MY DEAR SON: WE HAVE learned that your Worthiness, forgetful of the high office with which you are invested, was present from the seventeenth to the twenty-second hour, four days ago, in the Gardens of John de Bichis, where there were several women of Siena, women wholly given over to worldly vanities. Your companion was one of your colleagues whom his years, if not the dignity of his office, ought to have reminded of his duty. We have heard that the dance was indulged in, in all wantonness. None of the allurements of love were lacking, and you conducted yourself in a wholly worldly manner. Shame forbids mention of all that took place, for not only the things themselves but their very names are unworthy of your rank. In order that your lust might be all the more unrestrained, the husbands, fathers, brothers and kinsmen of the young women and girls were not invited to be present. You and a few servants were the leaders and inspirers of this orgy. It is said that nothing is now talked of in Siena but your vanity which is the subject of universal ridicule. Certain it is that here at the baths, where churchmen and the laity are very numerous, your name is on every ones tongue.

The words are taken from an admonitory letter of Pope Pius II to Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia better known to the world as Pope Alexander VI written in June, 1460, when the young cardinal had not yet reached the thirties, and reproving him for having arranged a bacchanalian feast in Siena. No words could better characterize the personality of Alexander VI, for they show him as the man of the world he was as Cardinal Borgia and remained after he had become Pope Alexander.

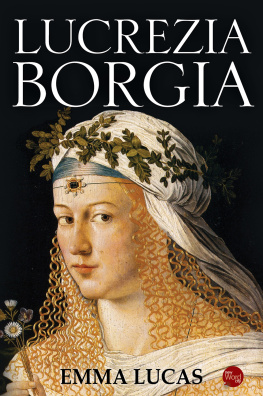

The limelight of history has played in a rather oblique and unkind way on the Borgias. Pope Alexander personality has been distorted until he became a perfect monster; yet his greatest weakness was an easy freedom from moral scruples, and this might not have blurred his personal charm at all had he not become the tool of his son Cesare. More unjust still were most historians to his daughter Lucretia, who has been depicted as a kind of Messalina, although she was at the best the indifferente among the great women of her time, and at her worst a beauty without any will of her own. If it is the historians task to distribute praise and blame, some of the latter may fall on Alexanders favorite son Cesare. Even if he was not such a perfect virtuoso of crime as he has been described, he certainly was not much better than some of the worst of his more prominent contemporaries.

Thus in considering the rise and fall of the Borgia family one ought to keep in mind that the Borgias were after all the creatures of an epoch, rich in extraordinary personalities as few others in human history have been. Before rendering judgment consideration must be given to the remarkably complex personalities of the Renaissance. The men and women of that epoch of transformation from the middle ages to modern times were so constituted that it was easily possible for them to turn from cruelty and crime and vice, from corruption and treachery, to religion with a fervid and impassioned sincerity. The Borgias, as will be seen, did not differ greatly from many of their contemporaries. To make them the scapegoats of their times shows, perhaps, a just indignation at their crimes, but little understanding of the conditions under which they lived.

Bearing in mind these conditions and the remarkable rise of the House of Borgia, one will be better prepared to understand the personality of Pope Alexander who with all his faults was certainly not without redeeming features. Of his ability, of his genius even, says Bishop A. H. Mathew, one of his recent biographers, there can be no two opinions; indeed if vigor of body and mind were all that was required of a pope, Alexander VI would have been among the greatest. He had a remarkable capacity for hard mental work, and his buoyant, jovial nature enabled him to bear his burden of vice and crime with a lightness impossible to a man of a less sanguine disposition. Such was the complex personality of this typical man of the Renaissance.

A fair estimate of Alexander VI must include in addition to his personal gifts and the complexities of his character a consideration of the remarkable rise of his family. It was from this source that he received a further impetus toward that most seductive of all human temptations the abuse of power. The Borgias like the Bonapartes three centuries later in France were neither an old nor a native family. They had come from Spain where their ancestors had participated in the expulsion of the Moors in the thirteenth century, their family name being derived from their native place of Borjia on the borders of Aragon, Castile and Navarre.

But with the election of one of their family, Alonzo Borgia, as Pope Calixtus III, in the middle of the fifteenth century, they became prominent in the affairs of the European world just at the moment when Italy, then the most advanced country of that continent, had cast off the fetters of medieval envelopment and entered upon the most brilliant period of its cultural development. Calixtus III had been a professor of jurisprudence in Lerida in Spain, where he won the reputation of being one of the foremost jurists of his time. He had come to Rome as a legal adviser to King Alphonso of Naples. His knowledge and character and his extreme age which made it certain that he would not be long in the way of other aspirants to the papal tiara finally secured his elevation to the highest place in Christendom.

In contrast to the other papal elections of the time the nomination of Calixtus III was not accompanied by the sneering remarks which such occasions usually called forth. Although his reign lasted only three years he managed to secure a firm footing for the Borgia family in the Roman hierarchy. He may indeed be considered as one of the initiators of nepotism in the papacy, and the first ruler of the Roman church, who founded a kind of family dynasty through the promotion of his nephews. Two of these, Luis and Rodrigo Borgia (later Pope Alexander VI) became cardinals, while a third who was not a priest was promoted to the captaincy-general of the papal state and created duke of Spoleto. The latter, as prefect of Rome, had also to keep in check the old families of the Colonna and Orsini, the traditional enemies of the papal rule in the Holy City.

While Calixtus III kept on the defensive against his enemies in the city of his residence, he followed the papal tradition of crusading against the Turk. The latter had just taken possession of Constantinople and made it his capital. The power of the Turkish empire was spreading in South-Eastern Europe, and to war against it Calixtus brought great sacrifices, selling the jewels of the papal treasury and other possessions of the Church. For another and greater phenomenon of his time, the Renaissance in Italy, Pope Calixtus had no understanding. The humanists complained that he never gave them a helping hand, and that he even sold the precious golden bindings of Greek manuscripts in order to finance his expeditions against the Turks. The successors of Calixtus III held other views. Literature and the arts flourished under their patronage. Painters and sculptors, writers and savants, thronged the papal Court. This intrusion of scantily disguised agnosticism into the heart of the church frightened the pious and the conservatives who heard the first rumblings of the Reformation. Paul II restored the pagan monuments of Rome, and, after the Medici of Florence, was the greatest collector of the time. The successor of Paul, Sixtus IV, went even further. The principal result of his reign was the secularization of the papacy. For Sixtus IV was a worldly prince in the full sense of the word. The aim of his policy was not even the extension of the power of the Holy See, but primarily the enrichment of his relatives and favorites. With his approval the Medici were murdered by the Pazzi family, a design which could not be accomplished completely and which finally reacted to the disadvantage of the Pope himself. There was an increasing demand for a council which should depose this ruler of the church without religion and conscience who was called the Pope; a pious poet of the time wailed over the fact that everything was at sale in Rome: Temples, priests, altars and even prayers, heaven and God. In August, 1484, Sixtus died, at the age of seventy, a martyr to gout and worn out with rage at the news of the peace which had been made between the Duke of Ferrara and the Venetians without his consent.