Copyright 2016 by Alan Hirsch

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

Cover design by Jarrod Taylor

Interior design by Tabitha Lahr

Counterpoint

2560 Ninth Street, Suite 318

Berkeley, CA 94710

www.counterpointpress.com

Distributed by Publishers Group West

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

e-book ISBN 978-1-61902-771-8

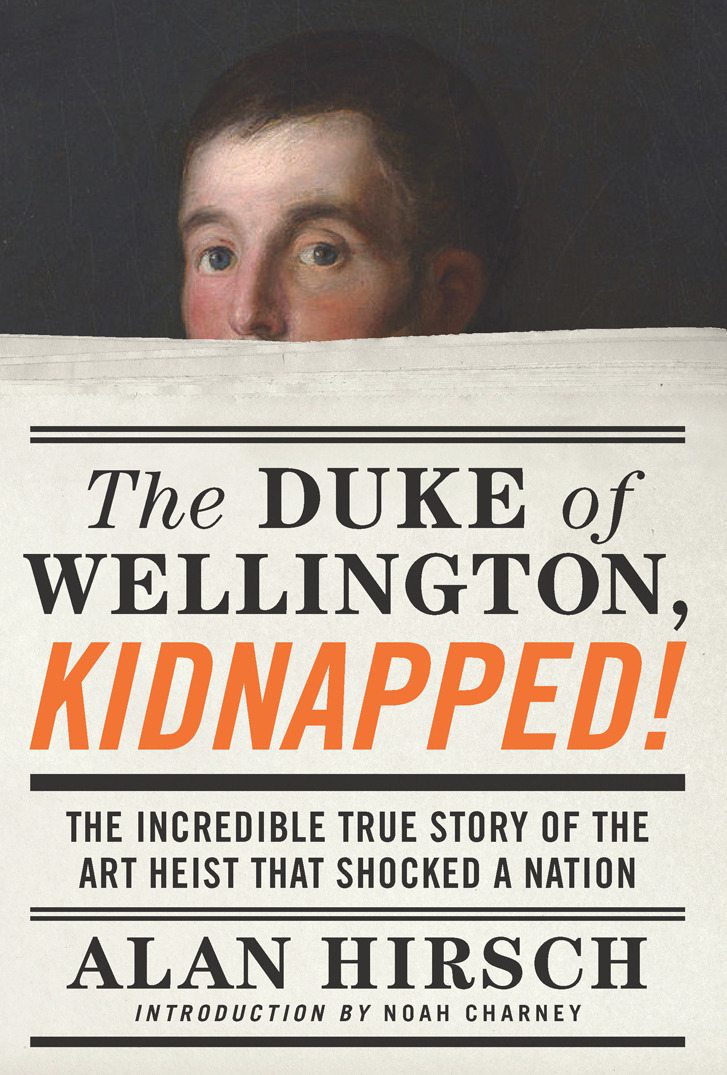

T he only successful theft from Londons National Gallery took place on August 21, 1961, when a brazen thief stole Goyas Portrait of the Duke of Wellington. One of the most bizarre incidents in the history of art theft, the Goya heist baffled police. Someone somehow sneaked into the National Gallery through an unlocked bathroom window, evaded security guards, and made off with a painting that had just been saved from sale to an American tycoon by the British government. The portrait of the English war hero had gone on display at the National Gallery on August 3less than three weeks later, it was gone.

The press had a field day, and the theft infected the popular imagination. In the background of the first James Bond movie, Dr. No, which was filmed soon after the crime, one can see a copy of the missing Goya portrait decorating Dr. Nos villainous hideout.

Just ten days after the theft, the London police received the first of many bizarre ransom notes. They promised the safe return of the painting in exchange for discounted television licenses for old age pensioners.

Surely this was a joke? But the ransomer identified marks visible only on the back of the painting, proving that it was in his possession. The ransomer, whose notes were theatrical and flamboyantly written, thought it outrageous that the British government would spend a large sum on a painting when retired British citizens had to pay to watch television. There seemed to be no personal motivation for the theft, only outrage at the governments TV license scheme.

But the police would not negotiate, and a merry dance ensued: part true crime, part farce, all fascinating and set against the backdrop of Swinging Sixties London. The story is irresistible, and perhaps the biggest surprise of all is that there has never been a book on the most famous art heist in British historyuntil now.

Alan Hirschs fine book tells the story of a cinematic, quirky, relatively harmless art crimethe sort that echoes popular film and fiction (it certainly sounds implausible) but that represents the exception in this type of crime rather than the rule. Thanks to media attention, we tend to think of art crime as a handful of big, bold, entertaining museum heists of famous artworks per year. In fact, tens of thousands of art crimes are reported every year the world over. (And many more go unreported.) Knowledgeable sources like SOCA (the UKs Serious Organized Crime Agency), Interpol, and the US Department of Justice have noted that art crime is among the highest-grossing criminal trades worldwide, up there with the drug and arms trades, and is a major funding source for organized crime and even terrorist groups, as recent headlines regarding ISIS have made painfully clear. It is certainly not just the art that is at stake.

While all the tea in China couldnt convince me to spend a day with armed fundamentalist terrorists, Id gladly take tea with Kempton Bunton, the portly retired cab driver at the center of Alan Hirschs book. He is the sort of character who would be more at home in a nineteenth-century comic novel than a real-life art heist. When I teach the history of art crime at the ARCA Postgraduate Program in Art Crime and Cultural Heritage Protection, which runs every summer in Italy and is the only interdisciplinary academic program in the world where one can study art crime, Bunton is inevitably the best-remembered of the scores of thieves, traffickers, forgers, tomb raiders, and, yes, terrorists my students encounter. While his bizarre story is an exception to the general rule of art crime as sinister and very serious indeed, it is a bright star among real stories that often eclipse their cinematic counterparts in panache, surrealism, and audacity. Everyone loves a quirky character, everyone loves a true crime story (especially if it has a cinematic courtroom scene at its heart), and everyone seems to love to hear about art theft. This book has it all. As long as the realities are kept in perspective, we can choose the charming true crime story over more gruesome, messier ones. And youll find no true story in the history of crime that is more charming, implausible, and Dickensian than this one, cleverly told by Hirsch. It is a must for anyone who likes to be entertained and diverted while also receiving a sound and important history lesson.

When Buntons case went to trial, the defense ingeniously invoked an odd loophole in British law. It had to convince a judge who, like Bunton, seemed to have tumbled out of the pages of a Dickens novel. The courtroom drama that ensued was sometimes hilarious, sometimes tense, and always riveting, but was the wrong man on trial? This book provides the definitive answer. It also explains how the case sparked a major change in UKs criminal law.

Another law eventually changed too. Television licenses were revoked for old age pensioners, satisfying, long after the fact, the unusual ransom demands of Kempton Bunton. Floating on his cloud up in heaven, Bunton must be looking down upon us with a satisfied smile. For not only was his motive for the theft (eventually) fulfilled, but for decades the police believed what he wanted them to: that he was, in fact, the thief.

Drawing from exclusive new archival material, including Buntons own unpublished memoirs, Alan Hirsch sets the record straight and, for the first time, tells the complete story of Londons most famous art theft and kookiest criminal.

Dr. Noah Charney

Ljubljana, Slovenia

February 2016

For more information on real art crime and how to study it, visit www.artcrimeresearch.org.

F or years I planned to write a book about the theft of Goyas Portrait of the Duke of Wellington because it had everything: an impossible crime and wacky investigation culminating in a bizarre confession and courtroom drama; a stranger-than-life culprit with a ludicrous motive; and an outcome so improbable that it inspired the United Kingdom to change its criminal code. All of that would have been more than enough, but something extra made the case irresistible: I doubted Kempton Buntons guilt. The only thing better than top-flight true crime is unsolved top-flight true crime.

While I planned to research the case thoroughly, I was under no illusion that I was likely to solve the case. After all, the theft had taken place a half century before, and most of the major players, including Kempton Bunton, were deceased. But I could pore over the trial transcripts and National Gallery records and talk to members of Buntons family (if they were willing) and the few survivors with some connection to this ever-receding event. Even without solving the crime, there was a great story to tell.