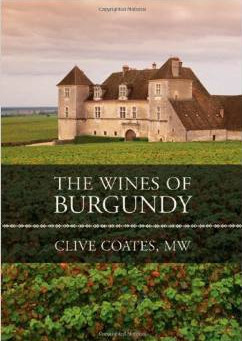

T he sun over Burgundys seemingly endless expanse of richly green vineyards belonged to late summer. What few clouds there were, were fantastical, fat, and luminousgiant dollops of silver and white acrylic paint that had not yet finished drying onto Gods vast canvas of sky. Plush canopies of leaves on the tens of thousands of vines fluttered in breezes so faint that if not for the subtle sway it would have appeared there wasnt any breeze at all. Chirping sparrows swooped every which way, as if theyd spent the night drinking from an open barrel in one of the nearby cuveries. With the gentle rise and fall of the terrain, the vineyards resembled a slow rolling ocean of unpredictable currents.

The temperature that September morning in 2010, in the Cte dOr region, which is the heart of Burgundy, and for many serious wine collectors the only part of Burgundy that matters, was already well on its way to sweltering. The humidity was as present as a coastal mist. Soon, the workers would spill from the villages to tend to the vines. The enjambeurs would arrive: The spider-shaped tractors, with their high tires to easily traverse the meticulously ordered vine rows, would scurry about dodging the tourists bicycling along the narrow ribbons of dirt road between the vineyards. For the moment, however, the landscape was quiet; as far as the eye could see the only person among the vines was the Grand Monsieur.

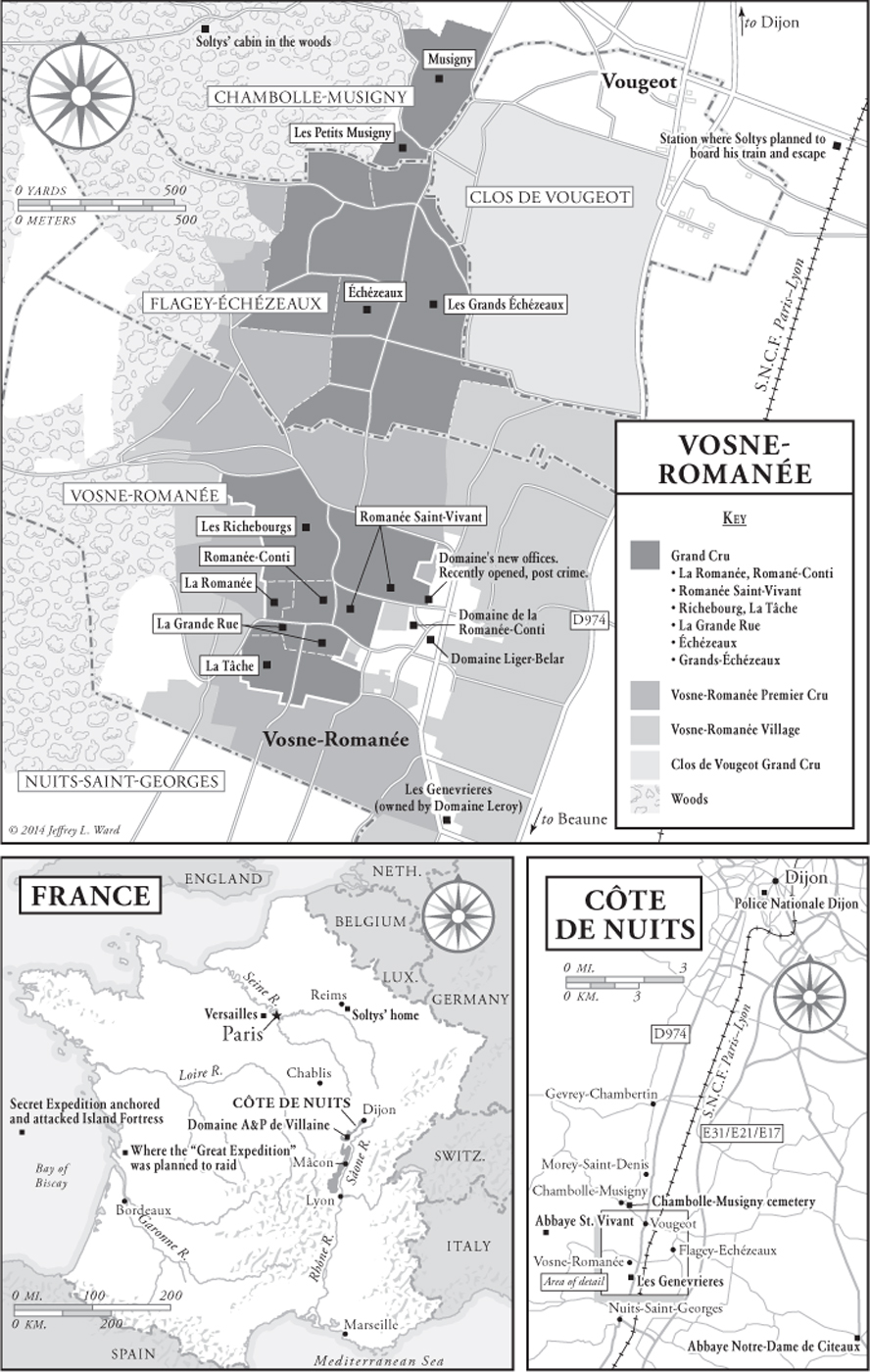

Dressed in shades of khakieven his wide-brimmed, cloth hatseventy-one-year-old Aubert de Villaine walked in the parcel called Romane-St.-Vivant. Tall and thin, he waded through the vines as he had done for more than four decades: in bursts of long strides, arms out slightly from his sides, palms skimming the vine tops.

Every so often he would stop, fish the handkerchief from his pocket, wipe the perspiration from his brow, and look about. Monsieur de Villaine knew that everything and nothing was unfolding before his eyes, and that it was his challenge to determine which was the everything and which was the nothingto find the clues in natures mystery.

At moments like this, surrounded by the sublime splendor of the vineyards before the harvest, the Grand Monsieur sometimes thought of the French mastersPissarro, Renoir, Monet. He suspected they would have appreciated Burgundy and understood his work.

One must have only one masternature, Pissarro had said. Renoir had put it this way: You come to nature with your theories and she knocks them all flat. And Monetah, Monet. Was it any wonder he described it best of all? A landscape hardly exists at all as a landscape because its appearance is changing in every moment. But it lives through its ambiance, through the air and light, which vary constantly.

Though Monsieur de Villaine would have insisted he was unworthy of such a comparison, he had much in common with Monet. When Monet first picked up his brush he saw and painted the natural world in pieces. He put the water here and the sky there; the field went here; flowers and trees went here, here, and there. Each was an element unto itself, existing almost independent of its surroundings, as if, just like that, any one of the elements could have just as easily been placed in another scene, transported to another painting.

As he matured, however, Monets work became less technical and more organic, spiritual. He came to understand natures power. It was as if one day, while standing alone on the banks of that pond covered in water lilies, Monsieur Monet discovered a crease in the universe, pulled it open like curtains, stepped inside, and turned and viewed the world from another dimensionfrom a perspective that allowed him to see the interconnectedness of it all, to see the light and air, and the flicker and flow of energy among all natural things.

It was then that Monet began to make the invisible visible. The lines he had once thought defined and separated some natural order dissolved into a liquefied oneness, filling the canvas for others to drink in, and, if only for a few moments, to experience the divine.

This was what the Grand Monsieur labored to do. Only with grapes. His life had been dedicated to transcending the technical and vinifying natures invisible energy.

As he studied the masterpiece of the landscape around him, the Grand Monsieur prayed for a sign. He prayed although he wasnt as confident in the power of prayer as he once had been. Because of recent horrific events and the possibility of unsettling outcomes, the Grand Monsieur had begun to question Gods very existence.