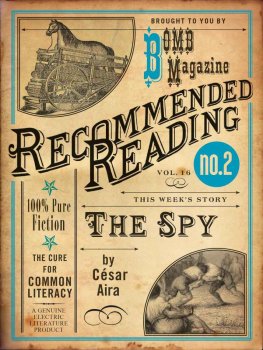

A BOMB IN

EVERY ISSUE

ALSO BY PETER RICHARDSON

American Prophet: The Life and Work of Carey McWilliams

A BOMB IN

EVERY ISSUE

How the Short, Unruly Life

of Ramparts Magazine

Changed America

Peter Richardson

NEW YORK

LONDON

2009 by Peter Richardson

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher.

Requests for permission to reproduce selections from this book should be mailed to: Permissions Department, The New Press, 38 Greene Street, New York, NY 10013.

Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2009

Distributed by Perseus Distribution

ISBN: 978-1-59558-546-2

CIP data is available

The New Press was established in 1990 as a not-for-profit alternative to the large, commercial publishing houses currently dominating the book publishing industry. The New Press operates in the public interest rather than for private gain, and is committed to publishing, in innovative ways, works of educational, cultural, and community value that are often deemed insufficiently profitable.

www.thenewpress.com

Composition by dix!

This book was set in Bembo

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

In May 1962, a magazine was born. Published in suburban Menlo Park, California, it described itself as a forum for the mature American Catholic focusing on those positive principles of Hellenic-Christian tradition which have shaped and sustained our civilization for the past two thousand years. Its first issues debated the moral shortcomings of J. D. Salinger and Tennessee Williams. According to one designer, it looked like the poetry annual of a midwestern girls school.

By 1968, the magazine had moved to the bohemian North Beach neighborhood of San Francisco, added generous doses of sex and humor, adopted a cutting-edge design, forged links to the Black Panther Party, exposed illegal CIA activities in America and Vietnam, published the diaries of Che Guevara and staff writer Eldridge Cleaver, and boosted its monthly circulation to almost 250,000. A Time magazine headline from that periodA Bomb in Every Issuedescribed its impact. Seven years later, it was out of business for good.

What happened?

This book recounts the short, unruly life of Ramparts magazine, the premier leftist publication of its era. It features the magazines outsized characters and explosive stories, the political movements that transformed it, and the fractious energies that destroyed it. Although it places Ramparts in its Bay Area milieuthe student movements in Berkeley, the rise and fall of the Black Panthers in Oakland, and the acid-inflected Summer of Love in San Franciscothe story is by no means a local one. Ramparts changed national media and politics, not only with its stories on civil rights, Vietnam, black power, and the CIA, but also by demonstrating that mainstream media techniques could be used to advance leftist politics. That precedent would fuel progressive journalism for a generation.

As a publication, Ramparts was unique. Its combination of radical content, sophisticated design, and public relations savvy distinguished it from its stodgier East Coast counterparts and grittier underground ones. Its investigative stories helped revive the tradition of muckraking, earned it a Polk Award for excellence in magazine reporting, and influenced a generation of young journalists as well as national leaders. After Martin Luther King Jr. saw a Ramparts piece on napalmed children in Vietnam, for example, he decided to speak out against the war for the first time. That side of Ramparts, former contributor and sociologist Todd Gitlin remarked later, walked on solid ground. In a recent interview, former Ramparts staff writer William Turner summed up the magazines legacy this way: When you look back on it, where else would those articles appear? The Saturday Evening Post?

At its peak, Ramparts was both a platform and a seedbed for a generation of reporters, activists, and social critics. Its contributors included Noam Chomsky, Seymour Hersh, Bobby Seale, Tom Hayden, Angela Davis, Susan Sontag, William Greider, Jonathan Kozol, and a young Christopher Hitchens, who wrote for Ramparts under a pseudonym. More surprising, perhaps, was the magazines Washington, DC, contributing editorBrit Hume, the Fox News host and anchor. Two Ramparts writers left to create Rolling Stone, and three editors decamped to found Mother Jones. On the literary side, the magazine ran work by Kurt Vonnegut, Jorge Luis Borges, Gary Snyder, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Ken Kesey, Erica Jong, and Gabriel Garca Mrquezseven years before Mrquez was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature.

Ramparts also represented an ethica deeply irreverent one. Although it covered Vietnam, CIA torture, and other grave issues, Ramparts maintained a humorous, even playful tone. Over and above its youthful desire to challenge political authority, Ramparts called attention to the stupefying effects of that authority on the media itself. It famously critiqued the Warren Report and then reviewed a fake book on the Kennedy assassinationin the same issue. When the faux review generated an avalanche of media calls and citations in serious publications, the staff was delighted. Like all good satire, the review demonstrated a mastery of the targets methods; but the response also confirmed the flatfootedness of the mainstream mediathe very reason the satire was required in the first place. In this sense, the magazine consistently worked at another, more reflexive level. In addition to breaking big stories, Ramparts entertained readers, mirrored the New Lefts fascination with the media, and exemplified new possibilities for American journalism.

Certainly the magazines short life and current obscurity should figure in any evaluation of its achievement. Ramparts wasnt the Nation, Harpers, or the Atlantic, whose histories stretch back to the days of Mark Twain and Henry James. At its flashpoint, Ramparts was something else altogether: the journalistic equivalent of a rock band, a mercurial confluence of raw talent, youthful energy, and high audacity. Its sheer incandescence blew minds, launched solo careers, and spawned imitators. It was born, lived, bred, and died. Because it was mortal, not monumental, genealogy may be more important than longevity in understanding its significance. If so, Ramparts should be judged not only by what it published, but also by the subsequent work it made possible. By this measure, it accomplished a great deal.

Ramparts figures regularly and sometimes prominently in other histories, but few books have focused on its own brief, turbulent life. The most sustained treatment is Warren Hinckles If You Have a Lemon, Make Lemonade: An Essential Memoir of a Lunatic Decade. Having worked as Ramparts promotions director, editor, and publisher, Hinckle was perfectly positioned to deliver the inside story, and his book offers a picaresque version of the magazines early period. But Hinckle drops the narrative in 1969, the year he left Ramparts, and the books 1974 publication date precluded a discussion of the magazines long-term influence.

Perhaps the best-known portrait of Ramparts can be found in Radical Son, former editor David Horowitzs memoir. Thanks to that book, Ramparts is remembered mostly for its prodigious spending, high-handed editorial practices, chaotic management, and ideological zeal. More hauntingly, Horowitz also recounts the murder (purportedly by Black Panthers) of former

Next page