Say thank you to the mothers who sent their sons to help us. They will never fully understand how much it has meant to us. But hopefully they will understand just a little.

Gulaley Sherzad, leader of the womens centre in Gereshk

While it is estimated that women perform two-thirds of the worlds work, they only earn one-tenth of the income, and own less than 1 per cent of the worlds property.

UNICEF, Gender Equality The Big Picture (2007)

NARGISS AND THE GUNS

The first time I meet Nargiss, she comes with another woman Ive known for some time. Together, they have driven thirty kilometres through an area crawling with highway robbers to meet with me at a military base.

Nargiss is young, pregnant and beautiful. She is also afraid of the Taliban. She covers her smile with her hand because she is unhappy about her teeth, and she says almost nothing at all. She drinks my tea, eats my cake and sneaks leftovers into her pocket.

The second time I meet Nargiss, I understand why she has sought me out. Some months before, Nargiss gathered the women of her village and formed a cooperative to manufacture handmade jewellery. The colourful beads they use come from Pakistan. They weave the yarn themselves. For the first time, these young women are earning their own money. The Taliban dont want women to work. But the men in Nargisss village are supportive.

I would like you to help with my project, just as you help the other women. But that is not why I am here, she tells me.

Nargiss is still shy, yet the way she speaks indicates that she is a strong woman determined to take care of herself. She makes it clear to me that she is not dependent upon my help, but that she is here to tell me something.

The Taliban have begun running arms through her village and Nargiss wishes to pass on the information. Nargiss wants the Taliban out. Later, her opposition to the Taliban will cost her dearly.

Nargiss is one of a score of women I get to know during my first tour of duty in Afghanistans Helmand Province. The women will end up changing my life, and I theirs.

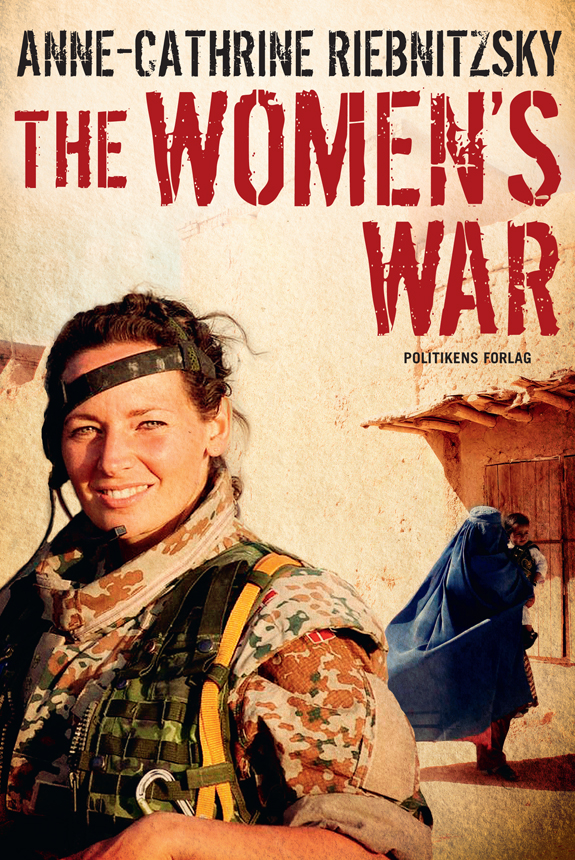

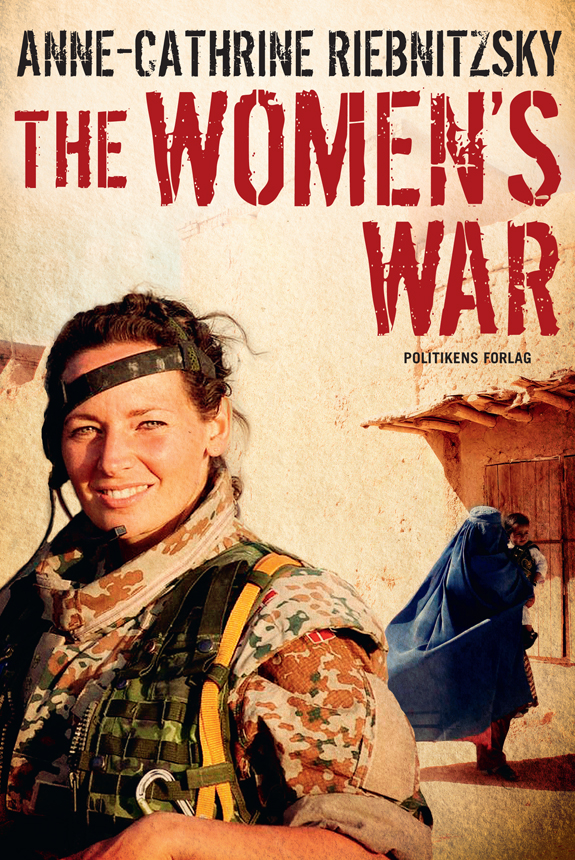

This book has been written because I promised the women of Gereshk to thank the mothers of the Danish soldiers stationed there, but also because I feel something important is missing from the domestic debate on Afghanistan, something that cannot be encapsulated in a three-minute story on the evening news.

Afghanistan, and Helmand in particular, have been part of my life for more than four years. In 2006, my then partner was sent to Helmand with ISAF 1. Being left behind was hard. Support for the soldiers was almost non-existent and politicians were indecisive.

In August 2007 I went there myself as an officer with ISAF 4. My personal hope was in some way or another to be able to help Afghan women. During six months I formed bonds with women who were very often alone. Surviving as a widow and a mother of six is no mean feat when youre forbidden to work or mind a shop.

Following my tour and a short period at home in Denmark, I was asked by the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs to return to Helmand as a civilian adviser. I jumped at the chance. This time, I stayed for eight months.

With this book I hope to be able to pass on the thanks of women I know and for whom I have developed profound respect. I hope, too, that my personal experiences as described on these pages will provide insight into what may seem distant but which nonetheless impacts heavily on families in Denmark and elsewhere every time a son, daughter, brother, sister, friend or partner travels to Helmand to do a job of work.

The book represents my own experiences. All the incidents described in it are true and occurred in the chronological order in which they are set down. In the interests of the personal safety of some of the women involved, a few names have been changed or left out completely. Other women appear under their own names. These are women whose faces have already appeared on electoral posters and who for this reason already live under the threat of death at the hands of the Taliban. Publication of this book will neither heighten nor lessen the experience of those threats.

My book is of course by no means the whole truth about Afghanistan. But it does describe a part of that truth otherwise seldom told by domestic media.

Anne-Cathrine Riebnitzsky

PART I

CHAPTER ONE

FROM HOME TO HELMAND

Im going to take sixteen X-rays now inside your mouth.

The woman in the white coat in the dental clinic of Denmarks Varde military base bends over me to explain.

For identification, if anything should happen and more than one of you get hit at once. Armoured cars going over landmines, roadside incendiaries, that sort of thing.

I nod, unable to say anything with my mouth full of plastic. It takes over half an hour to X-ray my teeth. The teeth my dentist finds worthy enough to send to Helmand.

I mull over what she has said. Theyll need to identify me among other bodies blasted to pieces. Thats what she has said, only in a nicer way.

Its August 2007. Im driving my sore mouth back across Denmark to Copenhagen. The occasional combine harvester crawling up the gentle hills, devouring corn. I sniff in the scent of summer and fresh straw.

My parents never argued during harvest. The years earnings were rolled in, and in the smell of it all was a sense of hope and opportunity. Now, again, its a smell that fills me with a profound sense of happiness, and yet somewhere beneath it all is a tinge of sadness. Harvest doesnt go on.

Beyond the yellow fields, the sea is clear blue. I grew up by the sea, am struck afresh by its changeability. I try to take in all the blue with my eyes so I can remember it forever.

Im looking forward to leaving. At the same time, everything else becomes more sharply defined, because I know I have to leave it.

Back home in my apartment in the capitals multi-ethnic Nrrebro district, I begin to fill in the standard form: my last will and testament. They need to know what I want to happen in case of severe injury, and how my funeral should be organized if I get killed.

The last point urges us to write to our next of kin: a last goodbye in case we never see each other again. I think about my parents, my mother in particular. I think about my younger brother for a long time. I think about my girlfriends and my ex-boyfriend, with whom Im still in love.

I think about my funeral. Inside the church is a coffin, and on the pews are all my friends and my parents. I see their faces before me. Some of those who have turned up are people I havent seen for a long time. My girlfriends are overcome with grief and cant understand why it had to be me who died.

I cry. Tears fall on to the forms. I dont want to die. I really dont want to die.

Yet amidst it all is a sense of calm. I think through my life. I think of all the things I have achieved and all the people I have known. Theres a sense of satisfaction there. Few regrets. Not much I wanted but never got round to doing. The only thing I need is more time.

Take care of me, God, I whisper. Take care of my mum and dad, and my brother.

I take a deep breath. I still feel its the right thing to do. Im going to Helmand.

So far Ive enjoyed a brief and intense career as a language officer in the Danish Armed Forces. Ive done interpreting at home and abroad, but have never been on a real mission. For some time now Ive found it frustrating to teach soldiers about managing meetings, body language and cultural understanding without having taken part myself in the things they do. Visions of burkas and an increasing knowledge of the aims of Taliban made me think my male colleagues werent the only ones who should go to war.

Next page