Spoon measures are level, unless otherwise specified:

1 tsp is equivalent to 5ml; 1 tbsp is equivalent to 15ml.

Use good-quality sea salt, freshly ground black pepper and fresh herbs for the best flavour.

Use large eggs unless otherwise suggested, ideally organic or free-range. If you are pregnant or in a vulnerable health group, avoid dishes using raw egg whites or lightly cooked eggs.

Individual ovens may vary in actual temperature by 10C from the setting, so it is important to know your oven. Use an oven thermometer to check its accuracy.

Timings are provided as guidelines, with a description of colour or texture where appropriate, but readers should rely on their own judgement as to when a dish is properly cooked.

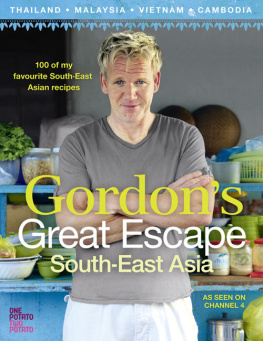

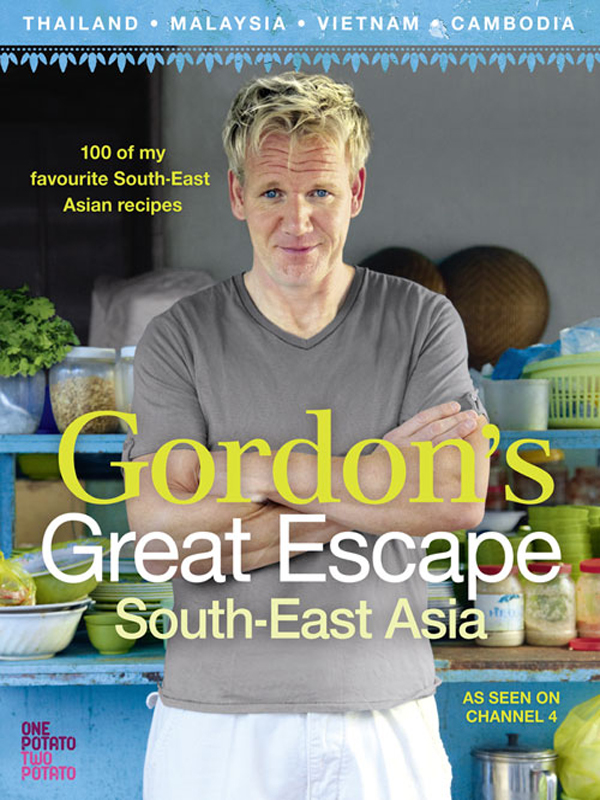

About 20 years ago, in my early days as a commis chef, I remember someone handing me this weird-looking stalk, which I soon learned was lemongrass. I was excited to discover an unfamiliar ingredient what did it taste like, where did it come from, were there more like this? That day taught me that as a chef you never stop learning, a lesson that holds true today. While I felt confident cooking French cuisine, I was yet to discover the ingredients, flavours and cooking techniques of places further afield. On my first Great Escape to India, I found that the best way to understand the food of another nation is to experience it in the country itself. For my second Great Escape my taste buds were in for an unforgettable rollercoaster ride as I set off on a pilgrimage to experience the culinary delights of not one country but four: Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam and Malaysia.

Thailand

Of the four countries on my itinerary, Thailand was the nation and cuisine I was most familiar with because I had visited it on a family holiday. I knew that at the forefront of Thai food is the creation of balance of sweet, sour, spicy, bitter and hot flavours, and that it has more to offer than the Thai green curries and Pad Thais that the West have adopted. It has long been said that some of the best food in Thailand can be found on the streets and I have to agree. There is no shortage of street sellers, whose wares vary from barbecued chicken ( Gai yang , Meat), green papaya salad ( Som tam, Salads), deep-fried shrimp (Coconut prawns, Snacks/appetisers), to drinks. A successful street stall can, indeed, be more popular than a restaurant.

As in any country, Thai dishes vary from region to region. In Southern Thailand the food is spicy (they love cooking with chillies and some dishes will blow you away), but in this region you will also find lots of salads (like the Kao Yum ) and, due to its close proximity to the sea, fish plays a major part in the diet. On my travels I ventured into a small village about one hour south of Ao Nang, where I spent the afternoon oyster fishing and was then taught some local dishes by a villager and expert called Ya. She spent hours creating the different curry pastes, but after all that effort I was relieved to see that each dish then took only moments to prepare such as the Khanom jeen (Curries) and Prawn and stink bean stir-fry (Stir-fries).

My journey then took me from the south to the north, as I travelled to Chiang Mai, one of the largest and most cultural cities in Thailand. It was there that I discovered the culture of Buddhist monks; in Thailand, Buddhism is the majority religion and you will often see monks going about their daily duties in their bright orange robes. Every day at around 6am the monks take to the streets, barefooted and carrying urns in which they collect food offerings from locals. Entering orders means you have to erase any ego and give up your worldly possessions, including money, so you rely on handouts to survive. One morning I removed my shoes and walked the pavements with the monks as their assistant; we were given mangoes, sticky rice, dried goods, meat, nuts and so much more. I am the first to admit that I am not a religious person, but I did find the generosity of the community astounding.

It is inevitable that with Buddhism playing such a large role in the lives of the Thai people, food has become interwoven with the religion. One of my favourite dishes that I discovered in Thailand was one I helped cook for a Buddhist house blessing; it was the Gaeng hung lay curry (Curries) which is traditionally served to monks at such ceremonies.

Cambodia

Often just viewed as the country in between Thailand and Vietnam, for me Cambodia is the forgotten kingdom. As a country that has gone through so much hardship suffering genocide during the reign of the Khmer Rouge, occupation by the Vietnamese and subjected to military coups Cambodia is finally on a slow path to recovery.

There is a charm about Cambodia; it feels to me how perhaps Thailand would have been over 15 years ago, before the arrival of mass tourism and consumerism. Arriving by plane, flying over field after field, the vastness of this country quickly became apparent. It is estimated that around 2 million people died during the genocide of the Khmer Rouge, while many others are thought to have died from starvation, and so many of the brave people I met on my travels round this country had stories to tell of those painful years. As the Khmer Rouge attempted to rewrite Cambodian history to begin it again from the start of their rule they destroyed all the literature and documentation they could find, including traditional family recipes and most food publications and cookbooks. As a result the country has had to develop a cuisine and a culture all over again since the collapse of the regime. I found it strange to be in a country that, in the twenty-first century, is still trying to establish its cuisine.

The biggest difference in Cambodian attitudes to food compared to the other countries I visited during this Great Escape, is that for many food is just sustenance. The ingredients used in Cambodian cooking are similar to those of Thailand and Vietnam, but the food is less spicy and more rustic. Cambodians have learnt how to make use of sources of flavour and protein that other countries avoid from insects to unusual herbs, flowers and fruits. As a chef I have sampled many different foods, but in Cambodia I chewed my way through tarantulas, duck-egg foetus, crocodile, frogs and various insects. Travelling between the cities and villages, there is a big divide between the peasant food of the countryside, which lacks fresh spices and meat, to the upmarket city food that uses an array of ingredients, including imported goods.

My Cambodian journey began in the northern city of Siem Reap, famous for the Angkor Wat, built in the twelfth century but still the worlds largest religious building. It was here that I learnt to cook traditional Cambodian dishes such as Fish amok (Fish). In the southern city of Phnom Penh I met an inspirational Cambodian chef called Luu Meng; he is paving the way for Cambodian cuisine as part of a new generation of innovative, creative chefs who are making it their mission to rediscover ancient Khmer cuisine. To find new inspiration, Luu regularly takes trips to the villages to seek out traditional recipes and also to see how people are cooking now. Taking my cue from Luu Meng, I travelled off to the jungle to be a guest at a tribal wedding, and this was the inspiration for the Khmer wild honey-glazed roast chicken (Meat) and Chocolate-covered toasted rice sticky squares (Desserts/drinks).