literary friends: the other side of the medal was his striking out viciously, almost you might think with the virulence of fear, at those who opposed life, who lessened its stream, who denied what was positive, pretenders to virtues they had not got.

It is pleasant to think of him in the more genial moments of his life, say at Twickenham in 1726, when, as Bolingbroke reminded him, he sauntered alone with the fallen statesman, or, as we have often done, with good Arbuthnot, and the jocose Dean of St Patricks, among the multiplied scenes of your little garden. It is when he could enjoy the feast of reason and the flow of soul, that he was most himself, whether at his own home entertaining in house or grotto, or with Jervas the painter in London, at Ladyholt with Caryll, or visiting his great friends at Stowe or Cirencester or Hagley, or perhaps steering the frail bark of his body to careen at Bath with Gay. The amount of travel he did in his latter years was astonishing; he seems never to have been still, and though always visiting, ever writing. Yet while his mother lived he felt tied by her possible needs, and would never go away without consideration for her well-being.

But, as we have seen, in that decade other deaths made him lonelier, and his vigour began to ebb. He had indeed in fragmentary form a further Horatian poem, One Thousand Seven Hundred and Forty, which he might finish it would, of course, become something else if death did not overtake him first. Of his old literary group none were left available to encourage and to laugh, their place being taken by the blundering but reassuring Warburton the most impudent man alive, Bolingbroke called him who usurped the place posterity would wish Spence to have held. Added to his usual ills and ailments, asthma came to torture his nights still further. He had for years been an ill sleeper, declaring in his first satire:

I think,

And for my soul, I cannot sleep a wink.

I nod in company, I wake at night,

and indeed he carried nodding in company to such lengths that he slept when the Prince of Wales, then head of the opposition faction, came to dine, though it is only fair to add that Frederick was at the moment discoursing of poetry. The valetudinaire was, alas, no longer gay, but a trial to the servants of his friends, though those who looked after him had no cause to complain of his meanness. He came to rely more and more upon the presence of Martha Blount, and his eye would always light up when he saw her approach. She came indeed

to figure more in his life than was agreeable to his friends, and when in 1743 together with Pope she visited the Allens at Prior Park, Mrs Allen as good as turned her out of the house. Perhaps she presumed too much; but after all, was anybody so devoted to Pope as she was? In revenge she was the cause of his polluting his will with female resentment as regards the Allens.

It was in this year that he seems to have felt his end approaching, for he then made his will, leaving most of his goods to Martha Blount, and the copyright of his work to Warburton; as he broke up it was Bolingbroke and Marchmont who were his main contact with the outer world. Yes, he wrote to them,

I would see you as long as I can see you, and then shut my eyes upon the world as a thing worth seeing no longer. If your charity would take up a small bird that is half-dead of the forest, and set it a-chirping for half an hour, I will jump into my cage, and put myself into your hands to-morrow at any hour you send. Two horses will be enough to draw me (and two dogs if you had them).

About three weeks before he died he sent copies of his Ethic Epistles to his friends, commenting: Here I am, like Socrates, dispensing my morality amongst my friends just as I am dying. He was serene enough, not doubting of a future existence, feeling the souls immortality within him, as though by intuition.