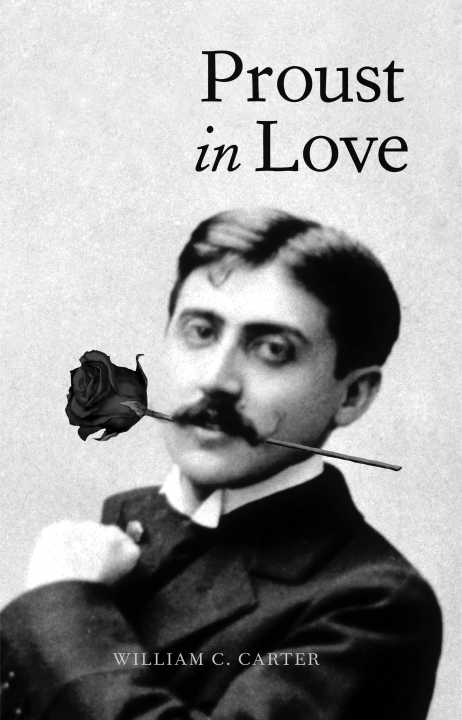

Proust

in Love

Proust

in Love

WILLIAM C. CARTER

For Josephine and Terence Monmaney, who, through Proust, found love

Love alone is divine.

-Marcel Proust

Contents

ix

xi

xiii

Acknowledgments

I wish to express my sincere thanks to those who encouraged me in the research, writing, and production of this book. The list of those to whom I am deeply and happily indebted includes Robert Bowden; Elyane Dezon-Jones; Anne-Marie Bernard; Marie-Colette Lefort; Robert Blumenfeld; Bob Borson; the late Dr. L. M. Bargeron Jr.; J. P. Smith; Claudia Moscovici; Caroline Szylowicz, Kolb-Proust Librarian at the Kolb-Proust Archive for Research, University of Illinois Library; my friends and colleagues at the University of Alabama at Birmingham's Mervyn H. Sterne Library; my editors at Yale University Press, John Kulka and Dan Heaton; and, as always, and especially, my wife, Lynn.

Introduction

Proust in Love portrays the novelist Marcel Proust's amorous adventures-and misadventures-from his adolescence through his adult years, applying, where appropriate, his own sensitive, intelligent observations about love and sexuality, which are often disillusioned and at times highly amusing. These observations are drawn from his correspondence, his novel In Search ofLost Time, and his other writings.

Proust's achievement is unique in a number of ways. Widely recognized as one of the world's great novelists, he wrote only one novel, but one of vast proportions, consisting of seven principal parts whose English titles are Swann 's May, Within a Budding Grove, The Guermantes May, Sodom and Gomorrah, The Captive, The Fugitive, and Time Regained. The central figure, who tells us his life's story in the first person and whose enchanting voice we come to know intimately, never identifies himself with a name. We refer to him simply as the Narrator.

Proust in Love inevitably contains some overlap of material covered in my recent biography Marcel Proust: A Life, but I focus here on the links between Proust's amorous relationships and his transposition of these into the Narrator's erotic experiences and his depictions of a variety of sexual types, particularly homosexuals and bisexuals. I have tried to avoid weighing down the book with too many academic analyses, but in the notes I do refer the curious reader to those works that I consider most useful in probing the various critical and psychological interpretations of Proust's ideas about love and sexuality.

The new Forssgren documents- The Memoirs of Ernest Forssgren, Proust 's Swedish Valet (Yale University Press, 2006) and Paul Morand's recently and posthumously published private diary, Le Journal inutile (The useless diary), available only in the original French edition-add interesting details to the portrait of Proust in love and provide new glimpses of his modus operandi when attempting to seduce young men from the servant class. Morand was a young writer and diplomat who met Proust in 1916. He and his future wife, Princess Helene Soutzo, quickly became part of Proust's intimate circle of friends and remained closely associated with him until his death.

It is clear from the memoirs of those who knew Proust, his letters, testimony by witnesses, and scenes from the novel that the vicious, sadistic side of sexuality intrigued him. Whether he participated in such acts or merely observed them, it is certain that the dark side of passion both attracted and repulsed him. Indeed, jealous, obsessive, and sometimes sadistic love is a profane theme that runs throughout Proust's novel in direct counterpoint to the transcendent, sacred theme of art, which ultimately triumphs as the Narrator concludes his quest. Along the way, Proust brilliantly portrays and analyzes the manifestations of such love in the heterosexual couples Swann and Odette, the young Narrator and Gilberte, the mature Narrator and Albertine, and Robert de Saint-Loup and the actress Rachel, and in homosexuals such as Mlle Vinteuil and her friend (a key figure, but one with no name), Charlus and Charlie Morel, and the bisexual lovers Saint-Loup and Morel. In spite of the dark, anxious overtones issuing from the bitter experiences of jealous, disappointed lovers, Proust often brings to bear his trenchant wit or mischievous sense of humor as he delights in showing how frequently and how thoroughly love makes fools of us all.

Abbreviations of Titles of Proust's Works

All quotations from In Search of Lost Time are from the Modern Library Edition in 6 volumes, translated by C. K. Scott Moncrieff and Terence Kilmar- tin, revised by D. J. Enright, New York, 1992. Each section of the novel is cited by its title, volume number, and page number:

1. Swann's Way

2. Within a Budding Grove

3. The Guermantes Way

4. Sodom and Gomorrah

5. The Captive and The Fugitive

6. Time Regained

The following abbreviations are used for the correspondence and miscellaneous writings of Marcel Proust:

For those works and documents that exist only in French, all translations are my own, unless otherwise indicated.

Proust

in Love

CHAPTER ONE

Promiscuous Proust

The principal trait of my character: The need to be loved and, to be more precise, the need to be caressed and spoiled even more than the need to be admired.

Marcel Proust attended high school at the lycee Condorcet from 1882 to 1889. Among his "intimate circle" of classmates were an astonishing number of future writers. Daniel Halevy wrote biographies of Friedrich Nietzsche, Jules Michelet, and Sebastien Vauban; Louis de La Salle, who died young, published a volume of poetry and a novel; Robert Dreyfus became an important historian of the Third Republic. Two other high school friends, the poet Fernand Gregh and the playwright Robert de Flers, were elected to the Academie Francaise, an honor not bestowed upon Proust, whose belated achievement as a novelist was to eclipse those of his brilliant schoolmates.

Proust's classmates did not always enjoy his company. His obvious literary gifts awed them, but his personality, especially his jealous need for their exclusive attention, often repulsed them. Jacques-Emile Blanche, who painted a famous oil portrait of Proust, recalls in his memoirs a mutual childhood friend who confided that whenever he played with the future writer, he was always "gripped with fear when I felt Marcel seize my hand and declare to me his need for total and tyrannical possession."' With the callousness common to adolescent boys, Proust's classmates teased and snubbed their sensitive and clinging companion, curtly rejecting his offers of greater intimacy, thus wounding him deeply.