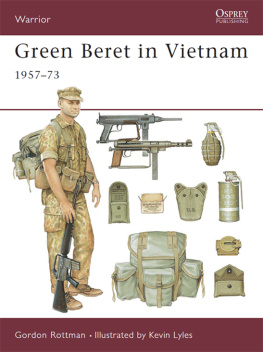

Warrior 28

Green Beret in Vietnam

195773

Gordon L Rottmann Illustrated by Kevin Lyles

CONTENTS

GREEN BERET IN VIETNAM 195773

SPECIAL FORCES OVERVIEW

When Special Forces (SF) soldiers reflect upon their service with the US Armys complex and controversial involvement in Vietnam, they rarely relate similar experiences. Such men were asked to fulfil a wide variety of operations and missions camp strike forces, mobile strike forces, mobile guerrilla forces, special reconnaissance projects, training missions, and headquarters duty and each provided vastly different circumstances for SF soldiers.

The span of time was an equally important factor that affected the experiences of SF soldiers. Special Forces involvement in Vietnam began in 1957 and ended in 1973. Even a difference of one year would result in contrasting perspectives, as the war was fought in a constantly changing environment. Terrain and weather conditions were similarly important. Vietnam offered varied geographic environments, ranging from chilly, forested mountains in the north, vast open plains in the central highlands, triple-canopy inland jungles, dense coastal swamps, and the inundated flood plains of the Mekong Delta. It was often said that Vietnam has three seasons; wet, dry, and dusty, which recur at approximately hourly intervals.

The effectiveness of an SF detachment was often determined by the personality of its members. While a certain degree of guidance was provided in the operation of A-camps and other SF activities, there was no official doctrine guiding day-to-day operations. In Vietnam, there was only lore, and what was found to work best in a given situation. Expedients, substitutes, ingenious makeshift efforts, and resourcefulness were a matter of course. There were inevitably similarities between camps, but differences in routine were often vast.

This book will focus on the experiences of SF troops involved with camp strike forces. The more glamorous Special Forces missions, reconnaissance projects, and MIKE Forces for example, are more publicized in popular literature, but it was the A-camps that epitomized the heart and soul of Special Forces in Vietnam.

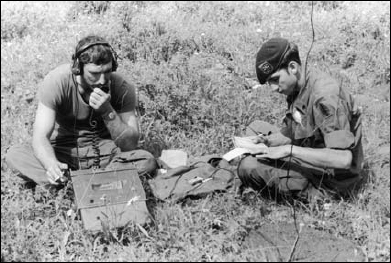

All SF troopers were required to specialize in a specific skill. Here communications NCOs practise encrypting and transmitting messages.

The camps, which were usually staffed by fewer than a dozen Americans in some of the most remote and inhospitable regions of Vietnam, were bases for indigenous, irregular counterinsurgency forces. They struggled to stifle the flow of enemy forces and supplies from across the borders, and they secured isolated ethnic minority villages to prevent their exploitation by ruthless enemy forces. The A-camps experienced counterinsurgency at grassroots level and were involved in all aspects of counterguerrilla warfare; training, advising, and fighting with indigenous troops. To this end, they were also involved in the interrelated field of psychological operations (influencing the opinions, attitudes, and behavior of enemy forces, indigenous populations, friendly and military), civic action (improving local economic and social conditions), and intelligence collection (through reconnaissance, informers, and low-level agent nets in the camps area).

SF training focused on the practical as well as the technical. Here a group of engineers attempt to construct a bridge with only hand tools. They would later destroy it as part of their demolitions training.

Away from the battlefield, Special Forces gave medical, educational, agricultural, and housing construction assistance to the troops families and local villagers. MEDCAP (MEDical/Civic Action Program) visits to local villages were routinely made.

Image and reality

The popular image of Special Forces, which has unfortunately been influenced by the inane vision of John Rambo and other equally far-fetched motion picture characters, is far from reality. Such flamboyant, risk-taking characters would not have survived a single contact. The image of SF during the Vietnam era was also influenced by Robin Moores fictionalization of some more glamorous exploits, The Green Berets (1964); John Waynes motion picture of the same title (1968), and Staff Sergeant Berry Saddlers popular song, The Ballad of the Green Berets (1966). Rumors, assumptions, war stories, and the efforts of the John F. Kennedy Center for Special Warfare to promote its capabilities in countering communist-sponsored peoples wars were just as much responsible for the popular image of Special Forces.

Soldiers invariably reflect the society that spawned them, and Special Forces soldiers demonstrated the highest values of American society. Most SF troopers were conservative by nature, but virtually apolitical.

SF students prepare to launch a 12ft semi-rigid assault boat. A 40hp outboard motor will be mounted on the transom. This type of training was often incorporated into hands-on exercises in the field rather than through formal instruction.

A typical SF trooper, although most would resent such a generalization, was of higher than average intelligence (determined by extensive testing), no more physically fit than other paratroopers, generally moderate in temperament, and able to maintain a sense of humor (a critical requirement in Vietnam), which often leaned toward the dark side. There were heavy drinkers and teetotallers, hardcore lifers, rednecks, cowboys, intellectuals, surfers, and motorcycle-gangers, to name a few. None were fanatical or ultra-right wing as often envisioned by a paranoid Hollywood.

A specialist 4 of the 5th SFGA headquarters endures the SF-run jump school at Dong Ba Thin where MIKE Force troops undertook jump school. The school was considerably tougher than Ft Benning, Georgia.

There was a tendency to cut-up during training, and pranks were commonly inflicted on non-SF units and themselves without prejudice. However, SF was not a group of wild, rebellious misfits as portrayed in many motion pictures, although some senior commanders might argue otherwise. Regardless of personal attitudes, they were professional in appearance and actions. They were distinct individualists from a broad range of backgrounds with several things in common. Most were looking for something different and challenging, they wanted to prove themselves, and they were idealistic in a mildly patriotic, and at that time, unpopular way. Admittedly, most troopers distrusted overbearing, power-hungry, overly career-oriented officers.

Though it was not the goal of the selection process, troopers tended to have common attributes. Most were somewhat rebellious and independent, but still capable of working as members of a team; plus they tended to support the underdog, an invaluable attribute when it came to working with indigenous troops. They were all strongly anti-communist, though not because of indoctrination or political nurturing. All were triple volunteers, for the Army, Airborne, and Special Forces. They had to be at least 20 years old, have the same General Technical score (a form of IQ score) as required of officers, and have no police record. However, a surprising number had been in minor trouble with the law. A comparatively clean record was needed to obtain the required security clearance.