Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West

LOVE LETTERS

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY

Alison Bechdel

CONTENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Vita Sackville-West (18921962) was born at Knole in Kent, the only child of aristocratic parents. In 1913 she married diplomat Harold Nicolson, with whom she had two sons and travelled extensively. They had an unconventional marriage, and throughout her life Sackville-West had a number of other relationships with both men and women. She wrote novels, non-fiction, and poetry, including The Land (1926), which won the Hawthorden Prize.

Virginia Woolf (18821941) was born in London. She became a central figure in The Bloomsbury Group, an informal collective of British writers, artists and thinkers. In 1912 Virginia married Leonard Woolf, a writer and social reformer. She wrote many works of literature which are now considered masterpieces, including Mrs Dalloway, To the Lighthouse, Orlando, and The Waves.

Alison Bechdel is the author of two internationally acclaimed graphic memoirs, Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic and Are You My Mother?: A Comic Drama. Fun Home was a New York Times bestseller, won an Eisner Award and was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. It was named a Best Book of the 21st Century by the Guardian, was adapted to a broadway musical which won five Tony Awards and is currently being adapted for cinema. For twenty-five years, she wrote and drew the comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For, a visual chronicle of modern life queer and otherwise considered one of the preeminent oeuvres in the comics genre. Alison Bechdel is guest editor of Best American Comics, 2011, and has drawn comics for Slate, McSweeneys, Entertainment Weekly, Granta, and The New York Times Book Review. In 2014 she was named as one of the recipients of the MacArthur Genius Award.

INTRODUCTION BY ALISON BECHDEL

When I was an undergraduate and just coming out as a lesbian, I slunk to a dimly lit, out-of-the-way place where I knew I would find other people like me the stacks of the library. Vita Sackville-West was not the first companion I encountered there, but she was certainly the most indelible one.

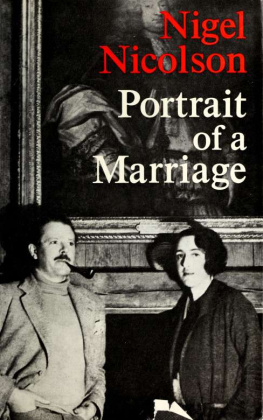

I found her in Portrait of a Marriage, her son Nigel Nicolsons 1973 book about his parents enduring and open relationship. I learned that both Vita and her husband, the diplomat Harold Nicolson, had numerous affairs, mostly with people of their own sex, while remaining otherwise devoted to one another, their children and their famous garden. The book also includes Vitas own account of her obsessive love affair with Violet Keppel in the early days of her marriage to Harold. I was spellbound by the image of Vita in Paris, passing as a man by wrapping her head with a khaki bandage not an unusual sight just at the end of World War I and strolling the streets with her lover. Who was this woman?

Towards the end of the book, the author provides a brief account of his mothers affair with Virginia Woolf. I hadnt yet read any of her books, but many of my friends had a postcard of her on their walls the ethereal Beresford portrait taken when she was twenty. Her fragile beauty fit the narrative of tragic and doomed feminist heroine that was cohering at this time: she was a genius; shed been molested by her step-brother; she struggled with some kind of mental illness; and in the end, after writing a few of the greatest books of the twentieth century, she had drowned herself. In some circles, more controversially, she was said to be a lesbian a bold claim in those days.

Lesbian or not, she was quite a character too. I was touched by the fact that as children, Nigel Nicolson and his brother instinctively liked Virginia. We knew that she would notice us, that there would come a moment when she would pay no attention to my mother (Vita, go away! Cant you see Im talking to Ben and Nigel) I learned a bit in Portrait of a Marriage about how Vita and Harold weathered Vitas relationship with Virginia, but I found myself longing for more of a window into what had gone on between these two redoubtable women. I wanted the details.

My wish was granted a few years later, when an edition of Vitas letters to Virginia was published. I had read some of Virginias books by then, so it was all the more rewarding to observe these two writers pushing and pulling their way to a profound intimacy the kind of intimacy I hoped to have with someone one day. Their passion for one another felt bound up for me with the new ground they were staking out for all women: Virginia in her work, and Vita in the world. I was in my twenties then, and despite how vividly this love story sprang from the page, it felt as if it had happened quite a long time ago, in the ancient past.

In middle age, I read the letters again. If I had had any doubt as to their continuing relevance, it would have been dispelled during one thorny patch of my own intimate life, when I found myself having passages quoted to me by two different women. This time though, the thing that impressed me most was how Vita and Virginia juggled all the elements of their fantastically busy lives public demands, creative work, family and social obligations, other relationships, including those with their husbands while still maintaining their own intimate connection.

Now at age sixty, a year older than Virginia was at her death, and ten years short of Vitas age when she died from cancer, I am struck by another aspect of the letters: the dogged fortitude of these women as they kept on going in the face of loss, illness, disillusionment and change. After a period of drifting apart, the two grow closer again as fascism spreads across Europe and the threat to their personal and intellectual freedom comes closer and closer to home. It has now been almost a century since Virginia and Vita fell in love, and strangely, that time feels much closer than it did when I was younger. Perhaps thats the perspective of age, perhaps its because the world seems once again to be approaching an inflection point. But its also a tribute to how intrepidly Vita and Virginia cast off the old forms and traditions of relationships to improvise something new.

The edition of the letters that I read in my youth consisted primarily of Vitas to Virginia, but included some extracts of Virginias to Vita. The collection you hold in your hands, while not a complete compendium of their correspondence, focuses on a more gratifying exchange of letters between the two. And even better, it includes diary entries from both women, as well as letters from Vita to Harold. These occasional shifts in point of view provide a fuller picture of the relationship, and add momentum to a narrative thats already as gripping as a well-plotted novel.

If the correspondence between Vita and Virginia were a novel, it would be criticised for the too-obvious names of its protagonists. One surging with life force as she strides halfway across the world and back, the other living primarily in the wild reaches of her own imagination. Virginias marriage to her husband Leonard was a chaste one, despite her brave attempt in the beginning at copulation. (Which, Vita relays to Harold, was a terrible failure, and was abandoned quite soon.) But Virginia and Leonard had their own kind of intimacy. He was her first reader, and nursed her through her collapses. They had no children, but their joint enterprise, the Hogarth Press, brought many important books into the world.

Next page