Copyright 2013 by David Oliver Relin.

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

R ANDOM H OUSE and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Relin, David Oliver, 19622012.

Second suns: two doctors and their amazing quest to restore sight and save lives / David Oliver Relin.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-679-60356-6

I. Title.

1. Tabin, Geoff. 2. Ruit, Sanduk. 3. Cataract ExtractionhistoryNepal. 4. Cataract ExtractionhistoryUnited States. 5. OphthalmologyNepalBiography. 6. OphthalmologyUnited StatesBiography. 7. Blindnessprevention & controlNepal. 8. Blindnessprevention & controlUnited States. 9. Developing CountriesNepal. 10. Developing CountriesUnited States. 11. History, 20th CenturyNepal. 12. History, 20th CenturyUnited States. WZ 100]

617.742059dc23 2012026082

www.atrandom.com

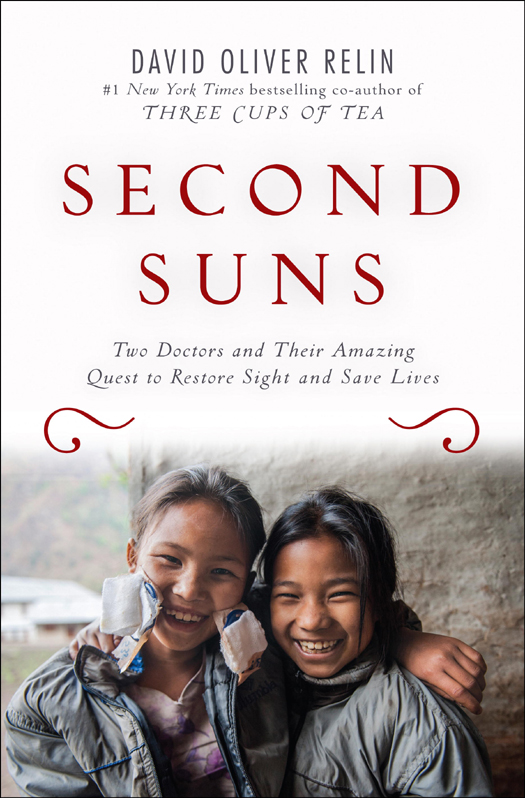

Jacket design: Gabrielle Bordwin

Jacket photographs: Stefano Levi (girls),

Alexander Yu. Zotov (mountains)

v3.1

Contents

See You

See YouThis world is blinded by darkness. Few can see.

Become a lamp unto yourself.

Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha, from the last teaching

There is the Nepal of myth, the ice-and-rock realm of Mount Everest, the roof of the world. Then there is the country where most Nepalese actually live. I was still unfamiliar with that other, more earthly, Nepal when I first came to the Khumbu.

I had hiked up to the village of Thame, at twelve thousand feet, with Apa Sherpa. He stood a wiry five foot three and weighed perhaps 120 pounds. Apas hair was cropped close, and his head was a thing of beautysmooth and sun-browned like an exotic nut. Looking at him, youd never guess he was one of the worlds greatest athletes. But by the age of fifty, Apa had climbed to the top of Everest twenty times; no one had ever stood on the sharp peak of the earths highest point more often.

Apa had invited me to Thame to meet his family and gather material about his career in the mountains, hoping that I would write a book about him. I was intrigued, not simply because of his high-altitude achievements but because, unlike many publicity-seeking Western mountaineers, Apa, like most Sherpas, climbed not for glory but to feed his family. He had also dedicated his most recent expeditions to raising money for the schools that surrounded the mountain his people know as Chomolungma, Goddess Mother of the World, and to raising awareness of the toll that global warming was taking on the Khumbus receding glaciers.

By the time I arrived, the five-room school Sir Edmund Hillary had built in Apas village was planning to lay off two of its teachers because of funding shortages, which would force the older students to walk six hours each day if they wanted to continue attending classes. And the lower portion of Thame had recently been washed away when a lake of glacial meltwater overran its rim and thundered through the valley where Apa had been raised. His familys home had been spared. So had the house next door, which belonged to the family of Tenzing Norgay, the first person to step onto the summit of Everest, alongside Hillary, in 1953.

Apa Sherpa had taken advantage of his prominence as a mountaineer to move his family from Nepal to suburban Salt Lake City, where his three children could count on a quality education. But his American dream hadnt panned out as hed expected; Apas attempt to create a line of outdoor clothing had crash-landed shortly after its launch. When he emailed me to introduce himself, he was working in a metal shop, stamping out road signs for Utahs highways. Apa wasnt bitter. He described his achievements on Everest with such matter-of-fact modesty that I agreed to accompany him to Nepal on his next expedition.

As the stone and ice immensities of the Himalaya thrust into view around every twist in the trail, Apa led me over swaying suspension bridges and up steep rock staircases with effortless grace. And as we traveled together, he proved to be one of the kindest people Id ever met. Whenever my breathing became ragged, hed put a hand on my shoulder. Slowly, slowly, hed say, guiding me to a seat on the nearest stone wall or to a bench at a tea house, where hed pretend that he, too, was anxious to rest.

At altitude, the air was beautifully crisp, the peaks fairy-tale white. The sky draped over the low stone homes of Thame was the unblemished blue of tourist brochures. Each morning Id wake to the gentle alarm of yak bells. Cocooned in my warm sleeping bag, Id open my eyes, peer through puffs of my breath, and watch wood smoke from breakfast fires drift across low stone walls that divided pastures from potato fields. On one side, shaggy black pack animals foraged for grass shoots with delicate lips. On the other, slender plants angled toward the sun, pale green with new growth.

I interviewed Apas elderly mother as she spun her prayer wheel and kept my tin mug of butter tea topped up. I also spoke with Apas climbing partners, brothers, aunts, uncles, and cousins. I was so enchanted by Thame that I lingered there for several days, resisting the conclusion that was becoming as clear to me as the air above the village: that writing a book about a man climbing the same mountain twenty times, even the worlds highest mountain, even for admirable reasons, was not something I could do well.

Apa was preparing for another attempt on Everest, and though I protested that I could find my way back down the trail to the airstrip at Lukla, where I planned to catch a small plane to Kathmandu, he insisted on accompanying me for the three-day trek. His middle-aged sister-in-law served as our porter, carrying, by a strap balanced across her broad forehead, the expedition bag I could barely lift. And with each step closer to the world of cities, with each foot of altitude lost, I felt more acutely how lucky I had been to get a glimpse into the life of this gentle man, and how much I regretted failing him.

Apa left me at Lukla. I promised that when he returned from Everest, wed hold a fund-raiser together for the Thame School, which we managed to do a few months later. And I delayed telling him about my pessimistic view of the books future. I didnt want him carrying that disappointment on his way back to the top of the world.

I spent a day sitting on a foggy airstrip, feeling like Id been cast out of a kind of paradise, waiting for a window to open in the weather so a Yeti Airlines propeller plane could land. Dreadlocked European trekkers lounged against their backpacks, smoking hash or playing hacky sack on the empty runway, killing the hours. Sheets of fog blew by like possibilities, blanketing all of us in gloom, or opening narrow boreholes that revealed the snowfields of the high peaks, hinting at and then denying the splendor that surrounded us. The runway tilted steeply downhill, and everything felt out of balance. Though I was looking up, whenever I got a glimpse of clear sky I felt I was staring down into the ice-blue depths of a glacier.

The sight of those mountains made me think of a promise Id made to another climber.