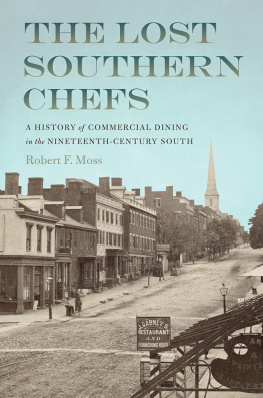

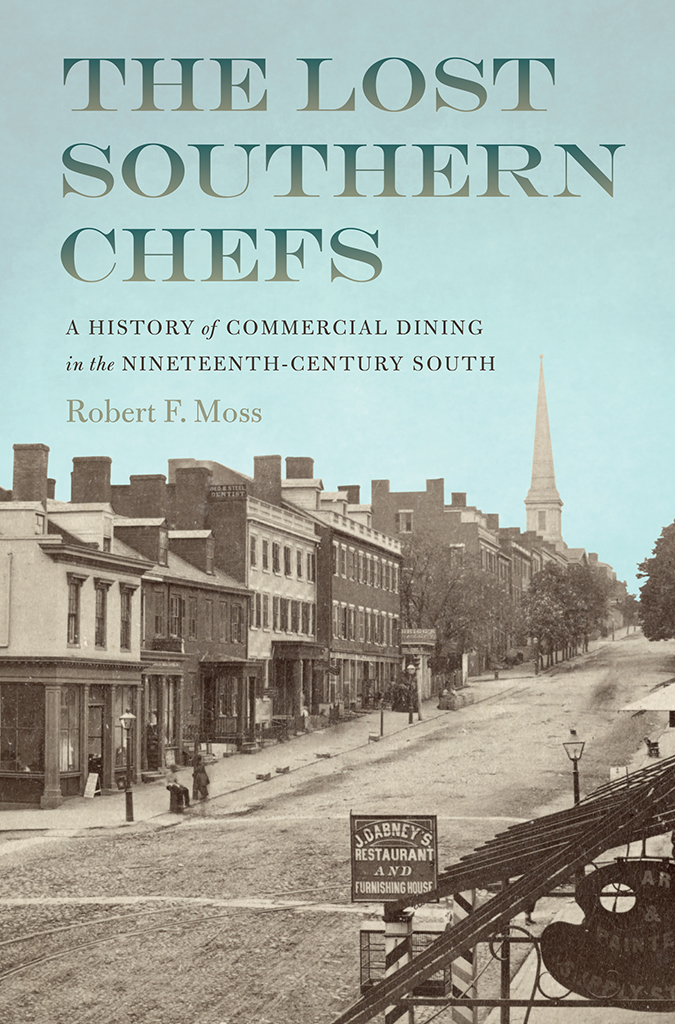

THE LOST SOUTHERN CHEFS

THE LOST SOUTHERN CHEFS

The Lost Southern Chefs

A HISTORY of COMMERCIAL DINING in the NINETEENTH-CENTURY SOUTH

Robert F. Moss

The University of Georgia Press

ATHENS

: Hancock's Restaurant, Washington, D.C.

(Library of Congreess Prints and Photographs Division)

2022 by the University of Georgia Press

Athens, Georgia 30602

www.ugapress.org

All rights reserved

Designed by Erin Kirk

Set in ITC New Baskerville

Printed and bound by Sheridan Books

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

Most University of Georgia Press titles are available from popular e-book vendors.

Printed in the United States of America

26 25 24 23 22 P 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Moss, Robert F., 1970, author.

Title: The lost Southern chefs : a history of commercial dining in the nineteenth-century South / Robert F. Moss.

Description: Athens : The University of Georgia Press, [2022] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021037127 | ISBN 9780820360850 (paperback) | ISBN 9780820360843 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Cooking, American--Southern style. | Cooking--Southern States.

Classification: LCC TX715.2.S68 M67 2022 | DDC 641.5975--dc22

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021037127

For Charlie

CONTENTS

Big thanks are due to Hannah Ayers and Lance Warren, the directors and producers of the documentary film The Hail-Storm: John Dabney in Virginia, from whom I learned of Wendell Dabneys manuscript autobiography and its detailed information about his fathers career in Richmond. Professor Ethan Kytle of California State University, Fresno, kindly shared with me a copy of Mrs. Francis Porchers letter about the Nat Fuller Feast, which he unearthed in the collections of the South Caroliniana Library and which solved a mystery that had long had me stumped.

As always, my wife, Jennifer, has been extremely supportive of my research and fairly tolerant of the many hours I spent holed up in my office instead of taking her to lunch.

Finally, this book wouldnt be possible without the scholarly work and kind assistance of Professor David Shields of the University of South Carolina. His pioneering work in this field is the reason why we even know the names of many of the figures who appear in this book. While working on his book The Culinarians, which was published in 2017, Shields compiled profiles of hundreds of once-famous and now-forgotten caterers and chefs from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. He generously shared his material with me while his book was still in manuscript form, including many profiles that ended up not making the cut for his finished volume. That material helped get the ball rolling for the research behind this book, providing some of the most crucial pieces of information of all: the names to look for. From there I was able to go back and retrace Shieldss tracks, starting with the sources he had identified and then digging deeper for additional newspaper articles, census records, city directory entries, and archival documents. In the process, I was able to flesh out the individual biographies, correct a number of ambiguities and red herrings, and begin to connect the many dots into my own interpretation of how commercial dining evolved in the American South.

But the story of southern restaurants and barsand the larger picture of southern cuisine in the nineteenth centuryis far too rich a field to be addressed in just one or two books. Following in the footsteps of Professor Shields, I hope I have beaten back a few more bushes and limbs and made the path clearer for others to follow. I anticipate that many more writers will continue to refine and correct the story as they find new dots of their own and connect them in ever more revealing ways. Weve only scratched the surface.

THE LOST SOUTHERN CHEFS

THE LOST SOUTHERN CHEFS

On an April evening in 2015, I was fortunate to be one of eighty guests invited to attend a remarkable celebratory dinner in Charleston, South Carolina. It was the Nat Fuller Feast, a commemoration of the 150th anniversary of a culinary event that, until just a few months before, I hadnt even known had happened.

I grew up in South Carolina. By 2015 I had been studying southern food culture for a good two decades, digging deep into the rich history of the regions foodwaysfirst barbecue, then the full southern culinary canon, and especially the long traditions of my adopted hometown of Charleston. How could it be that I had only recently heard the names of the once-famous caterers and cooks being honored that nightNat Fuller, Tom Tully, and Eliza Seymour Lee?

The dinners organizers had, of necessity, made a lot of educated guesses. They did not know the exact date of the original feast, just that it appeared to have occurred in April 1865, so they picked April 19 for the commemoration. Nor did they know the names of the guests or any of the dishes that were served. All they had to go on was a single line from a letter written by one Mrs. Francis J. Porcher, a wealthy white Charlestonian. Nat Fuller, the line read, a Negro caterer, provided munificently for a miscegenat dinner, at which blacks and whites sat on an equality and gave toasts and sang songs for Lincoln and Freedom. Mrs. Porcher, for the record, was not amused.

David Shields, an English professor turned food historian, and Kevin Mitchell, a chef and culinary instructor with a deep interest in southern food traditions, resorted to a sort of culinary forensics to stage the dinner. From scattered newspaper accounts and archival materials, they pieced together the repertoire of Nat Fuller as well as his protg Tom Tully and Fullers culinary mentor Eliza Seymour Lee to synthesize a likely bill of fare. Through historical triangulation they determined how the tables were likely to have been set and that the service likely would have been la Russe, with each course brought to the table sequentially, already individually plated. They even surmised what could have been said during the rounds of toasts that closed the meal. It was quite a feat of extrapolation, spinning a rich, compelling narrative from scant scraps of evidence. It wasnt until several years later that I realized exactly how scant that evidence was. In fact, the event that we were commemorating that night had never actually happenedor, at least, it hadnt happened in anything like the form in which it was reconstructed.

That such speculation and extrapolation were required reflected the state of research into southern professional cookery in 2015. Hundreds of books and thousands of articles on southern food had been published in the preceding decades, but the names of the great caterers of Charlestonand of Richmond, Louisville, and Washington, D.C.appeared nowhere in them. Those caterers are central characters in one of the great untold stories of the Souths cultural past, a story that is very different from the more familiar one about daily cooking on plantations or in family kitchens. Its not a story about fried chicken, grits, and cornbread, as delicious as those traditional southern dishes are. Its about a separate, parallel mode of dining, one that was public and commercial. That mode elevated southern cooking to the ranks of high art, and it earned fame and even fortunes for its most accomplished practitioners. And yet their names have been all but forgotten.

THE LOST SOUTHERN CHEFS

THE LOST SOUTHERN CHEFS