Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

C ONTENTS

To Sissinghurst

A few years ago, when I first had the idea of assembling a selection of Vita Sackville-Wests writings, some previously published and others not, her son Nigel Nicolson, with his customary generosity and elegance, gave me just the encouragement I needed. That encouragement has continued and I can only express my warmest gratitude. Without his gracious permissions, none of these unpublished writings would appear. My thanks to Michael Flamini and my editor Kristi Long at Palgrave, to the unfailing assistance of the librarians at the Lilly Library in Bloomington, Indiana, and at the Berg Collection at the New York Public Library, to my cousin Deborah Gage, and to my friends Carolyn Heilbrun, Rosemary Lloyd, Carolyn Gill, and Sarah Bird Wright, with whom I had the joy of writing Bloomsbury and France: Art and Friends (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), in which some of this material was first discussed.

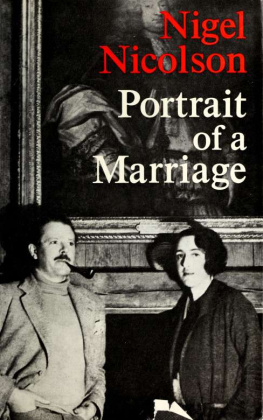

A good part of the information here comes from the superb biography by Victoria Glendinning: Vita: The Life of V. Sackville-West (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson; 1983). Other invaluable works include Nigel Nicolsons Long Life (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1987); Suzanne Raitts Vita and Virginia: The Work and Friendship of V. Sackville-West and Virginia Woolf (London: Clarendon Press, 1993); Louise DeSalvo and Mitchell A. Leaskas edition of The Letters of Vita Sackville-West to Virginia Woolf (London: Virago Press, 1992); and Robert Cross and Ann Ravenscroft-Hulmes Vita Sackville-West: A Bibliography (Winchester: St. Pauls Bibliographies; New Castle, Delaware: Oak Knoll Press, 1999).

This work was supported by a faculty research award from the City University of New York, and a visiting fellowship at the Lilly Library at Indiana University.

This is an anthology, but an unusual one, because it is selected from the writings of one person only, my mother, Vita Sackville-West. Most of her books have long been out of print, and some of her early poems and novels have become so rare, even in secondhand copies, that she ceased to mention them in her entry in Whos Who, but her name is still familiar as the author of The Edwardians, All Passion Spent, and The Land, as the creator of the famous garden at Sissinghurst, and as the subject of Victoria Glendinnings remarkable biography. Here Mary Ann Caws has contrived a highly original method of reintroducing Vita to a new generation, not only as a prolific author but as a woman whose experiences and ideas are still influential today.

Vita lends herself particularly well to this treatment since her range was so wide and her life so extraordinary. She was a poet, novelist, travel writer, biographer, journalist, and historian. She kept a diary, but only intermittently, and wrote innumerable letters, never leaving one unanswered whether it be a love letter from Virginia Woolf or an enquiryand she received dozens every weekfrom a reader of her garden articles.

She wrote with equal ease an intimate letter or a key passage in her latest book. Her manuscripts, apart from her poems, for which she wrote many drafts, reveal a fluency that was lacking in her conversation, for she remained shy and hesitant in company. I have at Sissinghurst a dozen unpublished plays and novels that she wrote at Knole during her childhood, and page after page is as free from correction as one of Anthony Trollopes manuscripts. Some of them are in French, others in Italian, for she had a great gift for languages, and all are suffused with a romanticism that never entirely left her.

Not many of her books are autobiographical. She wrote only one memoir, recording a torrid episode in her youth when she eloped to France with another woman, Violet Trefusis, which I published after her death in Portrait of a Marriage. From time to time she recorded in diary form specific journeys, like her holiday in France with Virginia Woolf in 1928 and her lecture tour of North America in 1933, and her two travel books, Passenger to Teheran and Twelve Days, are accounts of personal experiences. Characters like Lady Slane in All Passion Spent and Sebastian in The Edwardians are vaguely reminiscent of my grandmother and brother, and Vita herself figures marginally in the final pages of Pepita and in the history of her family, Knole and the Sackvilles. But about her personal life she was reticent, never writing for publication about lesbian love or the happiness of her marriage. It is therefore an added bonus that Mary Ann Caws has included in this volume examples of her letters and diary. In total it forms the autobiography she never wrote.

Vita, for all her mixed ancestryher maternal grandmother was a Spanish dancerwas English to the core. Intensely patriotic, romantically attached to the countryside both wild and tamed, and to the traditions of England as reflected in its literature and ancient buildings, she was nonetheless emotionally aroused by other cultures, particularly those of France, Italy, Greece, and Persia. Her only journey to the United States was less of a success because it was conducted in the least attractive circumstancesin midwinter, at the depth of a financial crisis, and in pursuance of an exhausting lecture tour that obliged her to hurry by train from city to city, constantly meeting people whom she would never see again and enduring a degree of entertainment and adulation which she felt wholly undeserved. But turning the troubled pages of her diary, one comes across sudden gleams of delight in an unusual person or a place like Niagara Falls or an Arizona ranch.

She was conservative, for instance, in her politics, but at the same time adventurous as a traveler, a writer, a gardener, and in her enduring regret that she was not born a boy who could have inherited Knole and who could have done the things that girls were not allowed or expected to do. But for all that she was a woman too, showing great tenderness toward people who were lonely or in trouble, and as a mother she revealed an understanding of schoolboy traumas well beyond her own experience.

So here you have a portrait of a remarkable person. It not only salvages an important part of her published workfrom which I would specially commend her short story Seducers in Ecuador and her long poem The Gardenbut reveals the private person behind the very public one, a woman of passion and determination beneath her outward gentleness and calm.

Vita Sackville-West, an aristocrat from a long and distinguished British lineage, delighted in the colorful mingling of Spanish and gypsy blood, with which she was endowed through the unusual circumstances of her maternal ancestors. She often portrayed herself as a hot-blooded irrational being, a fantasy played out in her acting the part of Julian or Mitya for her various loversin particular Violet Keppel Trefusis, who represents Eve to Vitas dark, romantic, masculine gypsy side.

Raised in privilege and speaking several languages, she was herself a surprising mixture, at once imperious and bashful, a public personality but essentially reclusive. Mostly schooled at home and with governesses, she was always conscious of not having had a lengthy formal education and this contributed to her shyness in the witty society of Bloomsbury, in relation to which she felt herself to be slow. Donkey West, as Virginia Woolf called her affectionately, was a friend of the group, and in particular of Virginia and Leonard Woolf, but not at its intellectual center as were the Woolfs.