I NTRODUCTION

The Missing Chapter

O N AN UNKNOWN DAY LATE IN THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY , an unidentified hand clumsily cut away part of the text from the most politically sensitive section of The Secret History of the Mongols. The censored portion recorded words spoken by Genghis Khan in the summer of 1206 at the moment he created the Mongol Empire and gave shape to the government that would dominate the world for the next 150 years. Through oversight or malice, the censor left a single short sentence of the mutilated text that hinted at what had been removed: Let us reward our female offspring.

In the preceding section of the text, Genghis Khan bestowed offices, titles, territories, and vassals upon his sons, brothers, and other men according to their ability and contribution to his rise to power. But at the moment where the text reported that he turned to the assembly to announce the achievements and rewards of his daughters, the unknown hand struck his words from the record. The censor, or possibly a scribe copying the newly altered text, wrote the same short final sentence twice. Perhaps the copyist was careless in repeating it, or perhaps the censor deliberately sought to emphasize what was missing or even to taunt future generations with the mystery of what had been slashed away.

More than a mere history, the document known as The Secret History of the Mongols recorded the words of Genghis Khan throughout his life as he founded the Mongol nation, gave his people their basic laws, organized the administration, and delegated powers. It served as the biography of a tribe and its leader as well as the national charter or constitution of the nation that grew into a world empire. Only the most important members of the royal family had access to the manuscript, and therefore it acquired its name.

The Secret History provides an up-close and personal view of the private life of a ruling family that is unlike any other dynastic narrative. The text records the details of conversations in bed between husband and wife; of routine family problems as well as arguments over who had sex with whom; and expressions of the deepest fears and desires of a family who could not have known that they would become important actors in world history. Many episodes and characterizations, particularly those regarding Genghis Khans early life, are unflattering. It was not written by sycophantic followers currying favor, but by an anonymous voice dedicated to preserving the true history of one of the worlds most remarkable men and the empire he founded. That did not mean that the history was available to just anyone, however.

The Mongols operated possibly the most secretive government in history. They preserved few records, and those were written in the Mongolian language, which their conquered subjects were not allowed to learn. While Mongol khans gave away jewels and treasures with little evidence of covetousness, they locked their documents inside the treasury and kept them closely guarded. As Persian chronicler Rashid al-Din wrote in the thirteenth century: From age to age, they have kept their true history in Mongolian expression and script, unorganized and disarranged, chapter by chapter, scattered in treasuries, hidden from the gaze of strangers and specialists, and no one was allowed access to learn of it. Both the secrecy of the records and the apparent chaos in which they were kept served the purposes of the rulers. With such an unorganized history, the person who controlled the treasury of documents could pick and choose among the papers and hide or release parts as served some political agenda of the moment. If a leader needed to discredit a rival or find an excuse to punish someone, there was always some piece of incriminating evidence that could be pulled from the treasury. Following the example of Genghis Khan, the early Mongol rulers clearly recognized that knowledge constituted their most potent weapon, and controlling the flow of information served as their organizing principle.

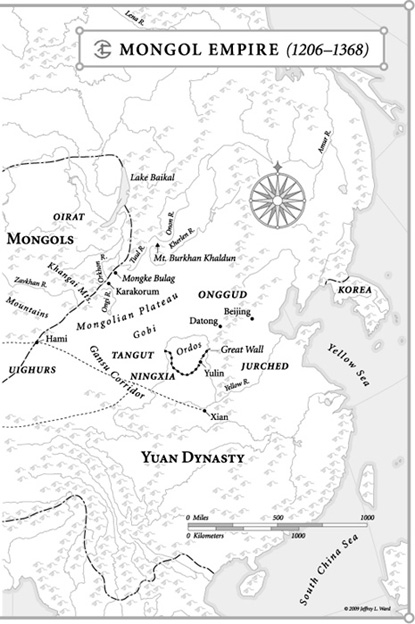

Genghis Khan sired four self-indulgent sons who proved good at drinking, mediocre in fighting, and poor at everything else; yet their names live on despite the damage they did to their fathers empire. Although Genghis Khan recognized the superior leadership abilities of his daughters and left them strategically important parts of his empire, today we cannot even be certain how many daughters he had. In their lifetime they could not be ignored, but when they left the scene, history closed the door behind them and let the dust of centuries cover their tracks. Those Mongol queens were too unusual, too difficult to understand or explain. It seemed more convenient just to erase them.

Around the world, the influential dynasties of history exhibit a certain uniformity in their quest for power, and they distinguish themselves from one another primarily through personal foibles, dietary preferences, sexual proclivities, spiritual callings, and other strange twists of character. But none followed a destiny quite like that of the female heirs of Genghis Khan. As in every dynasty, some rank as heroes, others as villains, and most as some combination of the two.

Rashid al-Din wrote that there are many stories about these daughters. Yet those stories disappeared. We may never find definitive accounts for all seven or eight of Genghis Khans daughters, but we can reassemble the stories of most of them. Through the generations, his female heirs sometimes ruled, and sometimes they contested the rule of their brothers and male cousins. Never before or since have women exercised so much power over so many people and ruled so much territory for as long as these women did.

References to Genghis Khans daughters have come down to us in a jumble of names and titles with a stupefying array of spellings, according to how each sounded to the Chinese, Persians, Armenians, Russians, Turks, or Italians who wrote their stories. Each source differs on the number of daughters. The