In Search of the Old Ones

EXPLORING THE ANASAZI WORLD OF THE SOUTHWEST

DAVID ROBERTS

SIMON & SCHUSTER PAPERBACKS

NEW YORK LONDON TORONTO SYDNEY

EXPLORING THE ANASAZI

WORLD OF THE SOUTHWEST

DAVID ROBERTS

ALSO BY DAVID ROBERTS

ONCE THEY MOVED LIKE THE WIND:

COCHISE, GERONIMO, AND THE APACHE WARS

MOUNT MCKINLEY: THE CONQUEST OF DENALI

(with Bradford Washburn)

ICELAND: LAND OF THE SAGAS

(with Jon Krakauer)

JEAN STAFFORD: A BIOGRAPHY

MOMENTS OF DOUBT

GREAT EXPLORATION HOAXES

DEBORAH: A WILDERNESS NARRATIVE

THE MOUNTAIN OF MY FEAR

In Search of

the Old Ones

SIMON & SCHUSTER PAPERBACKS

NEW YORK LONDON TORONTO SYDNEY

SIMON & SCHUSTER PAPERBACKS

ROCKEFELLER CENTER

1230 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS

NEW YORK, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

COPYRIGHT 1996 BY DAVID ROBERTS

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED,

INCLUDING THE RIGHT OF REPRODUCTION

IN WHOLE OR IN PART IN ANY FORM.

SIMON & SCHUSTER PAPERBACKS AND COLOPHON ARE

REGISTERED TRADEMARKS OF SIMON & SCHUSTER, INC.

FOR INFORMATION ABOUT SPECIAL DISCOUNTS FOR

BULK PURCHASES, PLEASE CONTACT SIMON &

SCHUSTER SPECIAL SALES AT 1-800-456-6798 OR

BUSINESS@SIMONANDSCHUSTER.COM

DESIGNED BY KAROLINA HARRIS

MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS HAS CATALOGED THE

HARDCOVER EDITION AS FOLLOWS:

ROBERTS, DAVID, DATE.

IN SEARCH OF THE OLD ONES ; EXPLORING

THE ANASAZI WORLD OF THE SOUTHWEST /

DAVID ROBERTS.

P. CM.

INCLUDES BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES AND INDEX.

1. PUEBLO INDIANSHISTORY.

2. PUEBLO INDIANSANTIQUITIES.

3. SOUTHWEST, NEWANTIQUITIES.

I. TITLE.

E99.P9R537 1996

979.004974DC20 95-46218

ISBN 0-684-81078-6

ISBN 0-684-83212-7 (PBK)

ISBN 13: 978-0-684-83212-8

eISBN 13: 978-1-439-12723-0

Contents

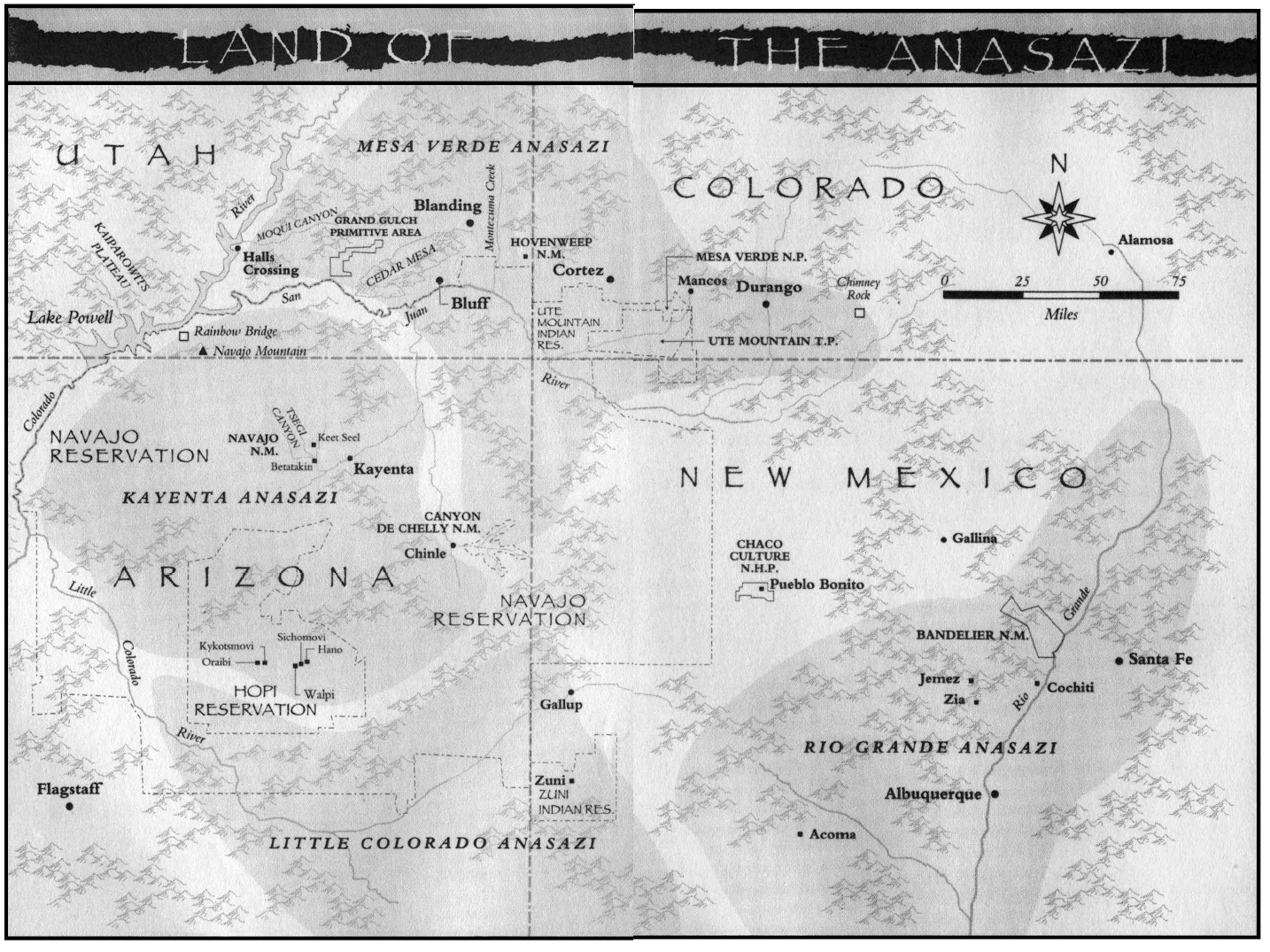

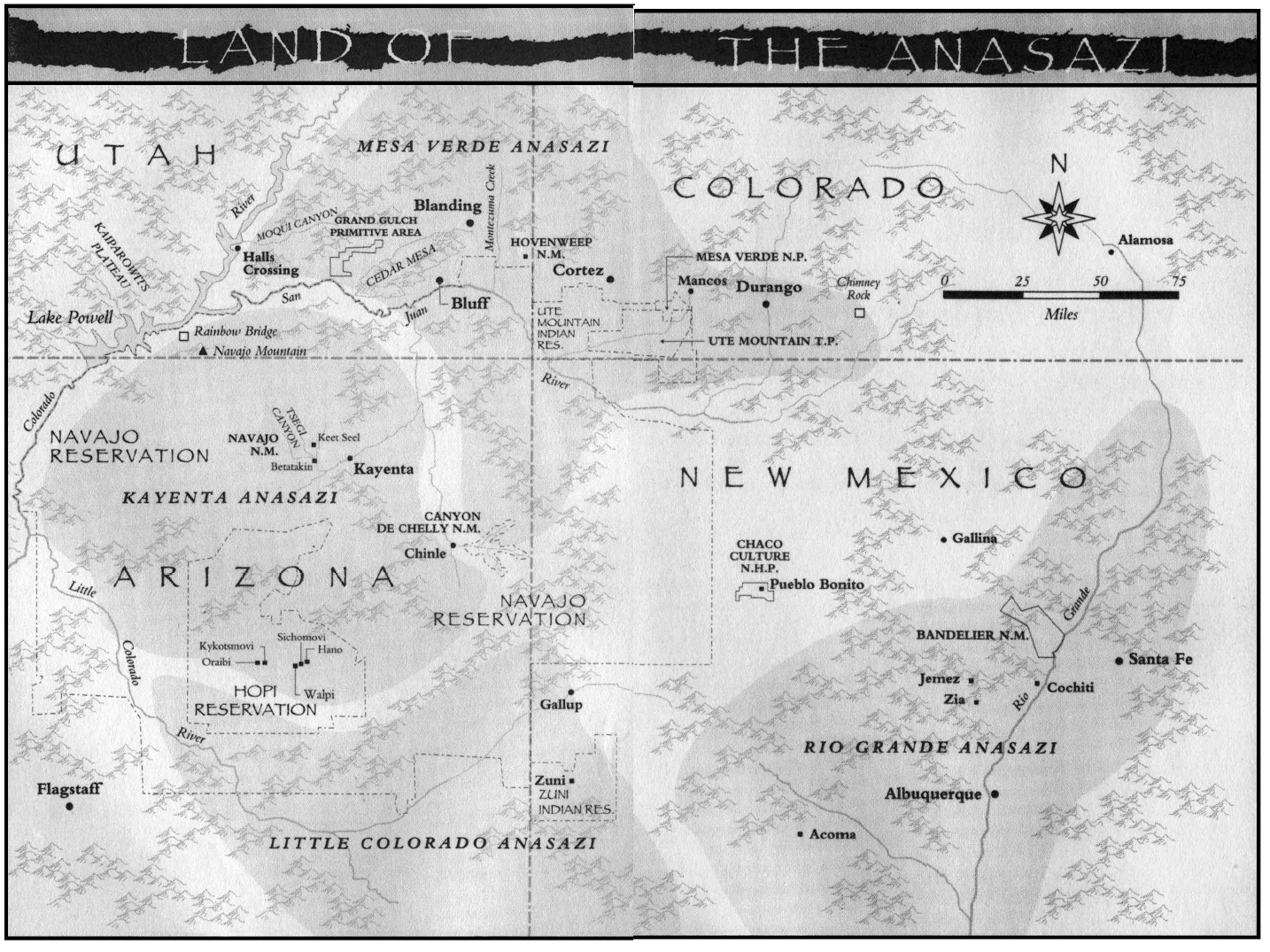

Land of the Anasazi

Authors Note

THE term Anasazia Navajo word meaning ancestral enemieshas been standard archaeological usage for the prehistoric people with whom this book deals since 1936, when it was proposed by Alfred V. Kidder. The term has always been offensive to the Hopi and other Pueblo Indians who are the descendants of the Anasazi. The word the Hopi use for their ancestorsHisatsinomis, however, different from the ancestral term in use at the Pueblo town of Zuni, which in turn is different from that used at the Pueblo town of Acoma, and so on.

In recent years, there has been a movement among younger archaeologists and some Pueblo people to substitute Ancestral Puebloans for Anasazi. This book resists that nomenclature on several grounds. Whatever its faults, Anasazi has been a well-defined archaeological term for almost sixty years (to distinguish that culture, for example, from the contemporary Hohokam to the south or Fremont to the north); Puebloan derives from the language of an oppressor who treated the indigenes of the Southwest far more brutally than the Navajo ever did; and, at book length, repeated again and again, Ancestral Puebloans is a cumbersome mouthful.

It may be germane to point out that no term embodies a more egregious misnaming than Columbuss Indians, yet Native Americans has yet to supplant iteven among American Indians themselves, who are still more likely to call themselves Indians than Native Americans.

Prologue

I WOKE at dawn, as alpenglow painted the sandstone wall behind my tent a lurid reddish orange. A film of ice had formed inside my water bottle; I shook it loose and took a cold drink. White rafts of cumulus clouds sailed across the sky out of the northwest, where the subarctic fronts came from. It would be windy up on the canyon rim.

I put on all the clothes I had and crawled out of the tent. The seat I had built of three flat stones was cold to the touch, so I laid my day pack across it before I sat down. The butane stove fired at the touch of a match, its dull roar erasing the silence of the canyon. On the stove I placed my smaller pot, filled the night before with water dipped from a bedrock pool down in the canyon bottom. The skim of ice on the surface melted in patches.

The date was October 29. It was my third day alone in the obscure canyon in southeastern Utah. During those forty-some hours, I had seen no one else. My voice felt rusty with disuse, for I am not the sort of solo vagabond who talks to himself for company.

Tiny bubbles were forming on the bottom of the pot. I spooned freeze-dried coffee into my metal cup and thought about the discoveries of the previous day. Joyous though my long prowl under the late-autumn sun was, I had been acutely aware all day of my vulnerability as I scrambled through a slickrock wilderness far from any trail. In the night I had wakened with a jolt at 2 A.M., then lain for two hours in my sleeping bag without a hint of drowsiness, watching through the transparent roof of my tent as the moon slid west above the canyon rim. Eventually the prickles of anxiety ebbed, and sleep filled my head.

Now I waited for the sun to rise in the V notch on the horizon, fifteen degrees south of east. I had chosen the campsite by compass, counting on that earliest possible sunrise, but now the sky abruptly darkened and a chilling rain began to fall. I hurried through breakfastcoffee, a packet of sugary instant oatmeal, dried apricots. Just as I zipped closed the tent and hoisted my day pack, the rain stopped and patches of blue poked through the streaming clouds.

The day before, from the rim across the canyon to the south, I had spotted a small ancient ruin tucked under the mesa top, visible from few vantage points. With binoculars I had invented an approach route, memorizing landmarks that would look a lot different when I was upon them. The ruin stood only a quarter mile east of my camp, four hundred feet above it. But I couldnt see it from camp, and I knew that a direct approach would be stymied by overhanging bands of rock.

I was off at 9 A.M. Eighty feet below camp, on the canyon floor, ice glazed the pothole pools. Here, thanks to the vagaries of the jutting skyline, the sun would not rise till about eleven, more than four hours after its rays found my tent. Most hikers in canyon country regard the ideal campsite as a sandy bottom bench under the limbs of some generous cottonwood, close to the trickling water. Not meand not the Anasazi, whose lives were woven tight into the wheeling circles of the sun.

On a bedrock of blue Halgaito shale, I hiked back upstream, retracing the path by which I had entered the canyon two days before. At the first north tributary, I veered right into a short, steep draw, then zigzagged upward among the ledges. The brown soil froze my footprints; I plucked sagebrush leaves, rubbed them, and breathed the bursting scentessence of the desert Southwest. Just below the rim, I had to climb a ten-foot wall. Be careful, this could be trouble, nagged the fussy worrier in my headthe one whose doubts had kept me awake in the night. Big deal, its easy, answered his cocky antagonist. A right hand jammed in a crack to pull on, a small hold high for the left foot, and I was up.

The wind hit me as I emerged on the rim, tearing my eyes. I pulled the hood of my jacket over my head and stood facing south, away from the wind. There across the canyon, silhouetted like a cardboard cutout beneath the sun, was the dizzy peninsula of stone that it had taken me the whole previous day to explore. Far to the east, dull brown in the low sun, heaved the humpbacked domes of the Comb Ridge. At that moment, was there another living person in the sweep of cosmos I surveyed?