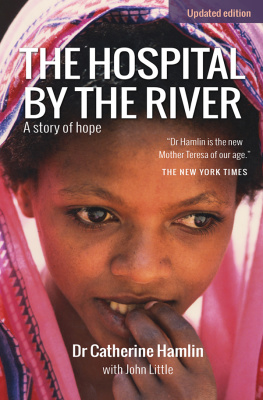

About Healing Lives

A story of friendship like no other... breathtaking in its tenderness and inspiration. The Hon. Dame Quentin Bryce AD CVO

Two incredible women, an unlikely friendship, and a united mission to save the lives of some of the worlds poorest and most desperate women.

Healing Lives reveals the untold tale of Mamitu Gashe, Dr Catherine Hamlins protge, and the inspiring almost 60-year friendship between the two women.

In 1962, three years after Drs Catherine and Reg Hamlin arrived in Ethiopia, an illiterate peasant girl sought their aid. Mamitu Gashe was close to death and horrifically injured during childbirth after an arranged marriage at the age of just fourteen to a man shed never met in a remote mountain village.

The Hamlins Addis Ababa Fistula Hospital saved her and, in return, Mamitu dedicated her life to Catherines mission. Under the iconic doctors guidance, Mamitu went from mopping floors and comforting her fellow patients, to becoming one of the most acclaimed fistula surgeons in the world, despite never having had a days schooling.

This is the moving story of the friendship that saved the lives of over 60,000 of the poorest women on earth.

CHAPTER 5

CHILD BRIDE

Mamitus life feels relatively carefree. She doesnt think much about the future, assuming everything will just trundle along the way it always has. Her sisters and friends talk occasionally about marriage, but that always seems a long way off. Its a mysterious realm governed by unwritten rules of culture and tradition, run by parents and their friends in accordance with age-old custom, and not much to do with her at all.

But in 1959, everything in Mamitus world comes crashing down.

She arrives back at the family tukul from fetching water with one of her sisters to find four elders from another village, all men, with her father. The girls are excited to see visitors, but Mamitus stepmother stops them from entering the tukul and shoos them away.

Go! she tells Mamitu. Go and hide. Dont let them see you!

Mamitus confused but does as shes told. She runs off into the fields, dragging her sister behind her, and the pair play and walk and check on the crops until its nearly dark.

By the time she returns home, the elders are gone and her father and stepmother seem happy. She assumes theyd simply enjoyed catching up with their friends. They dont mention the meeting and she doesnt ask its none of her business.

Three months later, they throw a special lunch feast for the family and their friends. Along with the traditional spicy vegetable wat and injera, theres chicken and eggs, and the special festival Ethiopian wheat bread himbasha, with sesame seeds and cardamom, scored with a decorative wheel pattern on the top. Mamitu is looking wide-eyed at the lavish spread in front of her when her father calls her over. This is a feast being held in her honour, he informs her. Its to announce her engagement to be married. She is just 13 years old.

It had all been decided at that meeting with the elders. She is to marry a young man from the nearby village of Work Amba, 12 kilometres away. The elders may have noticed her when she was fetching water one day, or going to the market, and felt she looked ready. Theyve also checked with both sets of parents back five generations to make sure the couple arent related in any way. So now Mamitu will marry in four months time, when she turns 14. Her fianc will be 25.

Mamitu is devastated. She doesnt want to get married she isnt ready for all that entails. She doesnt want to leave her family, either, and especially her father, to go and live with an unknown man shes never met with a family she doesnt know. She starts to sob and, once she starts, she cant seem to stop. It doesnt occur to her to complain. Although her name, Mamitu, comes from the all-powerful Mesopotamian goddess of fate, who was said to decree the destinies of her people according to her whims, this Mamitu has no say at all in how she wants to live her own life. She has to obey her father. Thats just the way things are.

Her father smiles at her fondly. Its only natural shes nervous, he tells her. But her intended, Habtyimer Kebede, is a good man, and his parents are respectable, kind people. They have said they will give the couple two cows and an ox for their wedding present. He himself will give them one cow and one ox. Its a culture where no dowries are paid, but both sets of parents give more or less equal gifts to the newlyweds, and three cows and two oxen is a very good start in life for a couple. She is lucky to be part of such a match.

She can barely hear him through her tears but nods and holds her head down so he wont see the fear in her eyes as he slips a silver ring on her finger to mark her engagement.

*

During Italian rule, infrastructure was built in Ethiopia to connect major cities and dams were constructed to provide power and water, and, under Haile Selassie, slavery was officially abolished. But while so many aspects of life are changing, the tradition of child marriage isnt one of them. Matches are made by young girls parents, especially in poor rural areas in Amhara, to cement social ties and stature, and a daughters marriage represents success and respectability. It is important too that it be done while shes still a virgin. A daughter becoming too old for marriage confers shame on her family.

Economically, a child bride also means the transfer of the financial burden of caring for the girl to her new husband. There will now be one fewer mouth to feed for the girls family and more room at home for the other children. In addition, the ceremony itself and the celebrations are a good way of demonstrating her parents respectability and proper adherence to custom in the eyes of their neighbours. This is the way things have always been done, since the beginning of Ethiopian civilisation. The weight of history is behind it.

Ethiopia has long had one of the highest rates of early marriage in the world, and Amhara records the very highest in the nation, with 82 per cent of girls becoming child brides. Marrying so young isnt considered an issue among those keeping up the old ways.

No one talked about human rights 60 years ago, says a good friend of Mamitus, Barbara Kwast. Marrying so young was just something that happened. No one there thought to question it.

Girls should be happy to have a good husband found for them, and it was a way of fulfilling every womans destiny to have a family of her own. And if parents were careful to choose a boy from an upstanding family, who was to say an arranged marriage wouldnt be a good one?

This ancient kin-negotiated tradition is quite at odds with the way Ethiopia is rapidly modernising in other areas. The country is being recognised as a nation of much more importance to the outside world. Selassie caused a stir back in 1924 when he undertook his first foreign tour after joining the League of Nations, accompanied by a private zoo of six lions, four zebras and an entourage of 30, but now, he has a more serious role to play. Three years before Mamitu was betrothed, General Josip Tito of Yugoslavia made his first visit to see Selassie after splitting with the USSR. The two leaders had much in common, both having fought fascist aggressors Tito leading the partisan movement in World War II and Selassie against Mussolinis Italy. Both, as a result, were intent on building relations with countries that werent part of the two existing Cold War blocs. The world was watching keenly and the mission ended in the formation of the powerful Non-Aligned Movement, the third biggest global alliance. Then and now, newly independent African nations make up the bulk of its members, which put Selassie at the head of a crusade towards Pan-African unity. Ethiopia is attracting increasing attention from the outside world, particularly as Cold War positioning and alignments are being constantly redrawn.