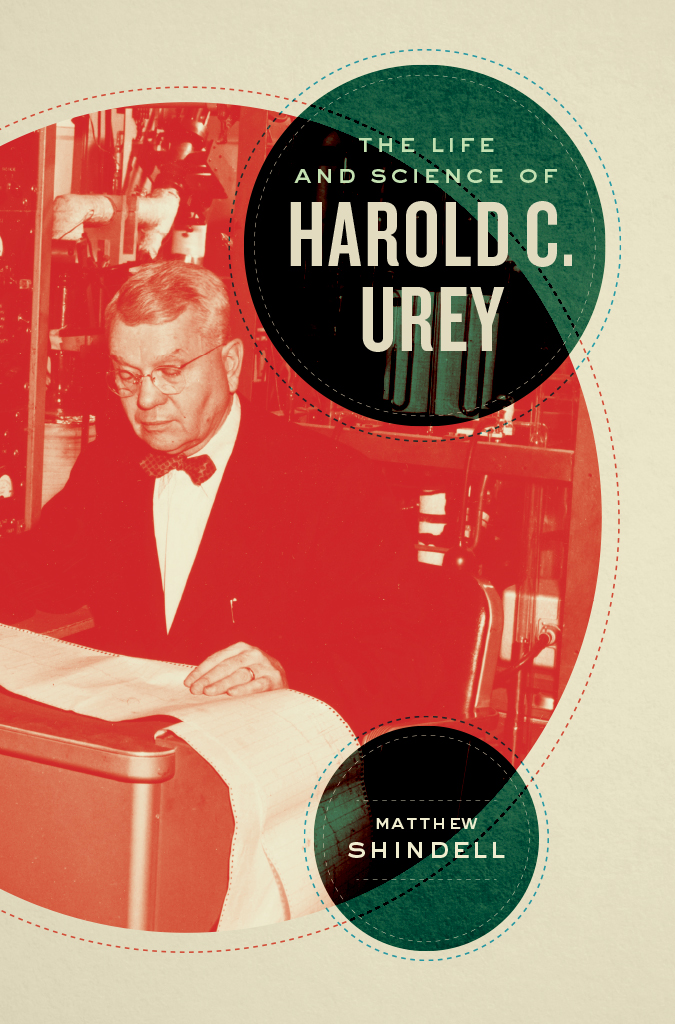

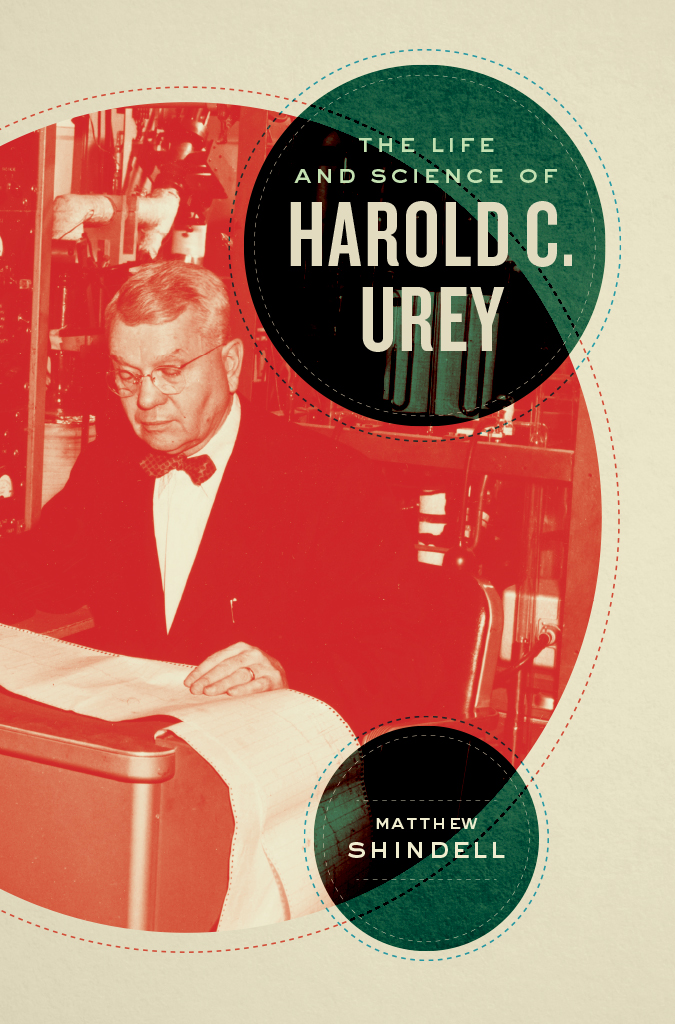

The Life and Science of Harold C. Urey

A series in the history of chemistry, broadly construed, edited by Carin Berkowitz, Angela N. H. Creager, John E. Lesch, Lawrence M. Principe, Alan Rocke, and E. C. Spary, in partnership with the Science History Institute

The Life and Science of

HAROLD C. UREY

Matthew Shindell

The University of Chicago Press Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2019 by The Smithsonian Institution and Matthew Shindell

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2019

Printed in the United States of America

28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-66208-4 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-66211-4 (e-book)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226662114.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Shindell, Matthew, author.

Title: The life and science of Harold C. Urey / Matthew Shindell.

Description: Chicago : University of Chicago Press, 2019. | Series: Synthesis | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019025459 | ISBN 9780226662084 (cloth) | ISBN 9780226662114 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Urey, Harold Clayton, 18931981. | ChemistsUnited StatesBiography.

Classification: LCC QD22.U74 S55 2019 | DDC 540.92 [ B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019025459

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Contents

The Making and Remaking of an American Chemist

On Thanksgiving Day 1931, Frieda Daum Urey sat down with her two young daughters and a few invited guests to a holiday dinner in the Manhattan apartment she rented with her husband, Harold. The meal would have to start without him. He had been with them earlier in the day, when she and the girls went to the Macys Thanksgiving Day Parade. Harold was an associate professor of chemistry at Columbia University, and his lab was only a few blocks from their home on Claremont Avenue. On their way to the parade route, he had stopped to check on an experiment. As was often the case, he could not take his mind off his scientific work. The marching bands and outlandish parade balloons did not interest him. Frieda, who had trained as a bacteriologist, understood the scientific life and its demands from firsthand experience. In five years of marriage she had witnessed his uncanny ability to lose track of time when he concentrated on a problem. It was as though he could shut out the world entirely. Now, well past dinnertime, Frieda knew that she had once again lost him to his laboratory. But this evening, which began with such a familiar disappointment, ended in triumph. When Harold did eventually come home, he exclaimed as he entered, Frieda, we have arrived!

Indeed, they had arrived. With the help of his collaborators, Ferdinand G. Brickwedde and George M. Murphy, Harold C. Urey had experimentally proved the existence of an isotope of hydrogen with mass 2. It was an isotope that until then had been considered either unlikely to exist or too rare to detect. He had succeeded in producing a concentrated Isotopes of any given element were supposed to differ from one another only in atomic weight. But heavy hydrogen behaved physically and chemically almost as though it were a different element altogether, and concentrated heavy water molecules containing the isotope also exhibited unique properties. This prompted Urey and his collaborators, in an unprecedented move, to give the isotope a name: deuterium.

The discovery of deuteriumregarded by one commentator as the bonne bouche of inorganic chemistry For the Ureys, it was the American dream come true in the middle of the Great Depression.

The press took notice of Ureys success and decided that America had arrived, too. Prior to the announcement that Urey would receive the Nobel, the British physicists Ernest Rutherford and Francis Aston congratulated him on being a brave experimenter and remarked on how quickly he and his American colleagues had proceeded in researching this new form of hydrogen.

He was neither the first American scientist, nor even the first American chemist, to win the Nobel Prize. Two American chemists, Theodore Richards and Irving Langmuir, the physicists Robert A. Millikan and Arthur H. Compton, and the biologist Thomas H. Morgan, had already been honored. Still, observers saw Ureys achievement as particularly symboliche was one of the first chemists of international renown who had been trained almost entirely in the United States by American talent.

Urey seemed a torchbearer for a new generation of homegrown scientists. By the New York Times assessment, he and his less famous contemporaries signified nothing less than the rebirth of science in the New World; the young members of the American scientific elect, who made their homes in newly founded institutions of science in New York, Chicago, Berkeley, and Pasadena, were pioneers who [gave] an impetus to physical science greater even than that which it felt in the romantic days of Faraday, Maxwell, Kelvin, Liebig and von Helmholtz. The scientists were the inheritors of a great European tradition, but also the American pioneer spirit.

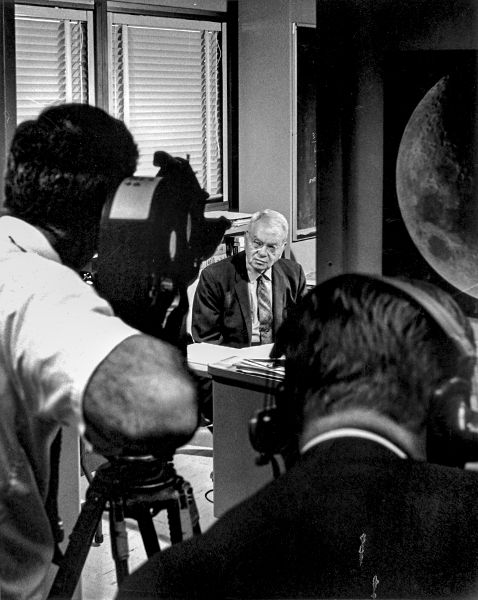

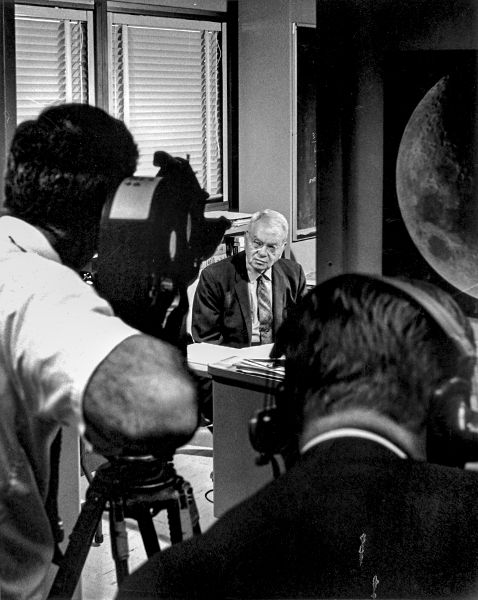

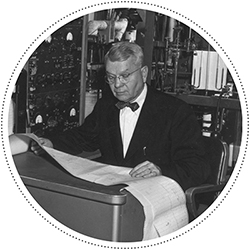

Figure 1 Urey being filmed in his office at the University of California, San Diego. Urey was the most eminent scientific advocate for NASAs lunar science program. Courtesy of the Mandeville Special Collections Department, University of California, San Diego.

Or So the Story Goes...

Given the significance that American commentators placed on Ureys success, it is fitting that the discovery that won him his fame took place on that very American holiday, Thanksgiving. And, just as the story of that day is more complicated than it at first appears, so too is the story of Harold C. Urey. His life and career put him at the center of the most significant scientific moments of the twentieth century; he garnered sciences highest honors; and he became a symbol and a spokesman for American scientific authority. He studied quantum physics in Copenhagen with Niels Bohr, did groundbreaking work with isotopes at Columbia University, ran one of the Manhattan Projects uranium isotope separation laboratories during World War II, moved to the University of Chicago, argued alongside Albert Einstein for the control of atomic weapons, helped found an institute of nuclear studies, transformed himself into an isotope geochemist, helped a graduate student perform the first successful experiment on the origin of life, and took on the origin of the Moon and planets in NASAs space science program. But who was he?

There was a public version of Urey. After winning the Nobel, it was difficult for him to escape the public eye. Not only were excerpts from his public addresses reprinted in the

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).