Australia

HarperCollins Publishers (Australia) Pty. Ltd.

Level 13, 201 Elizabeth Street

Sydney, NSW 2000, Australia

http://www.harpercollins.com.au

Canada

HarperCollins Canada

2 Bloor Street East 20th Floor

Toronto, ON, M4W, 1A8, Canada

http://www.harpercollins.ca

New Zealand

HarperCollins Publishers (New Zealand) Limited

P.O. Box 1

Auckland, New Zealand

http://www.harpercollins.co.nz

United Kingdom

HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London, SE1 9GF

http://www.harpercollins.co.uk

United States

HarperCollins Publishers Inc.

195 Broadway

New York, NY 10007

http://www.harpercollins.com

Adam Nicolson is the author of many critically acclaimed and bestselling books on history and the landscape including Sissinghurst, Sea Room and When God Spoke English. The Mighty Dead was longlisted for the Samuel Johnson Prize, and he has won the Somerset Maugham Prize, the WH Heinemann Prize and the Ondaatje Prize. He has written and presented many series for television, most recently The Century That Wrote Itself, about life and writing in the 17th century. He is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and lives in Sussex with his wife and family.

The following images are reproduced with many thanks:

| Section I page 2 top | Jeremy Newick |

| Section I page 2 bottom | Andrew Palmer |

| Section I page 5 bottom | Jonathan Buckley |

| Section I page 8 top | Alexandre Bailhache |

| Section II page 2 top | Jonathan Buckley |

| Section II page 3 bottom | Alun Price |

| Section II pages 4-5 | Jonathan Buckley |

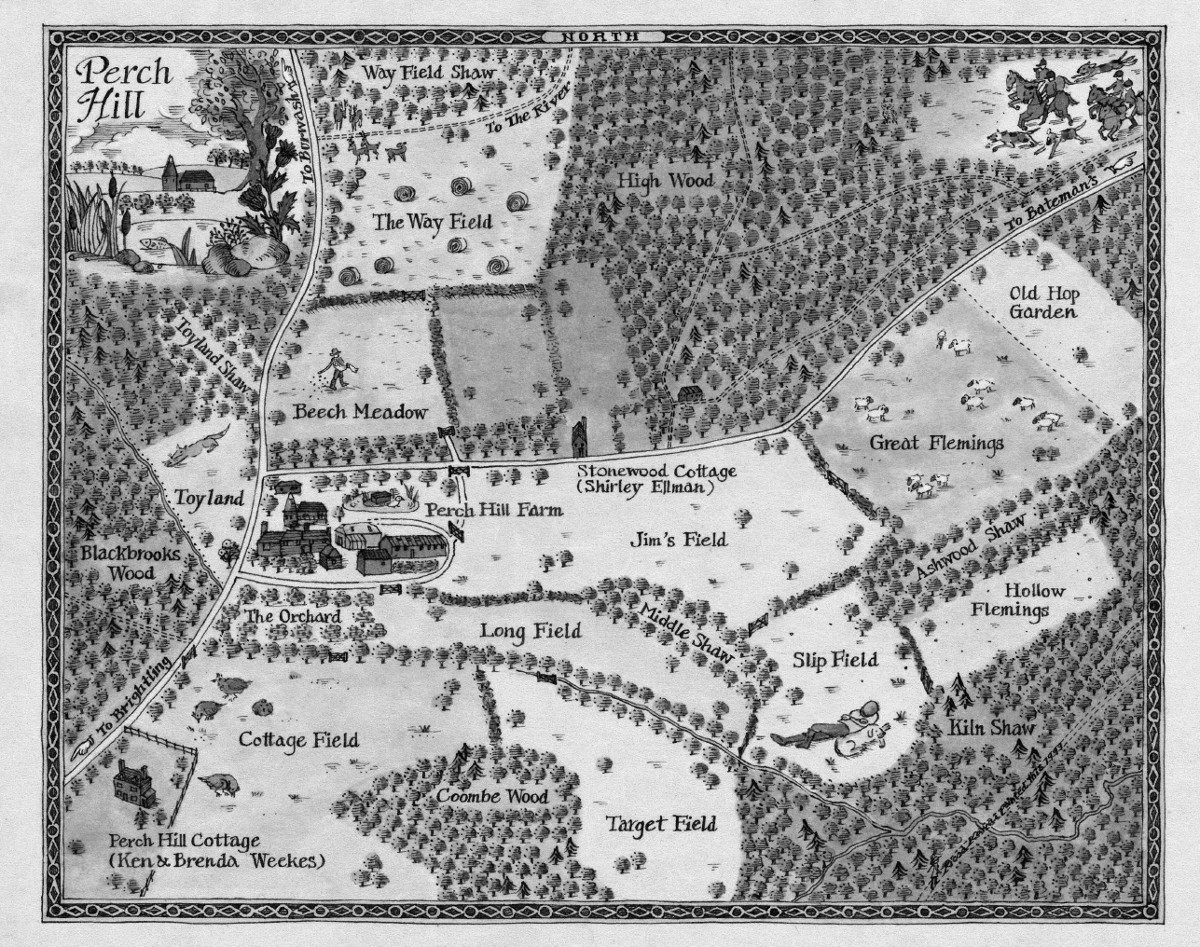

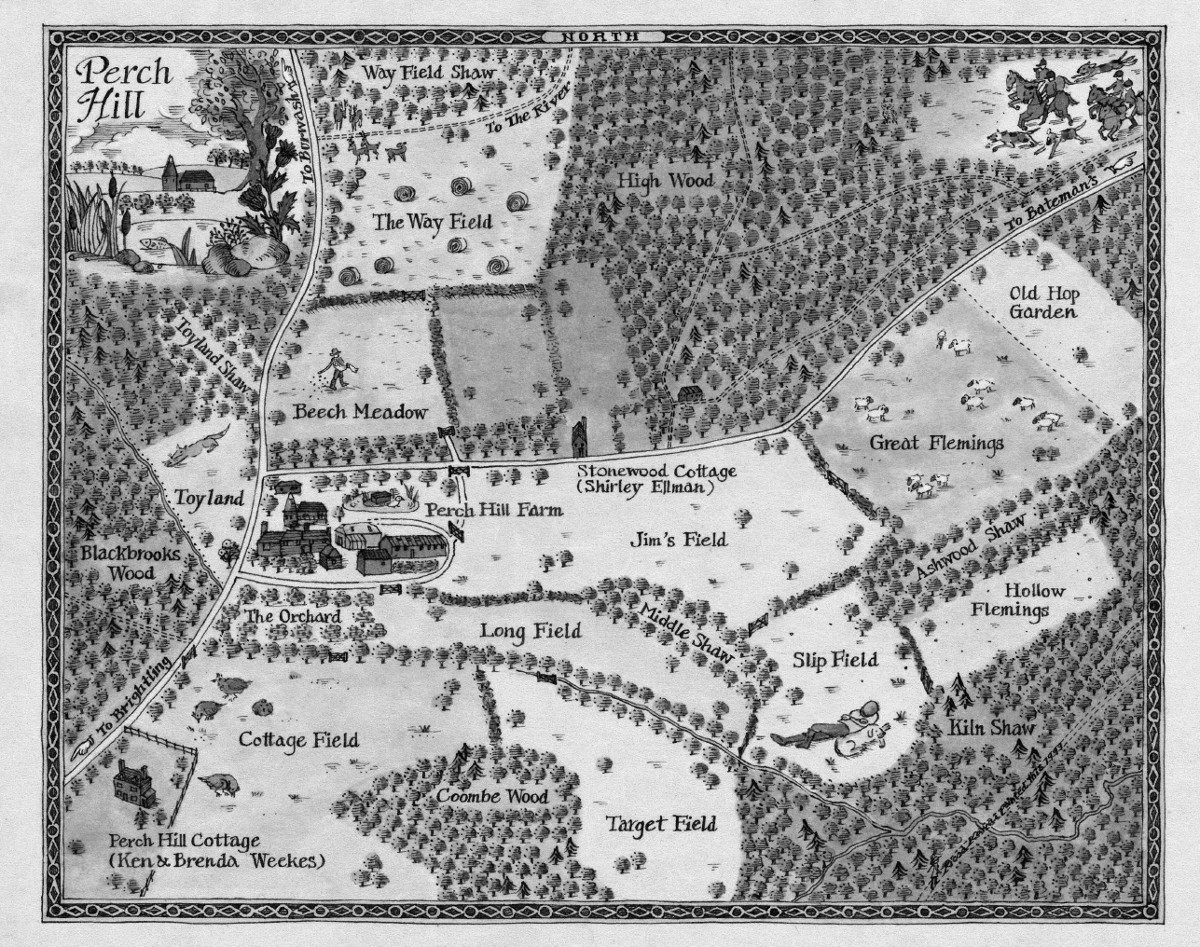

| Endpapers | Ricca Kawai. |

Large parts of this book first appeared in the Sunday Telegraph Magazine between 1995 and 2000 and two-thirds of it between hard covers in Perch Hill: a new life, published by Constable Robinson in 1999. I would very much like to thank Charles Moore, Alexander Chancellor, Aurea Carpenter and Nick Robinson, my various editors in those places, for all their help and guidance. This book takes the Perch Hill story on another full decade and looks again, with a slightly longer perspective, at those early days on the farm. This time I would again like to thank my editor Susan Watt, who has stood by me through thick and thin over many years, and my dearly valued agent Georgina Capel.

Nothing at Perch Hill could ever have happened without the people who work there and I would like to acknowledge with enormous and deeply felt thanks the difference which Tessa Bishop, Colin Pilbeam, Bea Burke, Angie Wilkins and Ben Cole have all made to our lives. Nothing, in my experience, can match the feeling which a joint and shared attachment to a place can give.

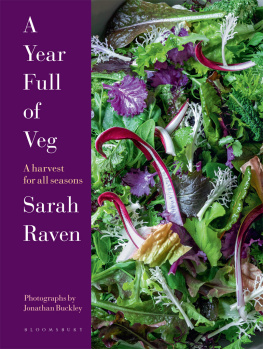

Almost needless to say as anyone who reads these pages will discover it soon enough for themselves the part of Sarah Raven in this story is not far short of the role played by gravity in the universe.

Adam Nicolson

Wetland: Life in the Somerset Levels

Restoration: The Rebuilding of Windsor Castle

Sea Room: An Island Life

When God Spoke English: The Making of the King James Bible

Atlantic Britain

Men of Honour: Trafalgar and the Making of the English Hero

Sissinghurst: An Unfinished History

Arcadia: The Dream of Perfection in Renaissance England

The Gentry: Stories of the English

The Mighty Dead: Why Homer Matters

Part One

BREAKING

Part Two

MENDING

Part Three

SETTLING

Part Four

GROWING

I F I think of the time when we decided to come here in 1992, it is a backward glance into the dark.

A summer night. I am walking home from Mayfair, from dinner with a man I fear and distrust. He is my stepfather and I burp his food into the night air. It is sole and gooseberry mousse. His dining-room is lined in Chinese silk on which parakeets and birds of paradise were painted in Macao some years ago. The birds have kept their colours, they are the colour of flames, but the branches on which they once sat have faded back into the grey silk of the sky. On the table are silver swans, whose wings open to reveal the salt. The Madeiran linen, the polished mahogany, the dumb waiter: its alien country.

My stepfather and I do not communicate. Its only worth reading one book a year, he says. The trouble with this country is the over-education of the young. Calling a parcels service Red Star is a sign of the depth of communist influence, even now, in England.

Nothing is given. I leave the house to walk across London to somewhere on the edges of Hammersmith, where I am living with Sarah Raven, the woman for whom, a few months previously, I have left my wife. That is a phrase which leaves me raw. Sarah has gone somewhere else this evening, to have dinner with friends, and wont be back until midnight or later. I have left as early as I can from the Mayfair house and think Why not? A warm night. A walk through London and its glitter in the dark, to expunge that padded house and all its upholstered hostilities.

There are whores in the street outside, bending down like mannequins to the windows of the slowing cars. Some of the women are so tall and so sweetly spoken they can only be men, with long, stockinged calves and a slow flitter to their eyes. One fixes me straight. Looking for company? she asks. Thank you, not tonight, thanks, and we move on.

I walk down Park Lane, where the cars are thick and the night heavy. The lights from the cars blip, blip, blip through the dark. Life is hurried. I pass the Dorchester and the Hilton, down to the corner where the subway drops into ungraffitied neon. Down and up and down again to the upper parts of Knightsbridge. Along there the windows gleam. A friend of mine has opened a shop in Beauchamp Place. It is lacquered scarlet inside and beautiful, with black Japanese furniture standing on the hard-wood floor.

On and out, increasingly out, away from the polish of the glimmer-zone, made shinier at night, to the open-late businesses of South Ken, where Frascati and champagne stand cooled in ranks behind glass and the Indian at the till leaves a cigarette always smoking on the ledge beside him. On, out, westwards, where occasional restaurants are all that interrupt the domestic streets now tailing into dark. The pubs have shut. It is nearing midnight.

For a stretch the street lights are broken, perhaps two in a row, and it is darker here. I think nothing of it. My mind is on other things. On what? I was thinking of a place where I have been happy, some kind of mind-cinema of it flicking through my brain: sitting back on the oars in the sunshine in a small boat off the coast of some islands in the Hebrides, where black cliffs drop into a sea the colour of green ink and the sea caves at their feet drive 50 yards or more into pink, coralline depths.

That night I was thinking of these things, of hauling crabs from the sea, scrambling among the hissing shags and peering down the dark slum tunnels where the puffins live, lying down in the long grass while the ravens honked and flicked above me and the buzzards cruised. My mind was away there that night.