What do you do with a place that is beautiful? Destroy it.

When I first visited the Riviera as an undergraduate twenty-five years ago, I was aghast.

I had little enough experience of the Continent, let alone gone further afield. My parents were both London doctors who rarely allowed themselves a weeks holiday a year. It was not spent abroad partly because they had little truck with foreigners, and also because it was just before the time when the British made it their habit to holiday beyond their own shores. The jet-set, those who travelled by the pioneering de Havilland Comet and the Boeing 707, were celebrities the actors Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor, the Beatles on their way out to Shea Stadium, the racing driver Jackie Stewart, Presidents Khrushchev and Lyndon Johnson. We were not.

As a consequence, destinations like St Moritz, Acapulco, Barbados, Capri, Florence and Mustique had an infinite romance and allure, Shangri-las of unattainable luxury, sophistication, glamour , culture, exoticism and romance. Brought up as I was in Bexley, Sidcup, Redhill and Croydon, they might have been Prosperos enchanted island.

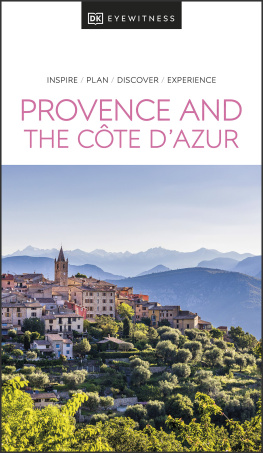

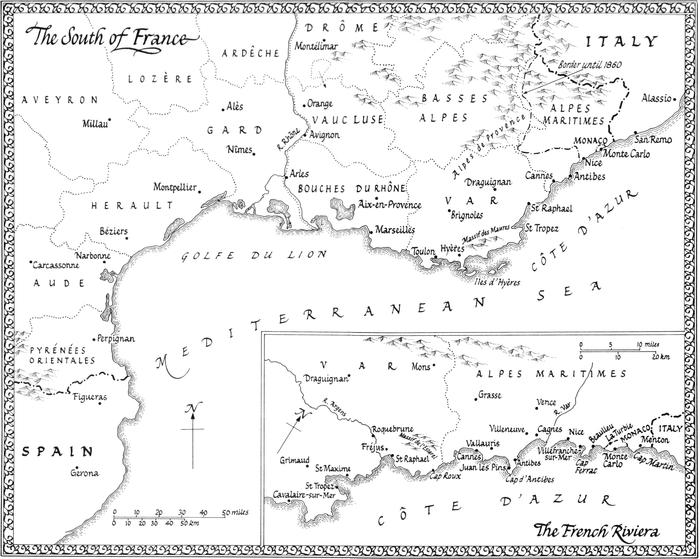

The jewel in the crown of my imagination was the Cte dAzur. Largely ignorant of French history, manners, achievements and people, I took France at its own estimate as the byword for Continental no, global sophistication, culture and taste. It was not long after President de Gaulles refusal to admit the United Kingdom into what was then the European Common Market. Paris was the capital of the worlds imagination, art, beauty, women and, of course, cuisine. No wine other than French was wine. As for the South the Riviera, the Cte dAzur it was the neplusultra of the worlds resorts: the golden chain of Monaco, Nice, Antibes, Juan-les-Pins, St Raphael and St Tropez was a Promised Land of warmth, natural beauty, hospitable people and, presumably, jolly good five-star hotels like the Hilton.

So when I eventually visited it in 1978 I was surprised by the agglomeration of tower blocks, dilapidated Edwardian hotels, estate agencies, fast-food restaurants and shopping centres that I discovered littering the hundred-mile stretch of pebble-stone beaches from Hyres to Menton and the Italian frontier. Surprised, too, by a coast that seemed little more than a strip of polluted sea, bordered by a few yards of burning human flesh, a railway and an autoroute. Surprised by the French who as I might have guessed from de Gaulle were Anglophobe, choosing to remember Napoleon, Trafalgar and Waterloo rather than their liberation at British and American hands in two world wars.

I was not to return to the Riviera for almost twenty years.

*

I was then working on a book about the contribution made by the English to the development of the Alps. Without the mountaineer Edward Whymper, the travel agent Thomas Cook, the pioneer skiers Arthur Conan Doyle and Arnold Lunn, I argued, the range today would have been little better than the East Anglian fens. Research on this took me first to the alpine resorts that, until 1939, had been virtually English enclaves: places like Wengen, Mrren, Kandersteg and Zermatt. Then I visited two resorts created by English entrepreneurs after the Second World War: Colonel Robert Lindsays Mribel in the Haute Savoie and Peter Boumphreys Isola 2000 in the Alpes Maritimes, high above Nice. As the post-war French high-altitude resorts, like Flaine, Courchevel and Val dIsre, represented some of the worst acts of architectural vandalism ever perpetrated in the Alps, I wanted to see if the English had managed any better. As I discovered in the course of my 1997 trip, they had not.

From Isola I drove down into Nice. On this occasion my expectations of the city were low, and not much about it surprised me. True, its setting between the Alpes Maritimes and the azure sea was incomparable, and the labyrinthine old town had a vitality, character and pleasing squalor of its own, a sort of Soho-en-Mer. But other than that and the weather, what with its stony beach and bellepoque hotels, it was reminiscent of Brighton. Two things surprised me, though: first, the people the concierge in my hotel said that the Riviera attracted more than eight million visitors each year and, as far as I could see, they were all in Nice and second, that the palm-fringed motorway along the front was named Promenade des Anglais. The English made the Alps: had they made the Riviera too?

I had a book to finish and I cannot say I troubled myself much with the question then. In due course, though, the paradoxes of the coast began to interest me. As cursory research suggested not least in Patrick Howarths WhentheRivieraWasOurs it was indeed foreign tourists rather than the French who had developed the coast. The English were prominent among them, subsequently the Russians and the Americans. The locals did not reclaim their own coast until after the Second World War. As for the huge popularity of a destination that by any rational estimate was decades past its sell-by date, grossly polluted and spoiled, that was a puzzle and the second paradox. What was it about the Cte dAzur that made it a Shangri-la?

Of the Alps, Arnold Lunn wrote: Men lifted up their eyes to the hills to discover the spiritual values which were clouded by the smoke and grime of the industrial revolution. It was difficult to imagine that Victorian Englishmen would have felt the same about the Riviera. What had attracted them to the coast? What had they done to develop it? And what continues to attract people from all over the world to it in such numbers?

In trying to answer these questions I have not attempted to write a comprehensive social or, indeed, Social history of the coast. Rather, I have drawn together a series of incidents and a collection of people who seemed emblematic, illustrative or symptomatic of the way in which the Cte d Azur developed, as well as being of particular interest to a right-thinking English audience.

I thought it a curious, entertaining and rather salutary story.

Jim Ring, Burnham Overy Staithe

January 2004

Prologue:

The Blue Train

Londons great railway termini are our gates to the glorious and unknown, through which we pass into adventure and sunshine. Or so E. M. Forster thought during the infancy of air travel and in the days when people still took holidays in Britain. In Paddington all Cornwall was latent; from the inclines of Liverpool Street lay fenlands and the Norfolk Broads; Scotland was beyond the pylons of Euston; Wessex behind the poised chaos of Waterloo. But through stolid Victoria lay a land of infinitely greater promise: that of the snow-capped mountains, blue seas and palm trees of the Riviera or, if you had the misfortune to be French, the Cte dAzur.

The novelist Evelyn Waugh found plenty of reasons to make such an escape from London in February 1929. In Labels, his journal of a Mediterranean voyage, he wrote that almost every cause was present which can contribute to human discontent. The government was about to fall, the introduction of talking pictures at the expense of silent cinema had set back twenty years the most vital art form of the twentieth century, and there was not even a good murder case. Above all, though, It was intolerably cold. People shrank, in those days, from the icy contact of a cocktail glass, like the Duchess of Malfi from the dead hand, and crept stiff as automata from their draughty taxis into the nearest tube railway station, where they stood, pressed together for warmth, coughing and sneezing among the evening papers. Waugh, with an enthusiasm for speed and modernity that was soon to abate, flew from Croydon to Paris. Commercial air services were still a novelty. Most travellers to the Riviera took the morning boat train from Victoria, out through the grey suburbs of Battersea and Dulwich, past the hunched winter landscape of Kent to Dover. Then they hazarded their stomachs on the steel grey seas to Calais. It was there that their adventures began, for at the Gare Maritime the Blue Train awaited them.