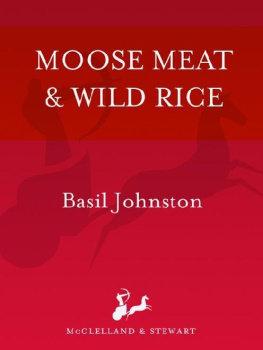

Copyright 1982 by McClelland & Stewart

Trade paperback edition published 1987

Emblem edition published 2008

Emblem is an imprint of McClelland & Stewart Ltd.

Emblem and colophon are registered trademarks of McClelland & Stewart Ltd.

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without the prior written consent of the publisher or, in case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency is an infringement of the copyright law.

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION

Johnston, Basil, 1929

Ojibway ceremonies

eISBN: 978-1-55199-591-5

1. Ojibway Indians Fiction.* 2. Indians of North America Fiction. I. Title.

PS 8569.048044 C 813.54 C 82-095242-7

PR 9199.3. J 65044

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program and that of the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Media Development Corporations Ontario Book Initiative. We further acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council for our publishing program.

McClelland & Stewart Ltd.

75 Sherbourne Street

Toronto, Ontario

M 5 A 2 P 9

www.mcclelland.com

v3.1

Contents

Preface

To understand the origin and the nature of life, existence, and death, the Ojibway speaking peoples conducted inquiries within the soul-spirit that was the very depth of their being. Through dream or vision quest they elicited revelation knowledge that they then commemorated and perpetuated in story and re-enacted in ritual. But in addition to insight, they also gained a reverence for the mystery of life which animated all things: human-kind, animal-kind, plant-kind, and the very earth itself.

In private, hunters and fishermen sought the patronage and the pardon of the manitous (mysteries) who presided over the animals and the birds; and medicine men and women invoked the mysteries to confer curative powers upon the herbs that were used in their preparations. In public, the people conducted rituals and ceremonies to foster upright living; petitioned Kitche Manitou and the deities for blessing; or offered thanksgiving for game and abundant harvest. From the origin and form of these ceremonies, and from the substance of the chants and prayers, the Ojibway speaking peoples understanding and interpretation of moral order can be discovered.

I dedicate this work to the memory of my father and mother, Rufus and Mary, both deceased. I also wish to acknowledge the guidance of my friend and teacher, Sam Zawamik, and the encouragement of my friend and colleague, Dr. E.S. Rogers of the Department of Ethnology of the Royal Ontario Museum. I wish, too, to express my appreciation to my own family and friends for their patience during the long, silent work.

List of Place Names

The Naming Ceremony

Wauweendaussowin

THE BEGINNING

Waubizeequae (Swan Woman) cradled her baby in the crook of her arm, and pressed it to her breast.

Ogauh! Would you ask Cheengwun to name our son? she asked her husband.

Ogauh (Pickerel) hesitated. Should we not wait until he is a little bigger, a little older? he said. He was not against the naming of their son, he simply felt no urgency for doing so. Among the Anishnabeg (or Ojibway) people, haste was unnecessary. Babies were often named much later, a year or sometimes two years after they were born. For people to be named after they were ten or even twelve was not unknown.

But Waubizeequae insisted. I will not wait until our baby is sick before we have him named. I wish to have him named soon.

Ogauh nodded and got to his feet. He crossed the village grounds which were vibrant with the laughter of children and vital with the stir of men and women in their tasks. Children either played tag or wrestled or carried bundles of twigs and branches for the fires. Near the centre of the village, an old woman sat on the ground bent over a hide that she was fashioning into a jacket. Further on, Auniquot (Cloud) was lashing ribs to the gunwale of a canoe; and beyond that, women were hanging strips of meat on horizontal poles or pressing berries in birch bark containers. Except for the running of the children, there was no attempt to hurry the pace of life. Even the sounds of the village, the barking of the ever-present dogs, the quiet talk of women, and the muffled laughter of old men, seemed relaxed.

Cheengwun (Meteor) was not at home. Kitchi-Zaudee (Great Poplar) thought that the old man had gone up the hill to gather medicine at the far end of the ridge. When Ogauh finally found Cheengwun he was on his knees in the middle of his work, and because gathering medicine was much more than an act of digging roots, he did not disturb the medicine man. Chopping leaves and pruning stalks and unearthing roots was in itself an enactment of ritual, the deepest expression of reverence for the mystery of life and the essence and curative power of the plant. During the collection, Cheengwun addressed the plants as sentient beings, petitioning them to confer their healing powers upon the sick, and asking their pardon for removing them from the land and from their hold upon life. The sick need you. You are strong and well and have done your work. Kitche Manitou has endowed you with an essence for your good and for the well-being of others. I have come for you, not for myself, but for the sick that they may get well. Pardon me for taking you. To you and Kitche Manitou I offer this tobacco. Thus Cheengwun spoke to each plant as he removed it from its place and implanted an offering of tobacco in the soil.

Cheengwun folded and tied his bundle before he got up. There must be something, he said, without looking up, as if he knew that Ogauh had been there all along.

Ogauh spoke. I have come to ask you to name our son.

Oh! Cheengwun aspirated an expression which by its tone was intended to give consent, before he swung the bundle over his right shoulder.

On the way back to the village Ogauh walked behind Cheengwun, who stopped several times to examine plants by feeling their texture, handling them lightly as one would touch a delicate and sensitive object. His mind and eye were focussed on nothing but the plants that grew in profusion on the forest floor. It was as if Ogauh was not there. Only the plants mattered.

But back in the village, just as they parted, Cheengwun said to Ogauh, I will let you know the time.

THE SEARCH

On the surface, giving a name was easy. But before the ceremony could take place there were days of meditation and nights of dreaming. For a name was not merely an appellation, or a term of address; it was an identity at the time it was bestowed, merging later into reputation. Until named, a child was without identity except to its mother and father. It was no more than a presence with a potential and, with care and good fortune, a future. That and nothing more. Hence the namers task was not a light matter. Not only did the namer have to give a name, but he had also, by virtue of being a namer, to assume certain responsibilities for the child. By being asked to name a child, the namer was asked to be like a second father.