ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Manal Hamzeh is a Professor of Gender and Sexualities at the Department of Interdisciplinary Studies of New Mexico State University. Dr. Hamzehs teaching and research draw on antiracist educational theories and decolonial feminist research methodologies. She is the author of Pedagogies of Deveiling ( 2012 ) and co-writer of the short animation film The Four Hijabs ( 2016 ), with playwright Jamil Khoury of Chicagos Silk Road Rising Theater.

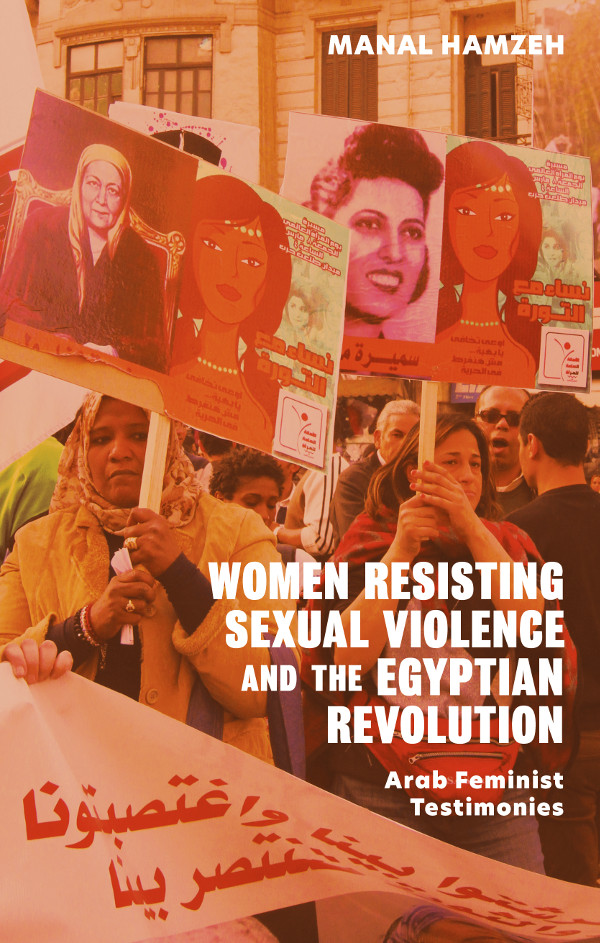

WOMEN RESISTING SEXUAL

VIOLENCE AND THE EGYPTIAN

REVOLUTION

Arab Feminist Testimonies

Manal Hamzeh

Women Resisting Sexual Violence and the Egyptian Revolution: Arab Feminist Testimonies was first published in 2020 by Zed Books Ltd, The Foundry, 17 Oval Way, London SE11 5RR, UK.

www.zedbooks.net

Copyright Manal Hamzeh 2020

The right of Manal Hamzeh to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

Typeset in Plantin and Kievit by Swales & Willis Ltd, Exeter, Devon

Cover design by Burgess and Beech

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of Zed Books Ltd.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-78699-621-3 hb

ISBN 978-1-78699-622-0 pdf

ISBN 978-1-78699-623-7 epub

ISBN 978-1-78699-624-4 mobi

To Samira Ibrahim, Yasmine El Baramawy, and Ola Shahba, who trusted me with their shahadat, and to all the Egyptian women who made suwret yanayer happen.

CONTENTS

I write here with sincere appreciation for those I love and respect, who have been generous with their collaborations and conversations with me over eight years. Those are many; first and foremost, the three women at the center of this book, Samira Ibrahim, Yasmine El Baramawy, and Ola Shahba. I have no more words, just appreciation and love for all the trust and kindness you shared with me. Alf shukur .

Special thanks to my dear friend Nadia Kamel. You have been so generous with your insights, home, food, and insightful conversations. Thank you to my cousin, Yassar, for keeping Cairo as a home and Egyptian dialect close

Huda Elsadda and Faiha Abdulhadi, thank you for your femtoring and your powerful Arab feminist scholarship.

With love, gratitude, and respect for years of friendship, the struggles of maintaining solidarity and negotiating imperial borders, and co-creating transborderly knowledges, thank you Cynthia Bejarano and Judith Flores Carmona.

Special thanks to Tabitha Parry Collins for their touches on the words and looks of the text. I am also thankful to Kim Walker at Zed Books for believing in this project and for her patience along the way.

Heather Sykes, I have no words for your unwavering understanding and limitless support. In return, I offer my humility, appreciation, and unconditional love.

This book is about the resistance of three women who experienced state-sanctioned violence during the Egyptian Revolution. Egyptian womens shahadat [testimonios]

This book is built on the shahadat of three women who were protesting in the streets during suwret yanayer and who experienced state-sanctioned sexual violence during the power transition period after suwret yanayer, which occurred between 2011 and 2012 . Three separate chapters present the shahadat of Samira Ibrahims the revolutionists.

Each shahada [testimonio] ), are at the center of this work.

The testimonial texts in this book make two main contributions: preserving and representing the powerful shahadat of women resisting state-sanctioned sexual violence after suwret yanayer. First, preserving the shahadat of suwret yanayer adds to ongoing efforts to archive the record of suwret yanayer from the revolutionists and the peoples perspectives (), rather than the perspectives of the regimes in power. Reviving and remembering this part of the Egyptian peoples collective memory of suwret yanayer is crucial. It also stems from the insistence to own and disseminate their narrative of suwret yanayer from the perspective of those who made it and are still working for its values and goals.

The shahadat by Samira, Yasmine and Ola about state-sanctioned physical and sexual violence counter the erasures of womens contribution in suwret yanayer. Their narratives challenge the normative social gendering order. Specifically, they challenge the patriarchal oppressive power of anti-revolution forces, both militarist and Islamist, in 2011 and 2012 . Their shahadat were, and still are, major interruptions to the current regimes propaganda machine that is hard at work trying to erase suwret yanayer, and particularly womens contribution to it. Hence, preserving these shahadat is an act of subversion that reflects Egyptians insistence to continue their revolution, especially since the militarists took over Egypt in 2013 (). Preserving these shahadat is an act of revolutionary resistance.

Second, as a nasawyya Arabyya [Arab feminist], .

I build on the work of Arab feminist academics who also expose the collusion of the corrupt Arab regimes with imperial powers ().

Hence, the three shahadat I represent in this book are examples of Arabyya methodologies that both represent and theorize womens bodily experiences of sexual violence and resistance. The shahadat of Samira, Yasmine, and Ola call feminists to pay attention to Egyptian womens shahadat as methodologies of resistance, healing, resilience, and imagination of a just Egypt. Samira, Yasmine, and Ola legitimize shahadat both as an Arabyya feminist methodology and as on-the-ground theorizing of resistance to gendered violence.

Before discussing the actual study that resulted in this book, I map my reasons for using Arabic names for the Egyptian Revolution of 2011 , and then briefly review the latest nasawyya Arabyya rethinking of gender during the multiple Arab uprisings since 2011 .

Naming the 2011 Egyptian Revolution

The Egyptians themselves refer to the 2011 Revolution using four main names interchangeably:

suwret yanayer [the January Revolution];

suwret khamsah ou ishreen yanayer [the January 25 Revolution];

el ttamnttashar yaum [the 18 Days];

essuwra [the Revolution].

All four names refer to the days of massive Egyptian presence on the streets that began on January , 2011 , with protests against police brutality on yaum eshurttah [Police Day],

At the same time, essuwra was used to mark the beginning of a longer period of mass protests and the dynamic process of transition that lasted two more years from February 2011 to June 2012 . This period includes the takeover of elmagles elala lilqwat almusalaha [the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF)] This term reflected how Egyptians maintained their civil disobedience, protests, and campaigning in the streets and squares of Egypt. They sustained their activism, and kept demanding radical changes to the governing regime and calling for the goals of suwret yanayeraish, huryya, adalah igtimayya [bread, freedom, and social justice].