Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

C ONTENTS

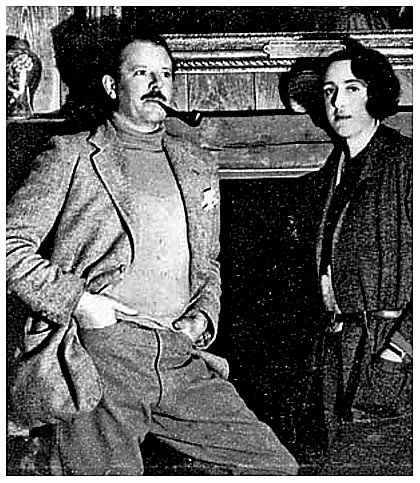

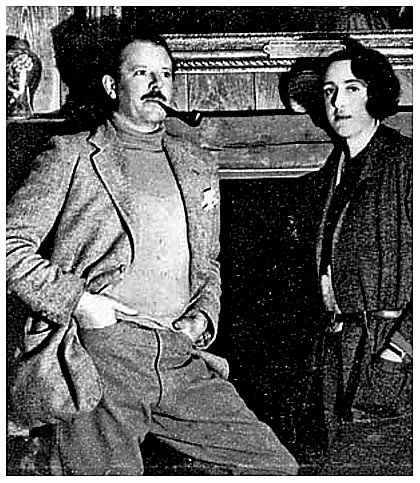

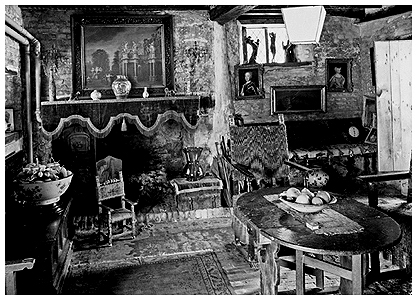

Harold and Vita standing in front of the fireplace in the newly restored South Cottage in the early 1930s.

I NTRODUCTION

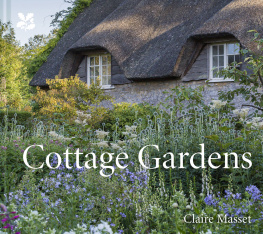

Gardens do not normally survive their creators, but Sissinghurst remains one of the most heart-rendingly beautiful spectacles in England. Its a garden in a romantic place, a ruined Elizabethan hunting palace flanked on two sides by a moat, in the pretty wooded part of the Kentish Weald. Enveloped in its own orchards and cornfields, its full of intimacies and, in summer, what its creator called the dark blue and gold of long views to distant hills. The combination of the buildings, the walls, and the planting around and within them has an extraordinary effect. There is very little else like it in the world for abundance and fullness: its fountains of roses, voluptuous, delicious-smelling, out-of-control geysers of flowers; the Purple Border, the White Garden, the Cottage Garden, all set within the terracotta brick frame. It is one of the twentieth centurys greatest creations, made eighty years ago in the course of about a decade by the writer Vita Sackville-West and her husband, the diplomat-cum-politician and writer, Harold Nicolson.

I remember my first sight of Sissinghurst when, just under thirty years ago, I was invited to a party on a Bank Holiday Monday, when the garden used to be closed. I was living in west London and, unusually for someone in their mid-twenties, I was already keen on gardening. I was training to be a doctor in the white-coat sterility of the Charing Cross Hospital wards, but I came from a plant-loving family and to keep me sane, Id started to grow things in my own back garden.

The party was held on a lovely sunny day in May, and I was excited to see this famous garden. I had not expected the beauty of the buildings. People had talked about the garden, but not the place, which as you approach from the narrow lane feels more French than English, more like a small village than someones home. And it all felt endearingly crooked, built from small, ancient bricks, and with an air of slight crumbliness at every corner.

I could hear the whole party out on the top lawn. I went in slowly, noticing the bronze urns at the front, full of a blue-grey pansy with large, flat, cheery flowers, ones I associated more with a Hyde Park bedding scheme than with these grand, sombre pots at the entrance to Sissinghurst. Their colour almost matched that of a large clutch of rosemary bushes with particularly dark blue flowers (Sissinghursts own hybrid, see ) to their right and left, and the hanging bells of a small straggly vine of Clematis alpina, breaking the line of the arch overhead. This was the beginning of my exposure to Sissinghursts painterly combinations that blue, a genius contrast to the colour of the Elizabethan and Tudor bricks, is for ever seared into my mind.

The garden was by then in the early 1980s owned by the National Trust. Nigel, Vita and Harolds son, had given it to the Trust in 1967 in lieu of his mothers death duties, so that he could be sure their creation would be preserved in perpetuity. Pam Schwerdt and Sybille Kreutzberger had been the head gardeners from a couple of years before Vitas death in 1962 and theyd been taking care of and raising the horticultural level of the garden for the twenty-five-odd years since.

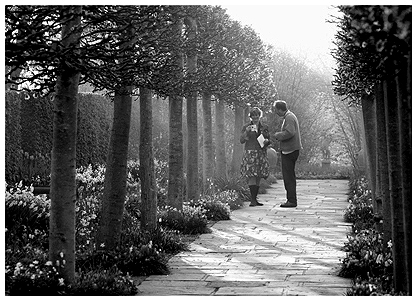

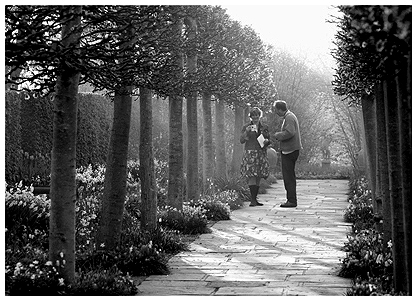

Adam and me, early on an April morning in the Spring Garden.

And now Ive had the joy of living in this wonderful place. A few years after first seeing the garden I married Adam, grandson of Vita and Harold, and when his father Nigel became ill and died in 2004, we moved to Sissinghurst. No longer a doctor and now with two children, I had become a gardener, and as someone passionately interested in the beauty of whats around me, Im lucky to have spent ten years of my life entwined with Vita and Sissinghurst. Her interiors, the rooms she made, are as rich, as stimulating and excitingly put together as her garden. In the morning I wake up in a bed brought by her from Knole, her nearby family home; I am surrounded by Chinese turquoise ceramic animals that belonged to Vitas mother. The light coming in from all three windows in our room radiates through amber flasks on the window ledges, which in Vitas childhood had stood in a window at Knole. There is the scent, on a spring morning, of the huge osmanthus trained on the wall below the windows one of Vitas favourite plants (see ), and as this fades its replaced by the spicy fragrance of wisteria and the sweet smell of the rose Blossomtime, a variety loved by Vita for its good mildew resistance, frothy pink flowers and long season, with buds still covering it right into autumn.

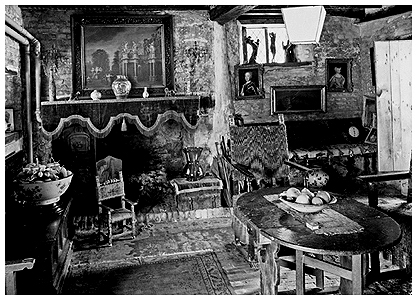

I plunged into her books and the more I learnt about Vita, the more excited I felt. I loved her taste, her habit of covering tables with Persian carpets as well as having them on the floor, her lustrous deep-green china egg hanging in front of our huge open fire to avert the evil eye, the turquoise Chinese lamps, the Duncan Grant painted box next to the Roman alabaster funeral urn in the middle of the chunky oak table, almost black with age. And all this before Id walked out into the garden, with its powerful colours and textures rich as a fig broken open, soft as a ripened peach, flecked as an apricot, coral as a pomegranate, bloomy as a bunch of grapes, as she described her favourite varieties of old-fashioned rose.

A typical Vita interior the Brew House, which she used as her workroom during the war. Its filled with many of her favourite things: a tapestry chair, a bronze hand on the high window ledge and a huge bowl of carved wooden fruit from a Mexican market.

My husband Adam became increasingly fired up by the idea of trying to enrich the whole Sissinghurst landscape. As he started to explore its history and all the related documents for the book he published in 2008, Sissinghurst: An Unfinished History, so our lives steadily filled with all the stories of what Sissinghurst had been in the past and during his own childhood. As time went on, I too increasingly revelled in Vitas writing and in the black and white photographs we have of Sissinghurst in Vita and Harolds day. Vitas words and those photographs show an exuberant place a garden brimming and overflowing. As Vita says of herself, My liking for gardens to be lavish is an inherent part of my garden philosophy. I like generosity wherever I find it, whether in gardens or elsewhere. I hate to see things scrimp and scrubby. Always exaggerate rather than stint, she says later, masses are more effective than mingies. Nothing was to be too tidy. Too severe a formality is almost as repellant as lack of any. This was to garden in the maximalist, not minimalist, way.