My thanks for kindnesses contributing to the completion of this book: Larry Benson, Wesley Bernardini, Sally Cole, Janice and Joe Day, Severin Fowles, Robert Kelly, Timothy Kohler, Jay Miller, James Collins Moore, John Pohl, David Roberts, Joe Traugott, and Richard Wilshusen. Ruth and Ken Wright and Sean Rice generously supported the books production. To all: Thanks!

Much of was written at the School for Advanced Research in Santa Fe; most of the rest was written at the University of Colorado, Boulder. For developmental editing, my thanks to Lynn Baca (MEREA Consulting). And thanks to the excellent people of the University of Utah Press: Reba Rauch and Patrick Hadley; and copyeditor Virginia Hoffman (Last Word Editorial Services) and Ina Gravitz Indexing Services. All of the above are innocent of my transgressions, real or imaginary.

Preface

We poets in our youth begin in gladness;

But in the end, despondency and sadness.

with apologies to Agatha Christie (A-Sitting on a Site),

who apologized to Lewis Carroll (Aged Aged Man),

who apologized to William Wordsworth (Leech Gatherer)

Plan of the Last Book

If you are a Southwestern archaeologist, I wrote this book for you, but you may not enjoy reading it. Im a Southwestern archaeologist, and I did not enjoy writing it. Its basic premise is also its dismal conclusion: Its almost impossible for American Anthropological Archaeology to do justice to the ancient Southwestto get it rightbecause of biases we inherited from our intellectual forefathers/foremothers. And because archaeology is deeply entangled in Southwestern popular culture and seriously estranged from Southwestern Indigenous peoples. All these make it hard to do good, accurate archaeology. Almost impossible.

But of course that depends on your definition of archaeology. Now more than ever, archaeology appears to be whatever archaeologists want to do, whatever makes archaeologists happy (attrib. to Albert Spaulding). My archaeology is history and science, using those terms in their narrow European Enlightenment meanings. More than that: I insist that archaeology must be history first, before it can be science. Unless we get the history right (more or less), we probably will do silly science: Ask the wrong questions and get irrelevant answers.

But history and science operate by very different rules: History makes arguments, science tests theories. A methodological conundrum: We think we know how to do science, but very few of us have thought about how to do narrative historyhistoriography for prehistory! Hereafter I will refer to the narrative history of ancient times with this awkward, hyphenated term: pre-history. (Hereafter, sans hyphen prehistory = ancient times.)

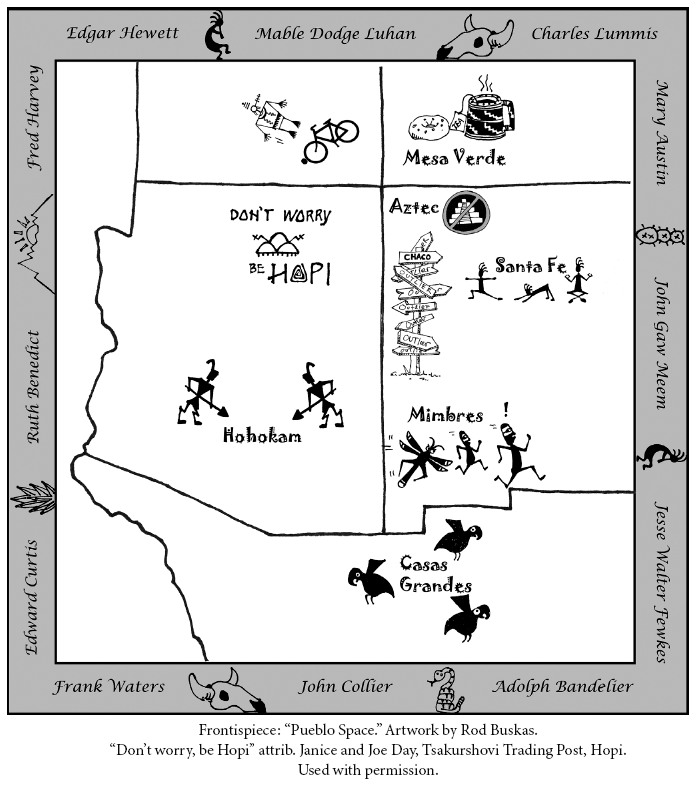

The focus of this book is Southwestern archaeology, and its central case study is Chaco. The specific argument is that Southwestern archaeology has been getting Chaco wrong for over a century because of something I will call Pueblo Space: Everything in the past must be Pueblo, Pueblo-ish, or leading logically to modern Pueblos. This biasand it is a biascomes from a variety of causes explored in , I present Chaco freed (I hope) from Pueblo Space, a new pre-history. To preview: Chaco was a small, secondary state with nobles and commoners, similar in structure to a particular, fairly common Mesoamerican model of its time; it had a small capital city at Chaco Canyon and a large region or hinterland encompassing several tens of thousands of people. Theres nothing like that in Pueblo Space.

If we escape Pueblo Space, the science we can do with Southwestern data is rather different than what we currently do. I offer a few ideas using my version of Chaco for science in suggests possible beginnings for pre-historiography: Theories and methods that might (or might not) be useful for producing narrative history for ancient times.

Theres a narrative arc or logic both to the book and to individual chapters, but it's messy and sprawling. As Albert Einstein reportedly said, If you are out to describe the truth, leave elegance to the tailor. Im sure Im far short of truth, but to get anywhere at all, I had to abandon all hope of elegance.

What Do You Want Us to Do?

A question: Not Yalis to Dr. Diamond; nor the Bridge-keepers Three to Arthurs knights; nor Dirty Harrys to the luckless punk. The question came from a graduate student at Arizona State University, after Id given a colloquium arguing that Anthropology was not a good intellectual home for ancient North America. The audience consisted of the ASU Anthropology faculty and, behind them, a score of graduate students. A tough crowd: Murderers Row up front and, back in the cheap seats, a seething pack of critically thinking students. And all of em (most of em) smarter than me. But after I told them thatoopsthey had taken jobs in the wrong discipline, they treated me with restraint and generosity. Many good questions andfrom the back of the hallthe one that titles this section: What do you want us to do? Good question! I was taken aback. I hadnt thought that far; Id recognized a problem but I hadnt figured out howto solve it. My response at the time was tactical: Nothing, until you get tenure! (A growl of agreement from the ASU faculty.)

This book answers that question. What do I want young Southwesternists to do? Reinvent North American prehistory, somewhere outside or beyond or parallel to American Anthropology. Late in life I realized what my elders knew: That the archaeology of North America landed in Anthropology by accident, or by colonial designwhich is worse ()? Boshtell that to the Classics Department.

The archaeology of ancient North America sits firmly in the bosom of Anthropology (with rare appearances in Art History). And of course that wont change. But its really interesting and useful to think: What if, back in the late nineteenth century, archaeology had been assigned to Historythe most obvious alternativerather than Anthropology?