PROUST

Proust

The Search

BENJAMIN TAYLOR

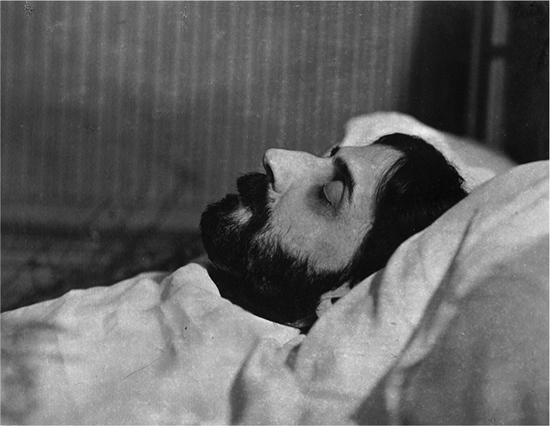

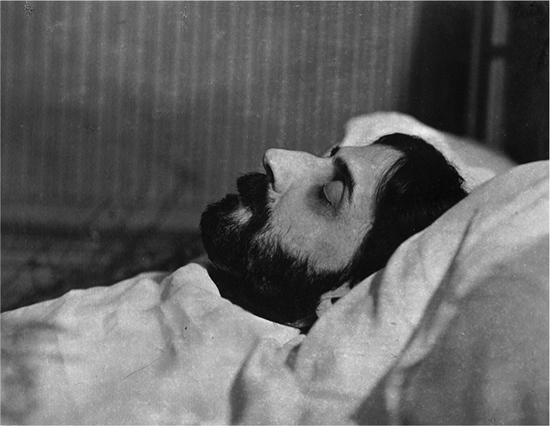

Frontispiece: Man Ray, Proust on his deathbed. Man Ray Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris; RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY.

Copyright 2015 by Benjamin Taylor.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Janson Oldstyle type by Integrated Publishing Solutions.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015935549

ISBN 978-0-300-16416-9 (cloth : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Credits appear on , which constitutes a continuation of the copyright page.

IN MEMORY OF JAMES MERRILL

Too violent,

I once thought, that foreshortening in Proust

A world abruptly old, whitehaired, a reader

Looking up in puzzlement to fathom

Whether ten years or forty have gone by.

Young, I mistook it for an unconvincing

Trick of the teller. It was truth instead

Babbling through his own astonishment.

The Book of Ephraim

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

M AN R AYS CELEBRATED PHOTO of Marcel Proust on his deathbed shows a youngish-seeming man with ringed eyes and bedclothes pulled up to his chin. Jean Cocteau had summoned Ray to 44, rue Hamelin to take the final picture. Left alone briefly with the body that afternoon, Cocteau noted the vast manuscript of In Search of Lost Time on the mantelpiece of the bedroom: That pile of papers on his left was still alive, like watches ticking on the wrists of dead soldiers. The date was November 18, 1922.

Death of the artist, lastingness of the work: One thinks of Prousts description in The Captive, the fifth volume of In Search of Lost Time, following the death of Bergotte, the cycles great novelist figure, of certain bookstore windows: The idea that Bergotte was not permanently dead is by no means improbable. They buried him, but all through that night of mourning, in the lighted shop-windows, his books, arranged As with Shakespeare, as with Balzac, as with the fictional Bergotte, fifty years and a little sufficed Marcel Proust for the completion of an ever-living imaginative universe. The million-and-a-half-word masterpiece that was, from 1909, his sole reason for living makes as large a claim on our attention as any literary work of any era. Prousts Search is the most encyclopedic of novels, encompassing the essentials of human nature. His cumulative breadth of understanding, in what is ostensibly a narrative of modern French life, extends to every dimension: familial, social, amatory, intellectual, artistic, religious. His account, running from the early years of the Third Republic to the aftermath of World War I, becomes the inclusive story of all lives, a colossal mimesis. To read the entire Search is to find oneself transfigured and victorious at journeys end, at home in time and in eternity too.

A biographer of Proust must begin with the following reversible axiom: The work is not explained by the life; the life is not explained by the work. All Prousts transactions between real life and its dramatization are in the care of the shape-shifting imagination, a creative not a recording capacity. Actual persons do not explain any of the characters on whom they are said to be based. Laure Hayman does not explain Odette de Crcy; Robert de Montesquiou does not explain the Baron de Charlus; neither Charles Haas nor Charles Ephrussi explains Charles Swann; Bertrand de Fenlon does not explain Robert de Saint-Loup; Albert Le Cuizat does not explain Jupien; neither the Comtesse lisabeth Greffulhe nor the Comtesse Adhaume de Chevign explains Oriane de Guermantes. Still less does the historical individual named Valentin Louis Georges Eugne Marcel Proust, born to a French Jewish mother and French Catholic father in July of 1871, explain the Narrator of the Search. Nabokov puts the matter succinctly: Prousts book is not a mirror of manners,

Above the dung heap of real life, art hoists its flag. That memorable metaphor occurs near the end of the Search, a 3,300-page epic telling of how a frightened tadpole grows up to be an omnipotent artist. Prousts book is, as Howard Moss writes, its own self-sealing device: Our hero sits down at the end of the tale to write the book we have just finished reading.fleurs (1918); growing fame, declining health; the struggle to finish and to correct proofs; the final emendations; the death.

At the midpoint of this life, ramifying every which way, was the Dreyfus Affair. In November 1894 a captain of the French army and Alsatian Jew named Alfred Dreyfus, falsely accused of selling military secrets to the Germans, was convicted and transported to Devils Island to serve a life sentence. The subsequent trial and acquittal two years later of Esterhazy, the actual traitor; Zolas broadside Jaccuse !; the Captains return from French Guiana in 1899 to stand trial a second time; his eventual exoneration in 1906all these are strongly present in the Search, and at every social level. One example, from among hundreds, must suffice here: In The Guermantes Way, coming home from having witnessed a quarrel between Bloch, the Narrators obnoxiously erudite Jewish friend, and M. de Norpois, a grandee of the Foreign Ministry, on the subject of Dreyfus, our hero overhears his familys butler, who is Dreyfusard, arguing with the Guermantes butler, who is anti-Dreyfusard. Thus the Affair has riven France across all classes, as well as coining the idiom for antisemitic campaigns to come.

The Jews of the Search are of every moral stripe andglory of the novelof stripes that change. About Swann when he is dying, Proust writes in Sodom and Gomorrah: Perhaps, too, in these last days, the physical type that characterizes his race was becoming more pronounced in him, alongside a sense of moral solidarity with the rest of the Jews, a solidarity which Swann seemed to have forgotten throughout his life, and which, one after another, his mortal illness, the Dreyfus case and the anti-Semitic propaganda had reawakened. There are certain Jews, men of great refinement and social delicacy, in whom nevertheless there remain in reserve and in the wings, ready to enter their lives at a given moment, as at the theater, a boor and a prophet. Swann had arrived at the age of the prophet.their relation to what they thought they knew and held dear, and gives them the lasting sense that something atavistic has stepped into the open. Had he lived into the 1950s, Proust would have appreciated the postwar quip about going back in time to report to our pious forebears that an enlightened European people famed for philosophy, science, art, music, and poetry would one day rise up to destroy the Jews. Those French are capable of anything, our forebears would surely have responded.

Prousts life is, like his book, a series of self-transformations; but not a series you can know from the

Next page