For

Fred Blackburn

Vaughn Hadenfeldt

Matt Hale

Greg Child

Stalwart and savvy companions on many of my best adventures in the Southwest.

Contents

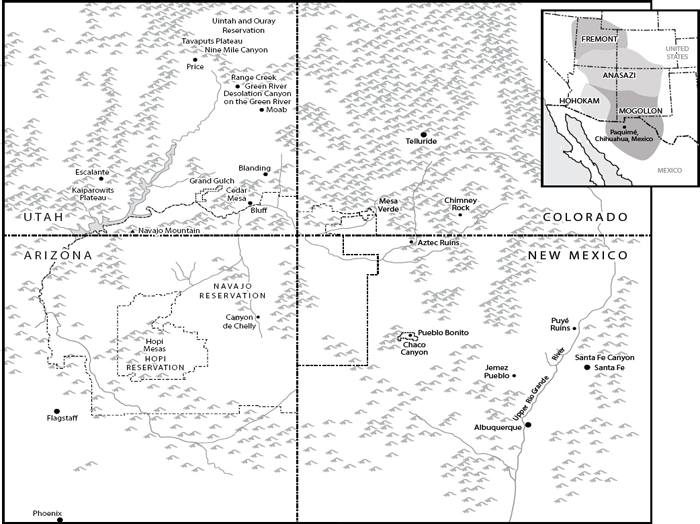

F or more than an hour, the three of us climbed the steep, trailless canyon wall, pushing through scratchy thickets of scrub oak and across exposed sandstone slabs. We had long since lost sight of the curious speck in the middle of the overhanging cliff that we had scoped with binoculars from the dirt road beside Range Creek a thousand feet below us. That speck had been pointed out to us by Waldo Wilcox, the seventy-five-year-old rancher who had spent his whole adult life on the twelve-mile-long family spread in Range Creek, a tributary of the Green River in east-central Utah that carves a majestic chasm through the lofty Tavaputs Plateau.

After years of exploring the backcountry of the Southwest in search of prehistoric ruins and rock art, Greg Child and I were used to this sort of scrambling, so we chose the approach route, keeping the location of the cliff toward which we were headed tucked in the backs of our minds. For archaeologist Renee Barlow, such an adventure was relatively new, so she went along with our pathfinding with only a modicum of second-guessing.

It was a warm day in May 2005. Hiking in shorts and T-shirts, we were soaked in sweat.

Fifty-four years earlier, in 1951, only months after Waldos parents had bought the ranch, his father Ray (known as Budge), his brother Don, and twenty-one-year-old Waldo had stood on the same dirt road and argued about that speck in the distant cliff.

Theres somethin there, right in the middle of it, Waldo had said. Some Indian thing.

Nah, countered Don, five years older. Its natural. Just rocks. Budge agreed: Yep. Rocks or ledges or somethin.

The next year, in 1952, the army drafted Waldo and shipped him to Japan. During his two-year stint in the forces, he used field glasses for the first time. The tantalizing Indian thing on the high cliff was often on his mind, so he bought a cheap pair of Japanese binoculars and mailed them home. Back in Range Creek in 1954, he trained the instrument on the distant apparition.

They wasnt that good of field glasses, Waldo told me in 2005, but I could see everything that was there. Sure enough, it was a big old granary halfway up this sheer cliff.

One day Waldo tackled the arduous scramble to the foot of the cliff, following much the same route the three of us would pursue half a century later. Arriving at the base of the precipice, he was stunned at what lay before him. He could see the big old granary well, sixty-five feet above him, but could not imagine how to get to it. After a good long look at this prodigy of prehistoric architecture, he descended the thousand feet to the valley. Over the years thereafter, he kept his silence about what he had found. Budge and Don, less curious than Waldo about Indian things, never bothered to undertake the tricky bushwhack up the canyon slope to check out the granary for themselves.

After the Wilcoxes had bought the Range Creek ranch in 1951, they built sturdy gates on the old dirt road at either end of their property to keep out trespassers. Waldos parents and his brother Don soon moved on to other ranches in the Tavaputs, while Waldo, his wife, Julie, and eventually their four kids stayed on in Range Creek. For schooling, from September to May, the kids and Julie moved into the familys snug house in Green River, thirty-five miles away, while Waldo lingered on with his cows, the lonely lord of his outback estate.

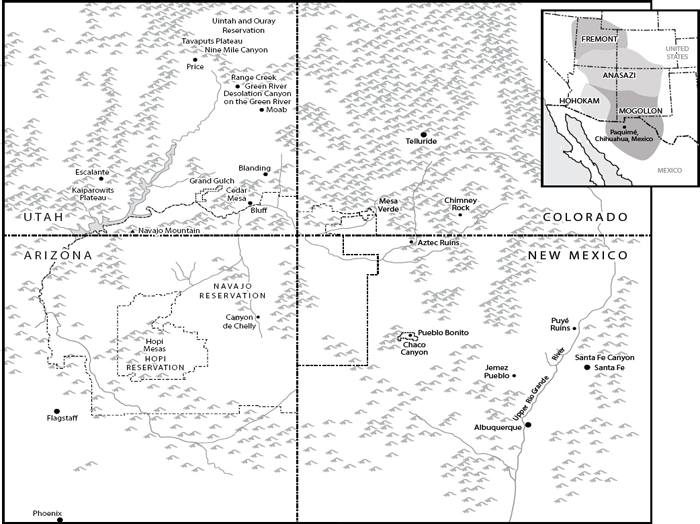

A thousand years and more ago, Range Creek had teemed with part-time hunter-gatherers who also raised corn, beans, and squash. These ancients are known to science as the Fremont people, northern neighbors of the Anasazi, or Ancestral Puebloans. Still poorly understoodwe have no idea, for instance, what became of the Fremont after they vanished entirely from the archaeological record around A.D. 1500the Fremont pose one prehistoric conundrum after another.

For fifty years, everywhere Waldo wandered in Range Creek, chasing stray cows or hunting bears and mountain lions, he stumbled upon Indian stuffpotsherds, chert flakes left by arrowhead makers, manos and metates for grinding corn, rings of stones outlining the shallow pithouses in which the Fremont lived, dizzy granaries on cliff ledges where they stored their precious grain, and even the graves of the long-dead. Unlike so many ranchers in the West, for whom collecting and hoarding artifacts is a time-honored tradition, Waldo left virtually everything he found in place and undisturbed. Its the way I was brought up, Waldo said to me in 2005. Mom and Dad always told me that just cause we owned the land didnt mean the Indian stuff belonged to us. They wouldnt go the cemetery and dig folks up just for the gold in their teeth.

In 2001, with a heavy heart, Waldo succumbed at last to the limitations of old age and sold his ranch to the Trust for Public Lands and the state of Utah. Eventually the property landed under the aegis of the states Division of Wildlife Resources (DWR), some of whose functionaries cherished visions of turning Range Creek into a prime bighorn sheep hunting reserve, with a blue-ribbon trout stream running through its hearteven if that might have required cutting down all the pion and juniper trees in the canyon to improve the habitat. In the meantime, however, archaeologists got a look at Range Creek. Uniformly astounded, the experts agreed that Range Creek had the potential to tell us more about the Fremont than had the combined efforts of the seventy previous years of research since the culture had been identified.

Keeping Range Creek a secret for three years, an archaeology team out of the Utah Museum of Natural History (UMNH) started to make a systematic survey of the canyons glories. But a local newspaper leaked the story in the summer of 2004, touching off a wildfire of national media coverageand a furor among Native Americans from New Mexico to Nevada, who were royally pissed off to have been kept in the dark about a hidden valley that, some of them insisted, might have been part of their own ancestral heartland.

Mesmerized by the news about Range Creek, I got magazine assignments from National Geographic and National Geographic Adventure. Afire with a passion to explore this unknown wilderness, I made a phone call to Greg Child that put the match to his kindred ambitions. In Price, we met Renee Barlow, co-leader of the UMNH team, who at once welcomed us to join her on her prowls through Range Creek. As climbers, Greg and I could get Renee to places none of the UMNH team could reach on their own. On our first visit to the remote valley, Greg and I recognized that while the creek bottom abounded in sites and artifacts, all the most spectacular ruins lay in high eyries that would be extremely hard to get to. Oddly enough, Renee was the only member of the team who shared Gregs and my ambition to explore those inaccessible sites.

None of them exerted a more powerful allure than the speck in the overhanging cliff a thousand feet up the west side of the canyon that Waldo had spotted in 1951 and scrambled up to three years later. In the fifty-one years since his jaunt, no one else had visited the big old granary Waldo had discovered.

Next page