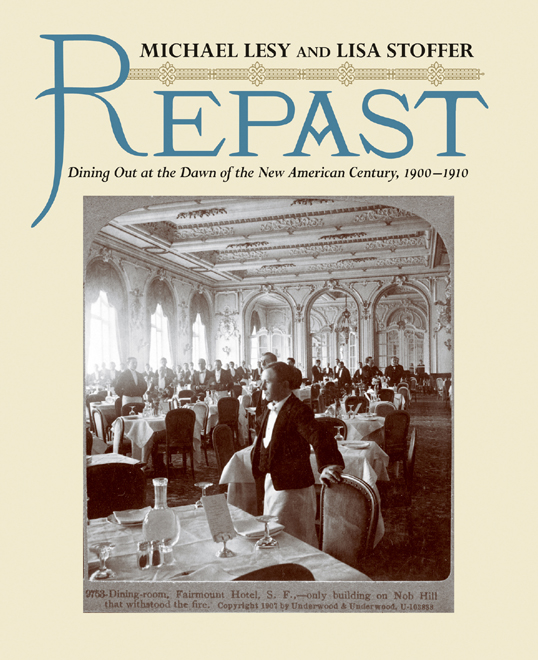

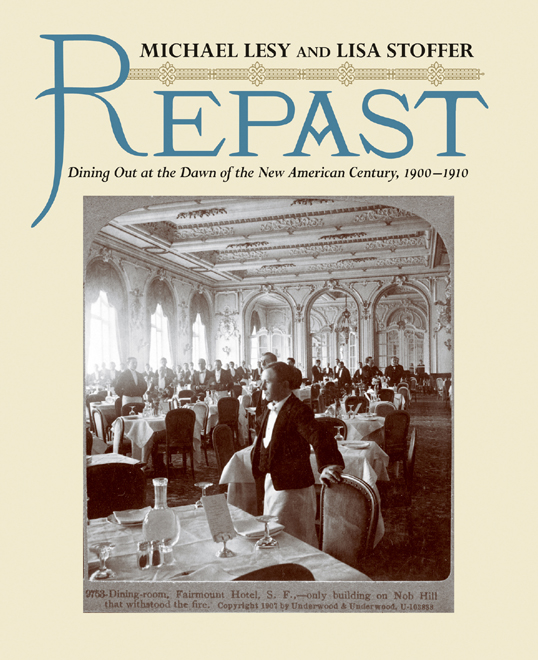

Daily menu, dinner specialties, Sportsmans Grill, The Breslin, New York [?], 1905

We are deeply grateful for the support and friendship of our editor, James Mairs, who championed and shepherded Repast from its earliest stages. Thanks to his assistant, Austin ODriscoll, who untangled the permissions that Repast required, the copy editor Don Kennison, who endured our many flagrant violations of the Chicago Manual of Style, and the designer, Laura Lindgren, who fitted together Repasts jigsaw puzzle of image and text. Thanks also to everyone at W. W. Norton who helped produce and market this book.

The quick and resourceful Allyson Vieira helped with research and word processing. Our agent, Marianne Merola of Brandt & Hochman, offered encouragement and critical advice. Thanks to Carl Brandt for connecting us with Marianne and for believing in this project from first to last.

Many friends, family members, and colleagues brainstormed with us, pointed the way to people and sources, and read drafts, including Michelle Aldredge, Elizabeth Barker, Ella Christopherson, Rene Fall, Ira Glass, Judy Goldman, John Helde, Elizabeth Kaplan, Roger King, Alex and Nadia Lesy, Greil Marcus, Bruce McClelland, Garth Meader, the late Mary Meader, James Miller, Jeff Sharlet, Steven Weisler, and Joel Wolfe. Hampshire Colleges Dean of Faculty office provided crucial summer faculty development funding; Hampshires librarian Jennifer Gunter King offered positive support as the book neared completion. The wonderful staff of the Robert Frost Library at Amherst College, especially Bryn Geffert, Missy Roser, Mike Kelly, and Stephen Heim, provided spot-on research advice and help navigating the interlibrary loan labyrinth. Megan Morey, Mary Ramsay, and Jeanne Weintraub of the Amherst College Advancement Office gave Lisa the flexibility and moral support that made it possible for her to take on this project while working full-time.

Finally, special thanks to Charlene and Bob Moran, for helping in innumerable ways, and to Isabel Masteika, who lived through the creation of this book with grace and good humor.

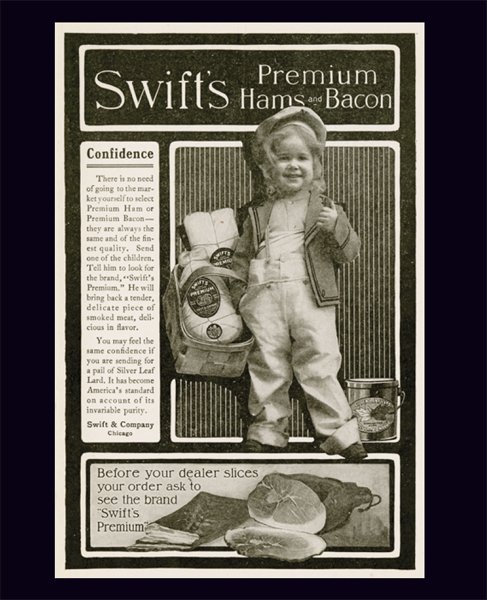

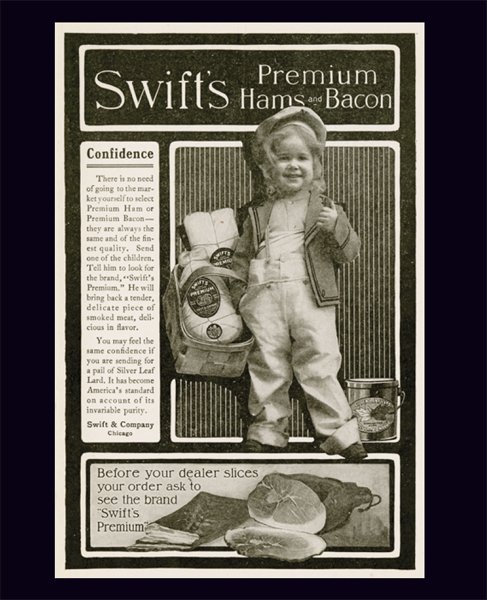

Harpers Magazine, 1901

The Spanish-American War began in April and ended in August 1898. In those four months, ten times more enlisted men and officers died from disease and malnutrition than from combat. A splendid little war was the way patricians such as John Hay, high and dry and well fed in his American ambassadors residence in London, chose to think about what happened. In the huge, filthy army camps in Virginia and Tennessee where most of the 200,000 men whod volunteered spent the war, and in the tall grass, heat, and mud outside Santiago, Cuba, inadequate hygiene, inedible food, and inept medical care came close to producing a catastrophe.

Typhoid fever swept through the volunteers held in reserve in the United States. One month after 15,000 American troops took San Juan Hill, malaria had disabled 75 percent of them. Rancid food, unpalatable and indigestible, worsened their suffering.

On the first of August, 1898, ten generals and colonels, all line officers in Cuba, sent an alarming letter to their commander: We, the undersigned... are of the unanimous opinion that this army must at once be taken out of the island of Cuba and be sent to some point on the northern sea coast of the United States... the army is disabled by malarial fever to such an extent that its efficiency is destroyed... it is in the position to be practically entirely destroyed by the epidemic of yellow fever sure to come in the future... this army must be moved now or it will perish.

On August 4, copies or paraphrases of the officers letter appeared in the morning editions of nearly every major newspaper in America. Teddy Roosevelt had been one of the colonels whod signed the original. As shouts of alarm and accusation spread across the country and crashed into the White House, Roosevelt offered a few additional comments of his own. The whole command, he said, is so weakened and shattered as to be ripe for dying like rotten sheep.

President McKinleys White House found itself in an awkward position. Peace negotiations with Spain were well under way. Spains naval forces had been destroyed, but an American withdrawal from Cuba might make Spain less willing to surrender. Worse yet, American midterm elections were in the offing. A panic-stricken evacuation of men some of whom might be carrying yellow fever home with them wouldnt help the Republican Party.

Fortunately, Spain capitulated within weeks of the issuing of the letter. Just as fortunately, so the story goes, McKinley received a letter from the mother of a soldier. We are living under a generous government, wrote the lady, with a good, kind man at its head, willing to give the Army the best possible, and yet thieving corporations will give the boys the worst. By the worst the lady meant the so-called food her boy had been given to eat.

The president did what any good, kind man would have done: he appointed a special commission to investigate the way the War Department had fed and cared for every mothers son who had fought to avenge the Maine.

The White House had a difficult time finding an army general willing to conduct a dog and pony show for the Republican Party. Eventually, McKinley found a retired general named Dodge who was not only a Republican and a millionaire but a friend of the secretary of war. Neither the White House nor its General Dodge anticipated the embalmed beef scandal that was about to break.

The man who hauled into public all the stinking meat that the army had fed its soldiers was none other than the armys own commanding general, Nelson Miles. Miles was a Medal of Honor winner and Civil War officer whod gone west to fight Indians. In 1894 the government had sent 12,000 men under his command to break the Pullman strike in Chicago.

Miles disliked army bureaucrats and staff officers a little less than he disliked Indians. As to beef, as long as it came fresh on the hoof he was glad to eat it.

Miles had begun to hear reports about bad beef in June 1898, when hed inspected troops waiting in Tampa and Jacksonville to be sent to Cuba and Puerto Rico. The refrigerated beef killed and quartered in Chicago by Swift & Company, then sent to Tampa in iced refrigerator cars (ammonia refrigeration didnt come into use until two years later) smelled as if it had been injected with chemicals to keep it from spoiling. The general and one of his medical officers thought the stuff smelled as if it had been embalmed. Embalmed or not, some of the meat still went bad and had to be tossed into the ocean. As to the canned roast beef: it ranged from the lowest-quality scrap and gristle to the lowest-quality stew meat. Millions of cans of it had been sold to the army by the Chicago packinghouse Libby, McNeill & Libby.

In July, Miles himself directed the invasion of Puerto Rico. Even though there was plenty of cattle on the island and plenty of fresh beef for sale (at half the price American cattle growers charged the army) Miless men were forced to eat the rank, refrigerated beef theyd brought with them or the gray, gristly stuff in cans. Miles began to believe that the chemicals used in treating the beef were responsible for the great sickness in the American army.

In September, Miles ordered every regimental commander whod served in Cuba or Puerto Rico to write evaluations of the canned beef rations they and their men had been issued. He directed his officers to submit their evaluations to the War Department. The officers described opening cans of beef with pieces of rope and dead maggots in them. They described cans that, once opened, gave off odors so foul that, according to the

Next page