Copyright 1997 by Brian Moynahan

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

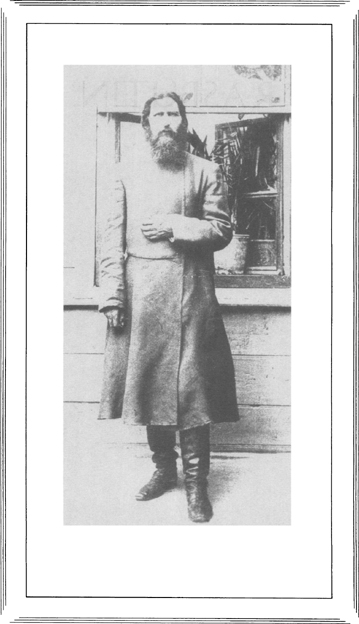

All photographs courtesy of the David King Collection, except the photograph of the Tsarevich Alexis and the sailor Nagorny, courtesy of the Endeavour Group U.K.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Moynahan, Brian.

Rasputin : the saint who sinned / Brian Moynahan.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN: 978-0-307-82646-6

1. Rasputin, Grigori Efimovich, ca. 18701916.

2. RussiaCourt and courtiersBiography.

3. RussiaHistoryNicholas II, 18941917. I. Title.

DK254.R3M69 1997 947.083092dc21

[B] 97-5025

Random House website address: http://www.randomhouse.com/

v3.1

Preface

Grigory Rasputin, holy man and intimate of the Russian royal family, was murdered in the basement of a St. Petersburg palace in 1916. To his many enemies he was the incarnation of evil genius; he died because they held him to be the real power behind a throne that his malign influence was destroying. Within a few weeks the three-hundred-year-old dynasty was swept away and a way of life perished with it.

Rasputin remains. He is the great survivor from the drowned world of the Romanovs. To some, he was once a saint; he is more often thought of now as the mad monk. He was not mad, or monk, or saint. He is a complex figure, intelligent, ambitious, idle, generous to a fault, spiritual, andutterlyamoral.

In his prime, when the censors forbade any public mention of him, newspaper editors were happy to trade heavy fines for the guaranteed increase in circulation Rasputin brought. After his death the memoirs of those who knew himleading politicians, a defrocked priest, secret police officers, women admirersbecame a mini-industry. His murderer, Prince Yusupov, was able to restore some of the fortune seized from him by the Bolsheviks with best-selling accounts of the killing and a slander suit against the Hollywood producers of a Rasputin movie. Eighty years on, Rasputin still inspires books, movies, and rock songs. The basement where he died is a tourist attraction.

Why? His life was remarkable in itself. He was peasant, prophet, and party-goer, a combination that is not common. He had apparent psychic powers, attested to but lacking medical explanation. He was, too, for all the medieval trappings that surrounded him, curiously modern. His skills as a spiritual leader and manipulator of souls match those of the latter-day guru; keep the sex, change drugs to drink and rock n roll to wild Gypsy music, and in his blend of charisma and outrage he is the precursor of the modern superstar. Ra-Ra-Rasputin

But it is in the ageless struggle between good and evil, so strong a motif in his existence, that his fascination truly lies.

Rasputin bewitches because his life is both romantic and repulsive. It can be seen as an actual fairy tale. Born in a Siberian cabin, he makes his way to the distant capital of a great empire and there wins the trust and affection of the tsar and empress. He has gifts of healing and saves the life of their hemophiliac son. Or he can be read as a study in wickedness; he is a hypnotist, who casts his spell over the innocent women he seduces and who leads Russia and its besotted rulers to revolution and ruin.

He is much more than an exhibit in an antique freak show (though it suited Russian Communists, with their belief in the impersonal forces of Marxism, to treat him as such). He was a legend in his lifetimeof few people is that old clich more aptand his legend did fatal damage to the reputation of the Romanovs and to the fabric of Russian autocracy. So did the reality that lay behind it; by the end seasoned diplomats and foreign correspondents had not the slightest doubt that, as his killers and the Russian public suspected, Rasputins influence was corrosive and immense. He is a historic personage.

It is the purpose of this book to show Rasputin, and the society on the edge of extinction in which he operated, in his true colors, not as a moral monochrome but rainbowed, as he was, and recognizably and fallibly human.

All dates are given here in the Julian calendar that was in use in Russia throughout Rasputins lifetime. It was twelve days behind the Western Gregorian calendar in the nineteenth century, and thirteen days behind in the twentieth. Thus, for example, the date of December 16, 1916, given for Rasputins death corresponds to December 29, 1916, in the Western calendar. This applies to events outside as well as within Russia. Rather than consistent transliteration from Cyrillic to the Roman alphabet, common usage is given for family names. First names are anglicized where, as with the tsar, for example, this is appropriate. Tsar and emperor, tsarina and empress are interchangeable; Nicholas is most commonly referred to as tsar, his personal preference, and Alexandra as empress, hers. I am indebted to Dr. Igor Bogdanov of St. Petersburg for his great help in skilled translation and painstaking research.

Contents

CHAPTER 1

Proshchaitye, Papa

I t snowed hard in Petrograd in the hours before the murder.

The fall of 1916 matched the war, bleak and endless, gray skies robbing the city of its energy in the brief hours of daylight. Foul winds drove down the quays by the Neva River, pungent with chemical fumes from munitions factories. Families from territories lost to the Germans huddled in sheds near the railroad stations. Their lamentations hovered in the air; they died of typhus and simple exhaustion, blown away like gossamer. Two in three streetlamps were unlit. The sidewalks were no longer swept. They filled with rubbish and slush and, from four each morning, with long lines of ill-clad men and garrulous women, waiting for bread.

The citys buildings, in faultless lines of pink granite and yellow- and green-washed stucco, had risen from bogs and marshes on piles driven by gangs of forced laborers two centuries before. When onshore winds raised the level of the Neva, alarm bells warned people to flee to higher stories before the floods poured into basement rooms. Now the city was drowning in its own ill humor.

Rasputin, Rasputin, Rasputin; one name pounded like surf on a crumbling shore, in the food lines, salons, rooming housesuniversally. It was like a refrain, a Petrograd lady wrote. It became a dusk enveloping all our world, eclipsing the sun. How could so pitiful a wretch throw so vast a shadow? It was inexplicable, maddening, almost incredible.

Grigory Rasputin was a muzhik, a dark peasant from a distant Siberian bog, a creature who had shat in the open like an animal when he was a boy, who still sucked soup from the bowl and ate fish with his fingers, whose body gave off a powerful and acrid odor, who could scarcely scrawl his name, but (what a but!) who it was rumored had the earenjoyed the bodyof the empress; who, with her, appointed the mightiest officials of state; who treated fawning duchesses, countesses, famous actresses, and high-ranking persons worse than servants and maids; who was plotting a separate peace with Germany; who could see the future. Inexplicable, indeed! Incredible, except that he was visible, a shaggy figure with a sable coat thrown over peasant boots and blouse, seen about town, catching cabs, dining at Donons, reeling out of the Gypsy houses in Novaya Derevnya blind drunk in the early hours. His very eyes betrayed his identity to strangers. The ballerina Tamara Karsavina, the most beautiful dancer of her generation, who had not seen him before, recognized him instantly in the street through their strange lightness, inconceivable in a peasant face, the eyes of a maniac.