THE RISE AND DECLINE OF THE REDNECK RIVIERA

THE RISE AND DECLINE OF THE Redneck Riviera

An Insiders History of the Florida-Alabama Coast

HARVEY H. JACKSON III

Publication of this work was made possible, in part, by a generous gift

from the University of Georgia Press Friends Fund.

2012 by the University of Georgia Press

Athens, Georgia 30602

www.ugapress.org

All rights reserved

Maps by David Wasserboehr

Designed by Erin Kirk New

Set in 10.3/14 Chapparal Pro with Mullen Hand display

Manufactured by Thomson-Shore and John P. Pow Company

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and

durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity

of the Council on Library Resources.

Printed in the United States of America

16 15 14 13 12 c 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Jackson, Harvey H.

The rise and decline of the Redneck Riviera : an insiders history of the Florida-Alabama coast/Harvey H. Jackson III.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8203-3400-4 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-8203-3400-6 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Gulf Coast (Fla.)History. 2. Gulf Coast (Ala.)History.

3. Gulf Coast (Fla.)Social life and customs.

4. Gulf Coast (Ala.)Social life and customs.

5. TourismFloridaGulf CoastHistory.

6. TourismAlabama, Gulf CoastHistory.

7. TourismSocial aspectsFloridaGulf Coast.

8. TourismSocial aspectsAlabamaGulf Coast.

I. Title.

F317.W5J34 2011

975.99dc23 2011040110

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

ISBN for this digital edition: 978-0-8203-4378-5

To Suzanne, who brought me back to the beach

Contents

THE RISE AND DECLINE OF THE REDNECK RIVIERA

INTRODUCTION

Alabama Dreaming

IN SEPTEMBER 1944, on the island of Oahu, half a world away from his south Alabama home, a lonely Corporal Jewel Rivers, Jack to his friends, wrote his wife and infant son of the wonders he had seenthe coast, an active volcano, and Honolulu, which he described as quite a town. His journey had been a long one; it would be longer still. This is only a stepping stone to where I am going, he told them. The war with Japan had brought him this far, and it would take him the rest of the way.

While his mind was on what came next, it was also on what would be waiting in the States when the fighting was over. He had seen Waikiki Beach, with its curving stretch of sand dominated by the famous Royal Hawaiian Hotel and Diamond Head. Waikiki was very pretty, but there was somewhere else he would rather be. Ill take the good old Gulf Shores any old day, he wrote. Give me Ala., in the U.S.A., and Ill be satisfied.

Not long after he mailed that letter Corporal Rivers shipped out to New Guinea. Promoted to sergeant, he served as the waist gunner on a B-24 Liberator, flying with the Ninetieth Bomber Group. On November 19, his plane took off to attack a Japanese base on Mindanao Island in the Philippines.

It did not return.

Jack Rivers never saw Gulf Shores again.

But many who served in that war did come back; and in the years that followed, veterans of the front lines and of the home front sought out sand and surf to relax and recover. Along the Alabama and Florida Gulf Coast, from the mouth of Mobile Bay east to St. Andrews Bay at Panama City, residents of the lower South made the beach their own. Children of the Depression and of conflict, more hopeful, indeed optimistic, than they had been in a decade, they drove down on New Dealpaved, military-improved roads in automobiles they bought on easy credit or with cashed-in war bonds. They came on vacations from jobs that they were trained and educated for under the gi Bill. They left behind homes financed through that same program. Few if any cared that their ticket to the middle class had been punched by the federal government.

Along this coast folks from the lower South found a way of life, a culture and context, much like the one they left back homesegregated (where blacks existed at all), small town, provincial, self-centered, and unassuming. Only the landscape was different. Few of the postwar visitors, even the ones who had served in the Mediterranean, would likely have made the connection that was made by a prewar wpa writer who saw in Gulf Shores and Orange Beach reflections of little fishing villages that reminded the visitor of the southern coast of France. Nor is it likely that they would have made the alliterative association that years later Howell Raines, writing for the New York Times, made when he referred to this stretch of the Alabama shoreline as the Redneck Riviera. From there east to Panama City Beach was, as historian Patrick Moore of the University of West Florida described it, a provincial environment committed to tradition, conservative values, and a close tie to regional identity.

Or that is what it has been for as long as I have known it, which is pretty much the length of time covered in this book.

Let me explain.

I grew up in south Alabama, in a little town about a three-hour drive from Gulf Shores. That beach became our beachour Disney World, a friend from childhood called it. Though I was just a tot, I still recall going down with the family in those years after my father returned from defeating Hitler. Later I went back again and again, to deep-sea fish from Orange Beach, to dance at the Hangout, and to sleep in my car or on the sand.

Meanwhile, even as all this was occurring, my attention was being drawn east, over to a spot in Florida, between Destin and Panama City Beach, where ancient dunes had formed a high bluff and where a developer was selling lots. In 1954 my grandmother bought one. In 1956 she built a cottage there, and from then until now Seagrove Beach, Where Nature Did Its Best, has been my other home.

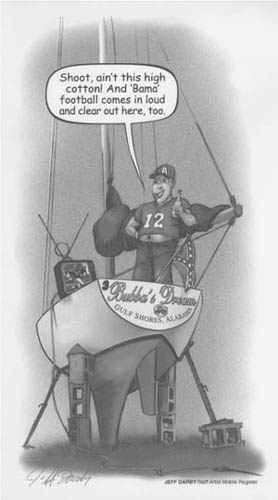

Bubbas Dreamwhat the Redneck Riviera was and is to so many. Cartoon by Jeff Darby; courtesy of the Mobile Press-Register.

It was there that I decided to write this book.

So here it is: my account of how people from the lower South created a coastal playground, a place where they and their families could get away from constraints and restraints of home and job and school and responsibility but without going too farphysically or culturallyfrom where they were. It is the story of how those who were already there, and those who came later, turned fishing villages and bathing beaches into tourist destinations for millions, places where parties were pitched, dreams were dreamed, and fortunes were made and lost. And it is the story of how people keep coming, searching for something new, something old, something upscale, and something sleazy.

Next page