Sites of Other Cultural Traditions

T he chapters in this guidebook are organized according to the ancient cultures (archaeological categories) to which the sites belongArchaic, Fremont, Hohokam, and so forth. However, there exist some stand-alone sites; that is, in a particular cultural category, they are the only examples that are open to the public. Keyhole Sink is Cohonina, for example, and Lynx Creek is in the Prescott Tradition. This final chapter of the book includes five such sections.

THE DINETAH

To enter the Dinetah, follow US 64 east from Bloomfield to Blanco, New Mexico. After crossing the San Juan River, turn right on County 4450. From there, you will need the Bureau of Land Management map/brochure Defensive Sites of Dinetah, which shows back roads and locations of eight archaeological sites. Another approach is to hire a professional guide. Information: (505) 564-7600; (800) 842-3127; www.blm.gov/nm/st/en/prog/recreation/farmington/dinetah_pueblitos.html.

The Dinetah is an extensive canyon-cut area northeast of Bloomfield, which Navajos regard as their ancestral homeland. Archaeological research confirms that many sites around the Largo and Gobernador river drainages date back to early Navajo presence in the Southwest.

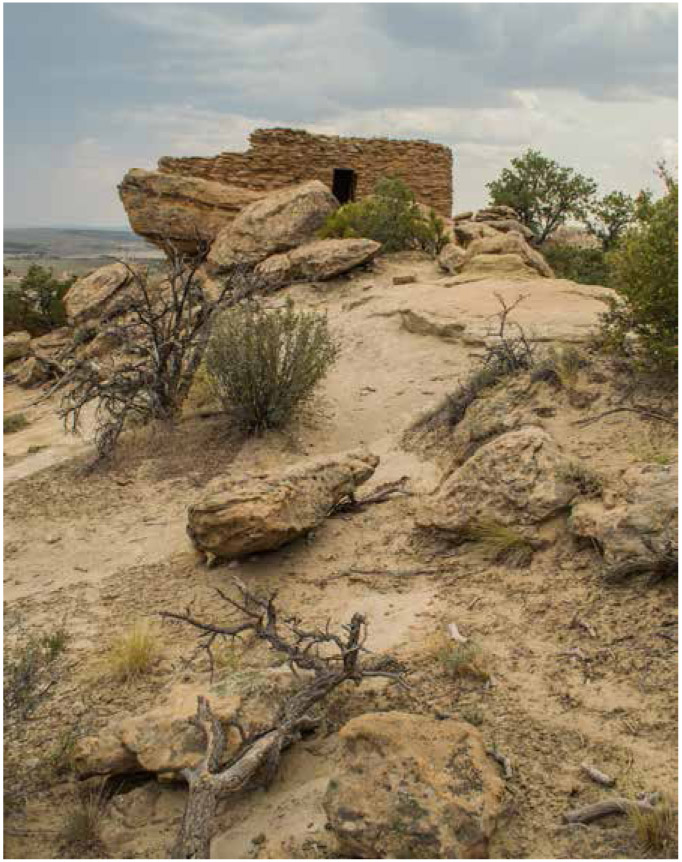

The three types of archaeological sites that you will find of particular historical interest in the Dinetah are pueblitos, forked-pole hogans, and rock-art panels. Dinetah archaeological researcher Ronald H. Towner has described the first as small stone structures built on boulders, mesa rims, and other prominent topographic features. Although most consist of only four or five rooms, some are smaller and others as large as forty rooms. Often, the remains of early-style hogans are found near the pueblitos. These dwellings, which resemble tepees in general form, were made by first leaning together three cedar poles in a tripod structure. More poles were laid against these to form a conical framework that was covered by bark and earth. The Dinetah also is noted for its stunning petroglyph and pictograph panels, some of which are easily accessible and well preserved. They, too, reflect early Navajo, as well as Pueblo, occupation of the region.

The Navajos, or Din, are of Athapaskan origin and related to Indians of northern Canada and to the Apache. Anthropologists think their southward migration began around 1000 CE and that they arrived in the Dinetah, and probably some other areas, sometime after 1450. Because of sparse archaeological data, science-based reconstructions of early Navajo history are uncertain and have been much debated. Navajo origin stories, on the other hand, tell of a long-ago emergence into this world from a subterranean domain and contact with supernatural beings.

Navajo rock art panel in Crow Canyon in the Dinetah. Dating to the eighteenth century, it depicts a corn plant, a yei figure, and various designs including concentric circles.

Dendrochronology (tree-ring dating) shows that construction of most pueblitos took place from the early to mid-1700s. Their locations and design suggest their Navajo builders were much concerned about defense. Ute and Comanche raiding parties posed an ongoing danger to the Dinetah settlements; in addition, they were under pressure from the expanding Spanish colony in the Rio Grande Valley. Little hard evidence of actual violence and conflict, however, has been found at the few sites that archaeologists have excavated.

A pueblito in the Largo-Gobernador region.

After the Pueblo Revolt in 1680 and subsequent conflicts with Spanish military forces between 1692 and 1696, some Pueblo refugees came to the Dinetah region. One pueblito in particular, Tapacito Ruin, built in 1694, appears to be Puebloan, rather than Navajo. Pueblo Indians had other interactions with Navajos through both trade and warfare, and some Navajo clans originated through these contacts.

Since the Dinetah region had limited land suitable for farming and grazing, it eventually could not support a growing Navajo population. Consequently, in the mid-1700s, many Navajos moved to more favorable areas to the south and west. Conflicts with the Utes and Comanches provided addition motivation to move away. Today, three hundred years later, their stone houses, many precariously situated but well built, remain for us to see.

A day exploring the Dinetah can be very rewarding. You can expect to see rooms built of stone, some perched on boulders or along the edge of cliffs. The views from them over the landscape are spectacular. You will gain a sense of how threatened the Navajo occupants of these habitations must have been three hundred years ago. The rock-art panels in Crow Canyon are truly impressive as well and provide insights into Navajo ceremonialism and religious beliefs.

To make the most of visiting this area, a guided tour can be arranged through Salmon Ruins (p. 129) or the Bureau of Land Management. You should be prepared to drive miles on unpaved roads, which can be dusty or slick depending on weather conditions. A high-clearance, four-wheel-drive vehicle is recommended. On weekdays, expect to encounter truck traffic from the areas active oil and gas industry.

Suggested Reading:Defending the Dinetah, by Ronald H. Towner, University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City, 2003.

AGUA FRIA NATIONAL MONUMENT

Entrances to Agua Fria National Monument are located along Interstate 17, 40 miles north of central Phoenix, Arizona. The Badger Springs (256), Bloody Basin (259), and Cordes Junction exits lead into the monument. A short distance from the exits are informational kiosks with large-scale maps. Information: (623) 580-5500; www.blm.gov/az/st/en/prog/blm_special_areas/natmon/afria.html.

Agua Fria was proclaimed a national monument in 2000 in large part to protect its many archaeological sites: pueblo ruins, rock-art panels, agricultural terraces, and some linear features colloquially called racetracks. The Bureau of Land Management, which manages the 70,000-acre preserve adjacent to Tonto National Forest (which contains similar sites), has made improvements to facilitate access to four sites: Pueblo La Plata, Badger Springs, the 1891 School House, and the Tesky Homestead. The last two historic sites are accessed through the Cordes Junction entrance.

Pueblo La Plata in Agua Fria National Monument.

Perry Mesa, a 75-square-mile expanse of grassland in the eastern portion of the monument, contains a wealth of archaeological resources. Investigators have determined that between around 1250 and 1425, the people who lived here had their own particular cultural identity, which is recognizably distinct from that of the nearby Sinagua, Hohokam, and Salado. They call this identity the Perry Mesa Tradition. The mesa and ancestral Native American group were named for a homesteader, William H. Perry.