Contents

Guide

CONTENTS

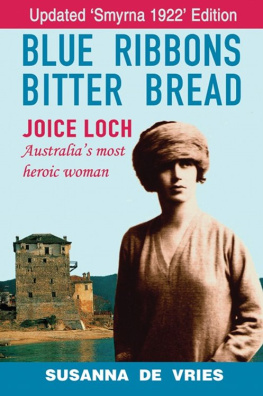

To Marusia McCormick, whose ideas and office organisation have been invaluable; to my literary agent, Selwa Anthony; to Barbara Ker Wilson and Veronica Miller for editorial assistance; to the staff of BRISQ at the State Library of Queensland; to Sir William Deane, former Governor-General of Australia, and to Elvie Munday of the Churchill Memorial Trust for details on the life of Dame Roma Mitchell; to the Hon. Peg Lusink for details on Joan Rosanove; to Professor Sir Frank Calloway, CMG, GBE, and Deirdre Prussak for help with the chapter on Eileen Joyce; to Joyce Welsh for details on Joice Loch and to publishers Hale and Iremonger for permission to use Joice Lochs story as told in my biography Blue Ribbons Bitter Bread; to the pictorial staff at Canberras National Library and Graham Powell and Valerie Helson in the National Librarys Manuscript Department, which archives my research. Thanks to Sir Laurence Street on behalf of the Street family, for permission to use the cover portrait of Jessie Street; Nancy Bird Walton and Father Paul Gardner for their cooperation and to Stuart Abrahams of the Hamlin Fistula Trust, and the Mary Ryan Bookshop for launching the book. And finally, huge thanks to my husband, the late Jake de Vries, who as an architect provided valuable insights into the career of Florence Taylor, Australias first woman architect, and also did some of the photography. Without his help this book would not have seen the light of day.

T hese stories of twenty-nine significant women reflect the changing role of women in Australia from pioneering days to the present.

To realise just how much life has changed for women today look at those faded photographs of the colonial and Federation eras. They show the master of the house, resplendent in mutton-chop whiskers and Sunday suit, standing proudly beside his wife and row of children with ringlets or well-brushed hair. The housewife or Angel of the Hearth sits passively, her latest babe on her lap, careworn and exhausted. The message conveyed by many of these family photographs is of the male as breadwinner and dominant member of the household, who makes all the decisions. And so he did in most cases. Property and children belonged to the husband; the wife was nothing but a chattel. Divorce for most women in abusive marriages was impossible. If divorced by her husband for desertion or adultery (his was allowable, not hers) she was entitled to absolutely nothing but a sewing machine.

By the 1890s, the British Married Womens Property Act enabled married women to inherit or earn money in their own right. This was later incorporated into various Australian state laws, helpful to those who had money to inherit or could find suitable work. Yet with or without this assistance, women so often rose creatively to meet their circumstances or challenge the male-dominated institutions that defined them so narrowly.

In the colonial and Federation eras, marriage was the only career available to the majority of women. Both church and state regarded sex on demand as a husbands right. Women were constantly reminded that Australia needed populating and it was their duty to have children.

In the colonial era, any woman not married by twenty was deemed to be on the shelf, and a great many girls married when they were still in their teens. Stories in this book reveal how Alice Joyce, mother of pianist Eileen Joyce married at twelve; Mary Richardson, mother of the writer Henry Handel Richardson, married at sixteen; Enid Burnell (the future Dame Enid Lyons) married Australias future prime minister Joseph Lyons on her seventeenth birthday.

Passionate seventeen-year-old Sarah Miles Franklin was urged by her mother to marry as soon as possible. Instead she wrote a novel that highlighted the injustice of boys being given an education while girls were expected to marry young and raise large families. In 1901, Miles Franklin ironically titled her first novel My Brilliant Career to highlight the fact that, in the year of Federation, any career other than marriage was nearly impossible.

This was a period when young women could not travel around unchaperoned and were expected to cover their knees and ankles at all times, as the sight of a well-turned ankle might inflame the passions of men. Women in Australias cities were even forced to swim at specific hours or in segregated pools. In 1907, Annette Kellerman risked a jail sentence by cutting the knee-length skirt off her bathing costume when trying to break a long-distance swimming record, thus asserting womens rights to wear suitable clothes for sport.

In Ancient Greece women were routinely stoned to death if found inside the sports arenas where the Olympic Games took place. When Baron de Coubertin revived the Olympic Games in Europe in the late nineteenth century, he allowed women to watch, but did not permit them to compete. He quaintly believed women should not be allowed to perspire in public. In 1908, the Baron finally relented and allowed women to compete in the archery competition. At the 1912 Stockholm Olympics, women were permitted to compete in swimming events for the first time and, against overwhelming odds, Australias determined Fanny Durack won Olympic Gold, a major landmark for women in sport.

Nellie Melba had to fight with her father to be allowed to sing on concert platforms, made more money from the stock market than from her golden voice, married and divorced, then fell in love with the heir to the French throne but could never marry him. Melba had a good business brain and acted as her own manager and publicity agent. Having felt initially exploited, she was one of the first women in the world to market her own talents to maximum effect.

Other memorable stories in this book are those of talented Florence Taylor, Australias first woman architect; the equally feisty Nancy Bird Walton, Australias first woman commercial pilot; and Dame Roma Mitchell, Australias first woman high court judge and state governor. Reading about these dedicated, talented and compassionate women will make you laugh, weep and wonder at their bravery and determination.

This book tells the story of women who demanded something different from the restricted lives of their mothers and grandmothers. It becomes apparent that gaining the right to vote (as a spin-off from Federation) did not change womens lives nearly as much as Vida Goldstein and Catherine Helen Spence and other intrepid campaigners for female suffrage had hoped. In fact gaining the vote had very little effect on the life of the average Australian woman, as married women on the whole voted the way their husbands told them to. For twenty years not one single woman entered Parliament Edith Cowan being the first woman to do so in 1921. When this happened, a male journalist accused her of neglecting her home and family, even though Ediths youngest child was thirty! The introduction of vacuumcleaners, domestic refrigerators, piped water and tinned foods did considerably more to liberate women than did the right to vote or to sit in parliament.

Enid Burnell (the future Dame Enid Lyons) battled male prejudice to become Australias first female Federal Cabinet minister. In her first decade of marriage, Enid suffered severe pain from an undiagnosed pelvic disorder while coping single-handedly with six children under the age of ten, mountains of housework and no money to employ help. Her husband, Joseph Lyons (at that stage a member of the Tasmanian Government at a time when politicians were poorly paid), was away from home most of the time. Between doing the household chores, which included a huge weekly wash without a washing machine, Enid wrote her own and her husbands speeches and complained No man would put up with this kind of life.

Next page