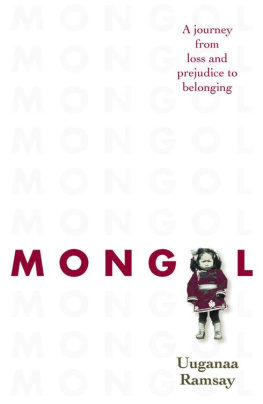

I N MY HAND , Ive got a piece of paper. Its Mums handwriting, and its a lista very long listof all the places we lived until I left home. I look at this list now, and there are just so many of them. My eye moves down the page, trying to take in her spidery scribble, and I soon lose track. These places mean very little to me: its funny how few of them I can remember. In some cases, I guess thats because we were hardly there for more than five minutes. But in others, its probably more a case of trying to forget about them as soon as possible. When youre unhappy in a place, you want to forget about it as soon as possible. You dont dwell on the details of a house if you associate it with being afraid, or ashamed, or poorand as a boy, I was often afraid and ashamed, and always poor.

Life was a series of escapades, of moves that always ended badly. The next place was always going to be a better placea bit of garden, a shiny new front doorthe place where everything would finally come right. But it never did, of course. Our family life was built on a series of pipe dreamsthe dreams of my father. And he was a man whose dreams always turned to dust.

I dont think people grasp the whole me when they see me on television or in the pages of some glossy magazine. Ive got the wonderful family, the big house, the flash car in the drive. I run several of the worlds best restaurants. Im running round, cursing and swearing, telling people what to do, my mouth always getting me into trouble. They probably think: that flash bastard. I know I would. But its not about being flash. My life, like most peoples, is about keeping the wolf from the door. Its about hard work. Its about success. Beyond that, though, something else is at play. Is it fear? Maybe. Im as driven as any man youll ever meet. I cant ever sit still. Holidays are impossible. Ive got ants in my pantsI always have had. When I think about myself, I still see a little boy who is desperate to escape, and anxious to please. The fact that Ive long since escaped, and long since succeeded in pleasing people, has made little or no difference. I just keep going, moving as far away as possible from where I began. Where am I trying to get to? I wonderWork is who I am, who I want to be. I sometimes think that if I were to stop, Id cease to exist.

This, then, is the story of that journeyso far. The tough childhood. My false start in football. The years I spent working literally twenty hours a day. My battles with my demons. My brothers heroin addiction. The death of my father, and of my best friend. Im just forty, and it seems, even to me, such an amazingly long journey in such a short time.

Will I ever get there? You tell me.

T HE FIRST THING I can remember? The Barrasin Glasgow. Its a marketthe roughest, most extraordinary place, people bustling, full of second-hand shit. Of course, we were used to second-hand shit. In that sense, I had a Barras kind of a childhood. But things neednt really have been that bad. Mostly, the way our life was depended on whether or not Dad was workingand when I was born, in Thornhill Maternity Hospital in Johnstone, Renfrewshire, he was working. Amazingly enough.

Until I was six months old, we lived in Bridge of Weir, which was a comfortable and rather leafy place in the countryside just outside Glasgow. Dad, whod swum for Scotland at the age of fifteenan achievement that went right to his head, if you ask mewas a swimming baths manager there. And after that, we moved to his home town, Port Glasgowa bit less salubrious, but still okaywhere he was to manage another pool. Everything would have been fine had he been able to keep his mouth shut. But he never could. Sure as night followed day, he would soon fall out with someone and get the sack; that was the pattern. And because our home often came with his job, once the job was gone, we were homeless. Time to move. That was the story of our lives. We were hopelessly itinerant.

What kind of people were my parents? Dad was a hard-drinking womaniser, a man to whom it was impossible to say no. He was competitive, as much with his children as with anyone else, and he was gobby, very gobbyhe prided himself on telling the truth, even though he was in no position to lecture other people. Mum was, and still is, softer, more innocent, though tough underneath it all. Shes had to be, over the years. I was named after my father, another Gordon, but I think I look more like her: the fair hair, the squashy face. I have her strength too: the ability to keep going no matter whatever life throws at you.

Mum cant remember her mother at all: my grandmother died when she was just twenty-six, giving birth to my aunt. As a child, she was moved around a lot, like a misaddressed parcel, until, finally, she wound up in a childrens home. I dont think her stepmother wanted her around, and her father, a van driver, had turned to drink. But she liked it, despite the fact that she was separated from her father and her siblingsit was safe, clean and ordered. The trouble was that it also made her vulnerable. Hardly surprising that she married my fatherthe first man she clapped eyes onwhen her own family life had been so hard. She just wanted someone to love. Dad was a bad lot, but at least he was her bad lot.

By the age of fifteen, it was time for her to make her own way in the world. First of all, she worked as a childrens nanny. Then, at sixteen, she began training as a nurse. She moved into a nurses homea carbolic soap and waxed floors kind of a placewhere the regime was as strict as that of any kitchen. In the outside world, it was the Sixties: espresso bars had reached Glasgow and all the girls were trotting round in short skirts and white lipstick. But not Mum. To go out at all, a late pass was needed, and that only gave you until ten oclock. One Monday night, she got a pass so that she could go highland dancing with a girlfriend of hers. But when they got to the venue, the place was closed. That was when the adrenalin kicked in. Why shouldnt they take themselves off to the dance hall proper, like any other teenagers? So that was what they did. A man asked Mum to dance, and that was my father, his eye always on the main chance. He played in the band there, and she thought he was a superstar. She was only sixteen, after all. And when it got late, and time was running out and there was a danger of missing the bus, all Mum could think of was the nightmare of having to ask the night sister to take her and her friend back over to their accommodation. Then he and his friend offered to drive them back in his car. Well, she thought that was unbelievably exciting, glamorous even. He was a singer. Shed never met a singer before.

After that, they met up regularly, any time she wasnt on duty. When she turned seventeen, they marriedon 31 January, 1964, in Glasgow Registry Office. It was a mean kind of a wedding. No guests, just two witnesses, no white dress for her, and nothing doing afterwards, not even a drink. His parents were very strict. His father, who worked as a butcher for Dewhursts, was a church elder. Kissing, cuddling, any kind of affection was strictly forbidden. My Mum puts a lot of my fathers problems in life down to this austere behaviour. She has a vivid memory of a day about two weeks after she was married. Her new parents-in-law had a room they saved for best, all antimacassars and ornaments. Her father-in-law took Dad aside into that room, and her mother-in-law took Mum into another room, and then she asked Mum if she was expecting a baby.