I am deeply indebted to my mother, Louise McLanahan Noble, for saving all the letters I wrote home from Vietnam and sending them to me before she died. Colonel Kumar of the Indian army, with whom I became friends in Saigon, gave me a broader perspective of the war in Vietnam. The Jarai and Bahnar people of Vietnams Central Highlands taught me, by their very presence, about the dignity of all human beings, whatever their social and cultural background or level of economic development. My sister Alexandra Heller read developing versions of the manuscript and assured me of its value and that a publisher surely would be interested. My friend Krista Elrick helped me repeatedly with digital and computer complexities. Barbara Feller-Roth assisted me editorially, from missing commas to narrative organization and the blending of letter excerpts with memoir. Ruth Meria Noble did the proofreading.

Preface

While I was in college in the late 1950s, my interest in American politics and international affairs was near invisible. With no radio or television, it took events such as Sputnik , the Berlin Crisis, and the Kennedy-Nixon campaign to get me to a newsstand. In those years, to be uninvolved in politics was not unusual on college campuses; of course, with the draft and the military buildup in South Vietnam a few years later, this dramatically changed.

One personal political incident, however, sticks in my memory. It was early one morning in the fall of 1957. I was hunched over a textbook in a reading room, cramming for an upcoming test, when I heard a commotion near the rooms entrance. Clearly, some thoughtless people were ignoring the Quiet please! sign on the door. I was trying to focus on my work when I suddenly heard a commandingthough not unfriendly and not unfamiliarvoice behind me say, Wake up there, young man! I swiveled around to find former President Harry S Truman gazing down on me. He smiled mirthfullya gotcha moment!then turned and strode out of the room to continue his early morning constitutional, Secret Service agents scurrying to keep up. Truman, I learned, was on campus as a visiting fellow. Did my brief encounter with the former leader of the free world spur me to attend one of his seminars, or join the Political Union? No. But later, my apathy to politics vanished. Vietnam did that.

In April 1962, only nine months after graduating from college, I was in the army stationed at Fort Holabird, Maryland, and received orders to report to a classified counterintelligence unit in Saigon. So unprepared was I for such an assignment that my first move was to the fort library to find out where Vietnam was.

Not surprisingly, the twelve months I spent in Saigon and Pleiku were very intense and personally formative; even after the passage of years, those experiences remained strong and vivid in my mind. Memorable, too, was the decade that followed my military service, when Americas cities and campuses erupted in controversy over Vietnam, and a Stop-the-War movement was born, gained strength, and, finally, helped end the war.

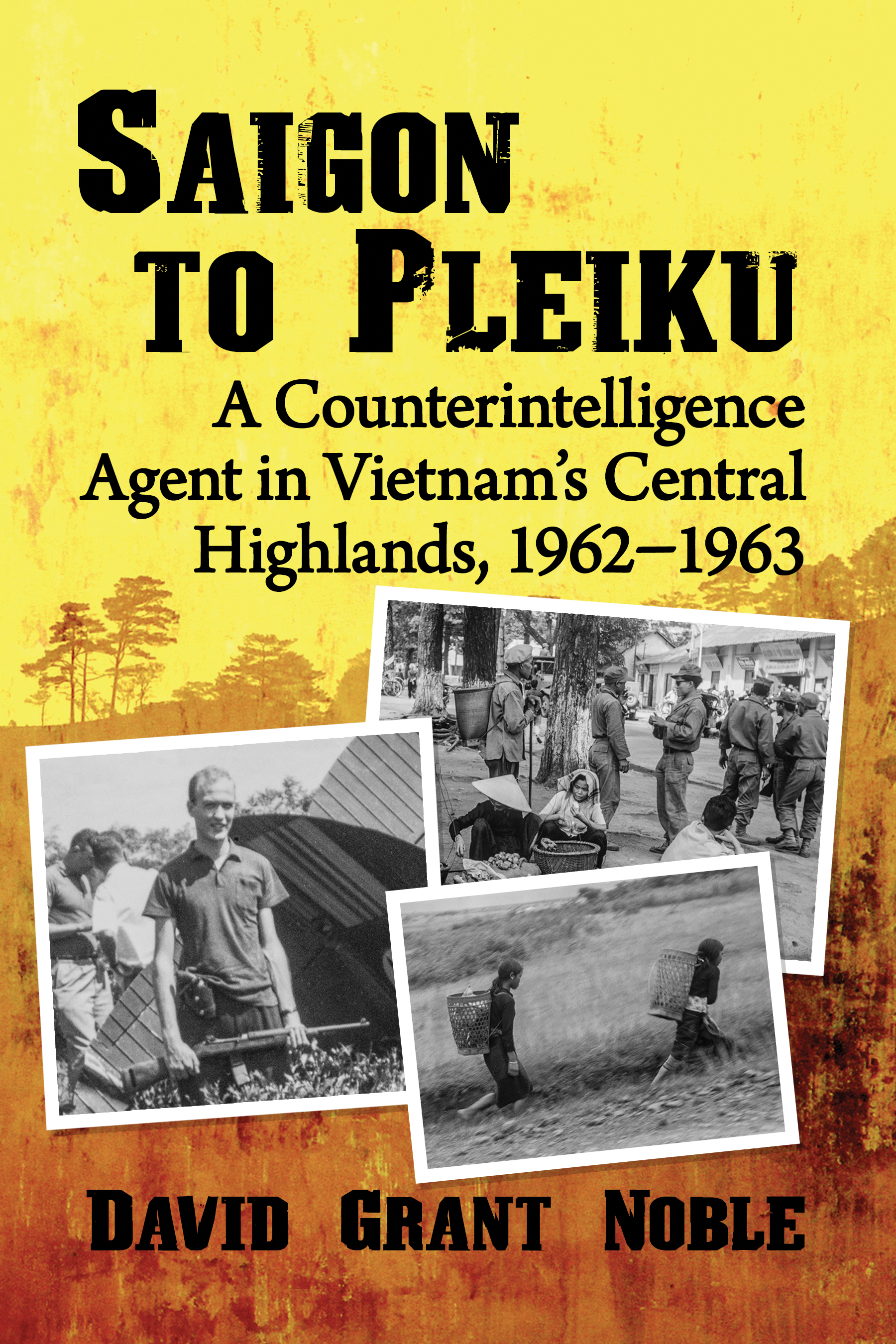

In Pleiku, where I spent most of my tour, I was a young, greenhorn special agent trying to collect intelligence that would help America support what we were led to believe was a struggling democracy fighting an aggressive communist dictatorship. Six-foot-two and blond, I was supposed to be operating undercover. At the time, I thought what I was doing was important; of course, history proved that wrong. My reports from the Central Highlands, a territory inhabited by more than thirty indigenous tribes known collectively as Montagnards, were, indeed, informative to headquarters in Saigon; but they changed nothing in the long run. On the other hand, what I did and experienced in Vietnam had importance at another level: I began to learn about the world, and where I stood in relation to American foreign policy, and, of course, the real nature of the Vietnam War.

It was my luck that I served very early in the warbefore the Bay of Tonkin, and before so many young Americans and many more Vietnamese perished or were maimed. My time there in 1962 and 1963 is a period about which the American public generally knows little. Army intelligence-gathering activities in the Central Highlands are even less well-known. They were secret then and remain obscure today. More than half a century later, in one army archive after another, I have tried to gain access to the Intelligence reports I wrote from Pleiku, and, in every case, ran into a stone wall: no trace or no interest, it seems.

The following pages contain only my storywhat I did and what happened to me . They do not pretend to be the story, whatever that may be. What Ive written includes both memoir and excerpts from letters I wrote home while I was in Vietnam. These my mother savedabout sixty of themand sent to me before she died in 2002. The following narrative casts some light on a thin slice of military history, but it is also a coming-of-age story about a naive, inexperienced, youth who, under demanding circumstances, learned something about himself and about life. It follows his journey from a believer in his countrys policies to a dissenter.

I wrote this story not only because I needed to, but also because every aspect, however small, of this unfortunate war should be brought to light. I was twenty-two when I went to Vietnam. Now I am eighty-one. Like many octogenarians, I spend no little time in reflection; but the words in the following pages are not the nostalgic (or guilty) memories of an old man. I drafted this narrative when the experiences were still relatively fresh and vivid. As to the letters, they were written almost in real time, usually within twenty-four or forty-eight hours of when the events occurred. So, too, for my accounts included in Part III, of the anti-war rallies and marches I joined later in the sixties. To protect their and their families privacy, I have changed some names; they are Gordon Gallagher, Mike Smith, Robert Kuhn, Kumar, Nelson, Don, and Jake. To keep their authenticity, the excerpts from my letters are reproduced as originally written, without editing. As to the photographs, especially of the Montagnards, I hope they convey, with some immediacy, a feeling for the dignity and beauty of these indigenous people, who were caught in the middle of terrible events that were far beyond their control, and who suffered much.