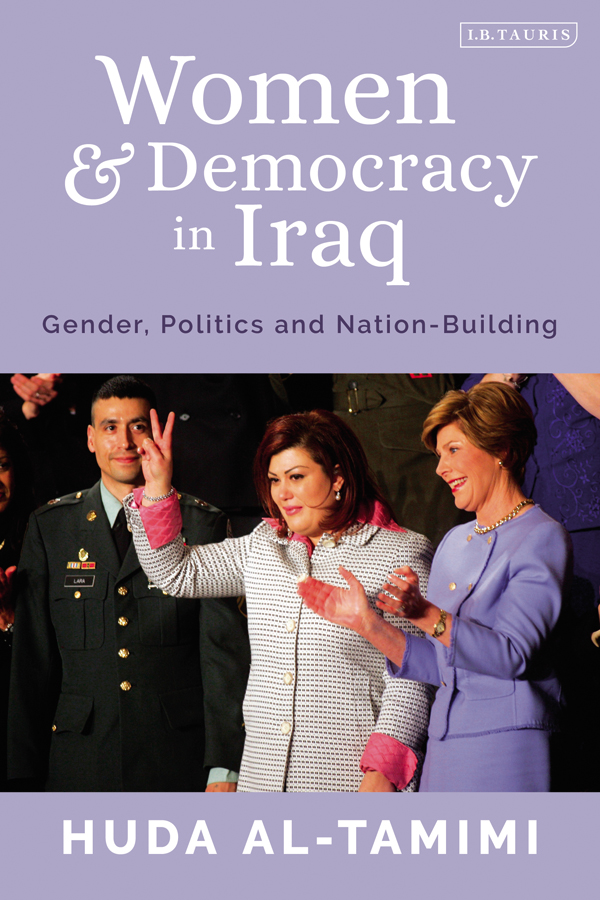

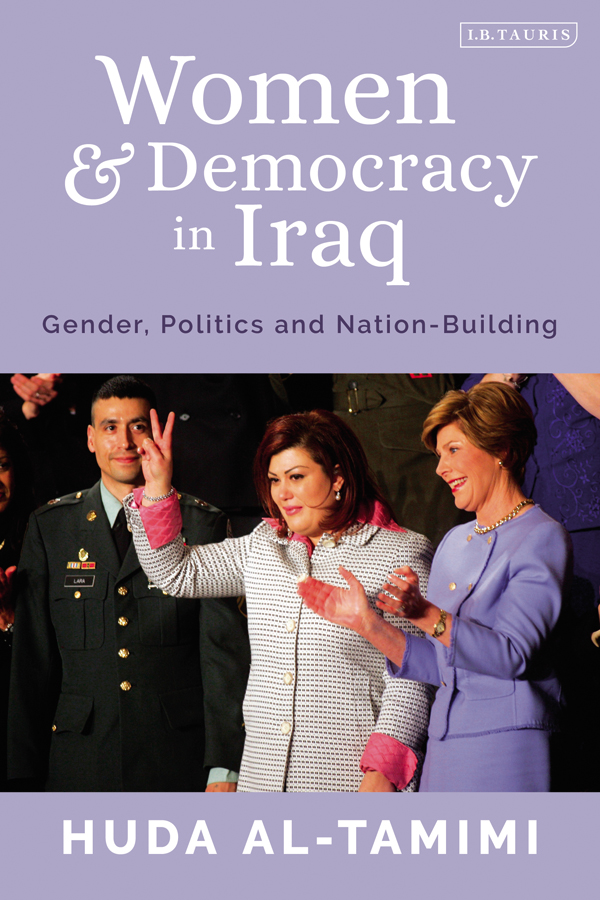

Women and Democracy in Iraq

Women and Democracy in Iraq

Gender, Politics and Nation-Building

Huda Al-Tamimi

I.B. TAURIS

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK

1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA

BLOOMSBURY, I.B. TAURIS and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published in Great Britain 2019

Copyright Huda Al-Tamimi 2019

Huda Al-Tamimi has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work.

For legal purposes the constitute an extension of this copyright page.

Cover design: Adriana Brioso

Cover image: Iraqi voter Safia Taleb al-Suhail during the State of the Union address, Washington, DC, 2005. ( PAUL J. RICHARDS/AFP/Getty Images)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers.

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third-party websites referred to or in this book. All internet addresses given in this book were correct at the time of going to press. The author and publisher regret any inconvenience caused if addresses have changed or sites have ceased to exist, but can accept no responsibility for any such changes.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN: 978-1-7883-1280-6

ePDF: 978-1-7883-1622-4

eBook: 978-1-7883-1623-1

Series: Library of Modern Middle East Studies

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com and sign up for our newsletters.

This book is dedicated to the women of Iraq: may their voices be heard.

Contents

This book would have not been possible without the support and encouragement from those who have contributed directly or indirectly to my work. I am especially grateful to my husband, Dr. M. Al-Hindawi; my daughters, Dr. Zain Al-Hindawi and Dr. Yasmeen Al-Hindawi; my son, Dr. Ahmed Al-Hindawi; and my granddaughter, Sara Hindawi Thompson.

I also owe much to my mentor and colleague Professor James Piscatori, who took an interest in the book from early on and gave me encouragement and support through its various stages.

I am fundamentally indebted to I.B. Tauris, particularly Dr. Sophie Rudland and the readers to whom the publisher sent my manuscript and whose comments, both critical and appreciative, helped clarify and refine my thinking. I am grateful to Lisa Vera, whose meticulous editing improved the manuscript in numerous ways and whose dedication and enthusiasm certainly made labor preparing the manuscript for press far more enjoyable than it might have been.

Ever since the region that is now modern Iraq first came under Ottoman the rationale turned to the need to depose the Iraqi president Saddam, whose Baathist regime was accused of state-sponsored violence and political persecution of the Iraqi people for more than two and a half decades.

While the regime change sparked by US-allied forces in Iraq was met with outrage among certain segments of the Iraqi and international communities,

As the post-invasion

The 2005 Constitution granted women at least nominal equality with men, retaining an article that has been in place since the Baathist Provisional Constitution was adopted in 1970: Iraqis are equal before the law without discrimination based on gender, race, ethnicity, origin, color, religion, creed, belief or opinion, or economic and social status (Article 14). The 2005 Constitution extended this formalized statement of gender equality into the political sphere: The citizens, men and women, have the right to participate in public affairs and to enjoy political rights including the right to vote, to elect and to nominate (Article 20). Although the transition to democracy has been characterized by sectarian conflict and increased violence toward women, the new constitution also has offered the promise of an unprecedented formal political role for women in the Iraqi Parliament.

After the new constitution was ratified, parliamentary elections in 2005, 2010 and 2014 resulted in 31.5 percent, 26.1 percent and 25.3 percent of parliamentary seats being awarded to women, respectively.

While those statistics suggest great strides for womens political participation, the current literature is largely silent about the extent to which Iraqi female politicians have been empowered by greater representation. The study of gender quotas stipulates that the inclusion of women in governing institutions is critical, as gaining parliamentary seats is not an end in itself, but rather a means for participating in authoritative decision-making that determines how a society functions. The achievement of gender impartiality in post-conflict countries and insuring democracy in the long term depend on many elements comprising the progress of a democratic political culture, the level of mobilization of women in civil society, and the clearness and reliability of democratic establishments.

In this sense, quota scholars Ballington

A further distinction may be drawn in the form of symbolic representation, a term that refers to the legitimacy of political institutions and their representatives as perceived by the constituencies being represented.

Given that multiple schools of thought align gender justice with democracy, it is important to delineate the difference between Western democracy and the notions of reformers in the Arab world. This distinction must by definition take into account the influences of Islam, as religion has been highly politicized and deeply ingrained into Iraqi social and cultural frameworks. Any articulation of Islamic democracy must be premised on the acceptance of tawhid; that is the conviction and witness that there is no God but God and at the core of the Islamic religious experience stands God Who is unique and Whose will is the imperative and guide for all. Although in the Iraqi context greater opportunity now exists for women to influence public policy via the political process, the formal gender equality of political engagement remains elusive. That aside, Iraqi women have a long tradition of political activism and participation in their countrys affairs, even though their mobilization in formal political roles has languished throughout history.

This book aims to explicate the avenues by which Iraqi women gain and hold parliamentary positions under the electoral gender quota, the extent to which they do influence policy change and their personal experiences while serving as public agents. By illuminating the processes by which Iraqi women are mobilized in Parliament and the subsequent outcomes for women, this research responds to the challenge promulgated by Childs and Krook. The book evaluates Iraqs progress toward eroding gender-based discrimination and considers its potential to identify future opportunities for women to engage effectively in the political and social advancement of their gender.

The role of women in politics is important to consider when characterizing a countrys developmental and gender-egalitarian

Both men and women in the Middle East have become increasingly politicized since the beginning of the twentieth century.

Next page