The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

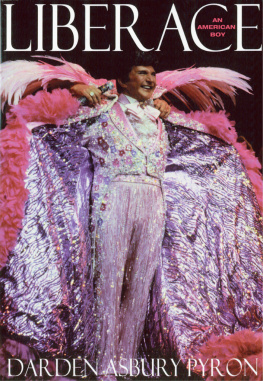

2000 by Darden Asbury Pyron

All rights reserved. Published 2000

Paperback edition 2001

Printed in the United States of America

09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 01 2 3 4 5

ISBN: 0-226-68667-1 (cloth)

ISBN: 0-226-68669-8 (paperback)

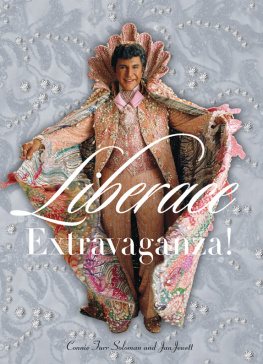

Frontispiece courtesy of the Liberace Foundation, Las Vegas, NV. The Liberace Foundation, founded by Liberace in 1976, is a non-profit organization providing scholarships for students in the performing and creative arts. For a list of funded schools or grant guidelines, please write to the Liberace Foundation at 1775 East Tropicana Avenue, Las Vegas, NV 89119.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Pyron, Darden Asbury.

Liberace : an American boy / Darden Asbury Pyron.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p.) and index.

ISBN 0-226-68667-1 (acid-free paper)

1. Liberace, 1919 2. PianistsUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

ML417.L67 P97 2000

786.2092dc21

[B] 99-08931

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Liberace

AN AMERICAN BOY

Darden Asbury Pyron

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS

CHICAGO AND LONDON

This book is dedicated to my mother, Jo Scott Pyron,

and to the memory of my grandmother,

Marian Asbury Pyron (18921972).

PREFACE

This is not the book I first imagined writing.

In mid-November 1991, I was stranded in Washington, D.C., for a day. Rummaging around the remainder section of a local bookstore, I encountered Scott Thorsons memoir of his years as Liberaces lover. I remembered a little of Liberace from his television days when I was a boy, and I recalled only the headlines of Thorsons palimony suit against the entertainer. The books revelations intrigued me. I flipped to the photographs. They included images of Thorson before and after he underwent plastic surgery to make him resemble his patron. The longer I stared, the more bizarre the episode seemed. I wondered what Liberace could have been thinking; I also reflected on the plastic surgeon who had performed the operation, and on the society that encouraged such transformations. These questions inspired the first idea of a Liberace biography in my mind. I composed some more questions and determined that I could put together a quick, hard little study before I went on to more serious subjects. It didnt work out that way.

The more I reflected on the subject, and the deeper I dug into the data, the more complicated the Liberace problem seemed to become. While the peculiarities, even anomalies, of Liberaces private life had first piqued my interest, other issues soon competed for my attention. Increasingly, Liberace seemed to me a kind of emblem of modern America, overflowing with both the virtues and the vices of the contemporary national character. I began imagining him as the American Boy. Even so, his sexual peculiarities became more glaring as I continued my research. Paradoxically, as he became more and more representative, he grew increasingly less typical. I made my own resolution to the conundrum. It seemed that his homosexuality encouraged his campy artificiality; the campiness, in turn, encouraged the caricature, in life and art, of the American dream. The anomalies, then, became the very sources of his representativeness.

The simple little book I had imagined was no longer so simple. What I envisioned as a three-year commitment, from beginning to end, stretched on and on. But other difficulties complicated the work. Few fellow academics and, more critically, fewer presses shared my enthusiasm for the project. With a small number of notable exceptions, like my old book-reviewing friend from the Miami Herald, Bill Robertson, folks were mostly incredulous that Ior anyone, for that matterwould devote serious attention to such a character. My faithful agent, Jonathan Dolger, was hard pressed to find a publisher willing to consider even the prospectus. He offered his own take on publishers skepticism: he suspected the prejudice of even gay editors. What does a dead, closeted queen performer, adored by Midwestern grannies (as the actor Tony Perkins called Liberaces audiences) have to say to contemporary gay men? Not much, came the answer. That his life might speak to others seemed incomprehensible.

Other problems arose in the writing that had nothing to do with publishers skepticism. Sometimes the project seemed as incredible to me as it appeared to editors. Reading Liberaces memoirs regularly prompted this response. Their syrupy tone, coyness, and evasions grated, sometimes furiously, on my nerves. Formal criticisms of the showman exacerbated my own misgivings. The harshest depict the pianist as nothing less than a cultural demon and a sexual monstrosity. He undermined the highest standards of taste, even while he broke down traditional sexual or gender boundaries, ran the complaints. The criticisms, even the most violent, like Howard Taubmans scathing 1954 critique in the New York Times or William Conners 1956 broadside in the London Daily Mirror, contain truth. Criticism of the showman continues over a decade after his death. The cudgels are wielded now, paradoxically perhaps, by gay writers instead of by his old enemies among the sexually orthodox.

I was not unsympathetic to the biases. Insofar as the criticisms identified the entertainer as a womanish, lower-class, consumer sissy who corrupted art (and maybe the youth of America), I was not eager to justify, much less identify with such a figure. If the queer stuff doesnt get you, the class and cultural angle willalthough as the academic critic Kevin Kopelson has noted, the two can be inextricably combined. I dealt with the difficulty in part by trying to objectify the critics, much as I sought to objectify Liberace himself. This led, however, to other complications in the conceptualization of the project, as I began reflecting on the nature of twentieth-century American culture. A short book was developing into a mighty long manuscript.

Other problems complicated the original plan. From beginning to end, confirming sources, facts, and data proved particularly difficult. Unlike Margaret Mitchell, the subject of my previous project, for which I could consult extraordinarily rich literary documentation, Liberaces life has been extremely difficult to pin down. In some cases, confirming the most basic informationwhen he was living where, for examplewas hard or impossible. The question of where he was living with whom is, obviously, more problematical still. He confessed his own weakness regarding dates, and his chronologies sometimes make no sense. He also dated various episodes in his life differently at different times. Beyond this, Liberace was notoriously secretive, and he revealed little that he did not want revealed. His memoirs leave out much. At least as much as any memoirist, perhaps more, he shaped events both consciously and unconsciously to fit his own image or sense of things. He left almost no private literary sources to check against the public imagery.

Liberace manipulated journalists and newsmen no less assiduously than he did his fans and readers. Insofar as newspapers provide major sources of data about his life, this material is, then, suspect, too. Journalistic sources produced other problems. If the data from standard, establishment newspapers like the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel and the Washington Post come with a spin, making sense of the tabloids stories poses yet more difficulties. But papers like the Globe, the Star, and the National Enquirernot to mention the sensational scandal rags like

Next page