This book made available by the Internet Archive.

TO HIS WIFE

FOREWORD

THE reader for whom it is worth while to write, makes it the habit of his mind to read the Foreword to his book : all through this book it is taken for granted that reader and writer have met upon this first page, and that having met, each understands the other.

The question which I as writer have had to face and answer is this : Why add another to the pile of the world's books ?

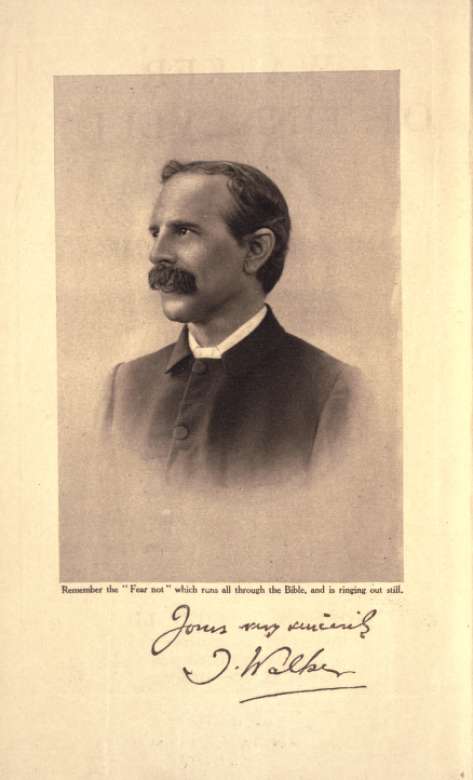

Something had to be written; this was evident before the end of September 1912. If an attempt had not been made by someone authorised, something unauthorised would have been run through the press by affectionate hands and floated out upon the world ; and there was reason to fear that what would have been written might hardly have been in accordance with the memory of one who utterly abominated fulsome speech.

" Too much paint " : it was his summary of the biography of a great and good man, written by a devoted relative. The man himself stood up, when he got the chance, fine in his native grandeur of deed and character ; but the paint spoiled him.

In India we do not paint our teak : we let it show its grain. Poorer stuff is painted : teak asks for no pretence; and this book deals with teak. It does not profess to show a ready-made saint : to do any thing of the sort would be to dishonour the memory of an honourable man. But it has tried to show something of the fashioning of a saint, whose voca

tion called him to live a holy lifenot in the ease of religious seclusion, nor in the midst of those rare heroic circumstances which emphasise the glory side of existence, but along the dusty levels of com monplace ways. Journal, letter, and reminiscence show the grain of the wood. There has been no painting, no pretence.

A second answer to that question was found in the wish of fellow-missionaries. This is not a usual wish, for a missionary's severest critics are his fellows; he is one of themselves, they consider him with discrimination, quite impartially, and they see no halo, only an ordinary exterior usually much the worse for wear.

" Greatheart is dead they say;

But the light shall burn the brighter,

And the night shall be the lighter

For his going ;

And a rich, rich harvest for his sowing : '

these lines from John Oxenham express what I think about him," so a Tinnevelly missionary wrote between college classes early in 1913. " If the book is a quarter the inspiration his life was, it will be well worth doing," wrote another. When missionaries write thus about a fellow-missionary, he must be worth knowing.

But the word which compelled, and gave assur ance of help for the difficult work, was briefly this : ' Write the things which thou hast seen."

And yet how very little after all can be written. We call a book a " Life " which deals with the material substance of doings and sayings. A fragment would be a truer name, for at most it can be little more ; the spiritual, the innermost, remains a secret still. Something of " Walker of Tinnevelly " may be shown in the pages of this book, but he himself will be else where. No pen may intrude into the private place

where the real man was, and where the springs rose which fed the river of being.

That river, so far as may be, has been traced from its source to the splendid moment when it suddenly found itself received into the ocean. In other words, the book is a frank return to the older method of biography. There is no attempt made in these pages to do the reader's thinking for him. He is left to do it for himself. The story of the boy, student, curate, missionary, is told straight on, for the most part, year in and year out, with as little as possible of the biographer and as much as possible of the man him self. The newer writing, with its clear grouping of subjects, is undoubtedly more popular than the older, which has only one thought, to leave the reader with his man and let him get to know him in his own way but the man of this book liked the old method better: for as to dates, he liked to know where he was at any given point of a book ; and as to subject-matter, he liked to do his own grouping and to make his own pictures. Perhaps there remain among us some who feel as he did ; if so, the book will find out its own. In any case, it seemed impossible to the writer to do otherwise than what has been done for Walker of Tinnevelly.

As to data for facts: A journal kept from 1st December 1885 to 19th August 1912 (with two well-defined breaks) has been a guide from Chapter III to the end, and letters lent by his family and friends contribute to the truth of the book. Extracts from such sources are often condensed ; where a word of explanation seemed required, such is put in square brackets ; and in some few cases, where no good purpose would be served by tracking foxea to their holes, or worthy persons to their home addresses, initials have been changed, in obedience to an instinct which urged that he would wish it so to be.

Naturally there has been cause for reserve; for many of the events with which the records deal are too recent or too intimate for telling. And those who knew him best will miss something of the clash of arms, in the story of this man who was somehow perpetually being forced into conflict; for but little of that conflict is described. And for this reason: most of the various rocks of diverse opinion round which at different periods of his life his thought revolved in strong current, are for the time being under water: the tide of thought has flowed over them: they are not at the present moment challenging the expression of every man's opinion. To insist therefore upon the reader's concerning himself with them whether he will or no, seemed to the writer likely to frustrate the intention of this book, the spiritual intention. And it seemed alsoto revert to the martial figurethat even if it were in each case possible to set forth the casus belli, the result might be to raise a dust of words which would perhaps obscure that which those who read will most desire to seethe personality of the man who fought, his earnestness, his integrity, his greatly increasing happiness, his faith, simple as a child's but valiant as life. These are the things that last when other things are forgotten.

And another thought has been with me too. Is it not true that in this clamorous world, in the midst of the weariness and strife, there are some who are glad to turn sometimes into byways of quiet ness, glad to meet in those private ways men from whom it may be they must differ in public, glad to get to know them underneath and above all difference, in that mystic communion of spirit which will surely be one of the joys of heaven ?

This, then, has been the guidance so far as the writer understood it. It would be a poor end to the

writing if even one reader being drawn in thought into controversy, and touched unaware by the bitterness of it, should lose the sweetness of a new friendship begun here to be continued There.