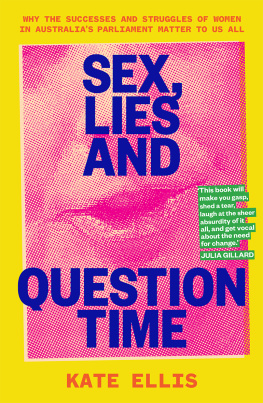

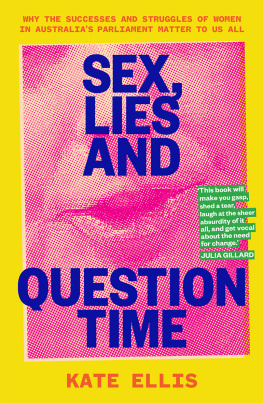

THERE ARENT MANY times when you get to witness the world changing before your very eyes. I clearly remember the difference it made when Julia Gillard became the nations first female prime minister. As a member of parliament, I used to regularly visit the schools in my electorate and ask students to put up their hand if they thought they might be prime minister one day. As soon as Julia became prime minister, an army of girls would enthusiastically raise their arms. At community meetings parents would bring along their young daughters and explain how they were interested in running for parliament one day. An inspired generation of girls was emerging and seeing the world of possibilities available to them. It was such an obvious and palpable change that tears of joy welled in my eyes whenever I witnessed this wave of young women who were going to stand up and change the world.

This is how it should be.

But it didnt last. Attention soon turned to the overtly sexist and misogynistic treatment Gillard received as prime minister. In the years that followed the headlines were full of controversies that raised new questions about why on earth any woman would want to go into politics.

Sarah Hanson-Young spoke out about being slut shamed in the federal parliament after she was told to stop shagging men; Julia Banks and Lucy Gichuhi both publicly alleged that bullying of women was commonplace in our political institutions; Emma Husars career as an MP ended following unsubstantiated sexual allegations; and Julie Bishop was overlooked by her colleagues as a leadership candidate in favour of men who were far less popular with the general public. These are the stories that reached the public and dampened the mood of optimism and inspiration that had emerged all too briefly with Gillards ascension in 2010.

By 2017 a Plan International Australia survey showed that zero per cent of the young women aged eighteen to twenty-five surveyed would consider entering politics as a future career. Zero. The most recent follow-up survey in 2019 showed that 90 per cent of young women still believed Australian female politicians were treated unfairly.

One of the things I find most jarring about this is that the almost fifteen years I spent as a member of Australias House of Representatives were easily one of the most amazing experiences and greatest privileges of my life. I will never again hold a job that is as rewarding, interesting and inspiring as being a federal MP. I dont want a generation of women turned away from that opportunity. And I dont know that we are necessarily giving these young women a clear and full picture on which to base this decision.

The key question, though, is how will we ever get enough women into our parliament if the perception remains that politics is hostile to womens interests, womens needs and womens lives? And how does that impact the nation more broadly? A parliament that is not representative of our wider community is never going to be best able to select, address and prioritise the issues important to us all.

Since I retired from federal politics at the 2019 election my belief has only strengthened that we need more women fighting in our parliament to ensure that issues affecting all women in Australia are at centre stage. We continue to see women and children killed with devastating regularity across Australian cities and towns. We see women disproportionately shouldering the burden of the impacts of COVID-19 and facing a lifetime of disadvantage as a result. After an all too brief experiment with free and accessible childcare we have now returned to the outdated and fragmented childcare funding model, despite overwhelming evidence of the constraints this places on womens economic participation. Women make up over half of our population and we need their voices to be heard on issues across the board, from economic decision-making to policies on climate change and immigration. And its not just about hearing their voices but also ensuring that their attitudes, their management and leadership styles and their interests are fairly represented.

At a time when we have a critical need for strong women fighting for reform on the issues that matter, we have thousands of young Australian women turning away and not even considering entering politics.

When I was an MP, my press secretary would sheepishly approach me with a request to speak about my experience as a woman in politics, already knowing full well what my answer would be. It was always no. Many of my female colleagues say the same thing.

I always felt very strongly that my job was to speak about the community that I was elected to represent. Not myself. We fight elections on issues and policy solutions and values, not so that we can be commentators on our own profession. It just seemed self-indulgent.

An even bigger reason I turned those offers down was that I am aware of my privilege. Mine is not a sob story. The issues faced by women in Australian politics are first world problems. We are women who are highly paid, who have access to power and who have a voice and a platform from which we can wield that power. If we want to focus on womens issues there are many other matters that are a far greater priority. Our job is surely to fight for those living in crippling poverty or sliding into homelessness, those facing sexual assault, domestic violence and being killed each week at the hands of men, those who are unsafe and helpless without any avenue to a fair and just existence. Of course we want our elected MPs focusing on these issues, and not on themselves.

So, in breaking the habit of a lifetime, in the pages that follow I write about the real-life experience of being a woman in Australian politics. This is not an academic thesis. It is an insiders account of what I experienced in the years I had the privilege of serving in the parliament, and a reflection on the fact that while I am grateful for every second that I served, there are some things that happen to women that just should not occur, there are some things that we face disproportionately compared to the men we work alongside and there are some things that we need a broader public discussion about.

It is also a collection of firsthand insights from women who have served in our parliament. Over the past year, I interviewed a number of women from different political backgrounds about key issues women face in parliament. Some interviews were much longer and more personal than I had expected. Some were short and over the phone. Despite having worked alongside many of these women for years, I wanted to understand more of their lived experience: the good, the complicated and the hard parts of their daily realities. I am tremendously grateful to all the women who spoke so openly and honestly with me about their experiences and insights. I am also very aware of the number of amazing women who have made remarkable contributions who I did not speak to in this process. Those achievements are not unnoted.

Politics is a tough game for both men and women, but the obstacles and attacks that women often face are different. As Penny Wong told me, What is different for women in politics? Any woman who has achieved a position of significance has been subjected to different standards of behaviour to those which would be expected of men. Sometimes that has been more and sometimes it has been less. That disparity has been greater for some women than others. But there is still always a difference.

Different methods are used to undermine women. Different standards are set for women. Different attention is paid to the appearance and private lives of women. Different levels of respect and recognition are paid to the achievements of women.

Next page